What Your Brain Does When You're Doing Nothing

- Published9 Jan 2019

- Reviewed9 Jan 2019

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

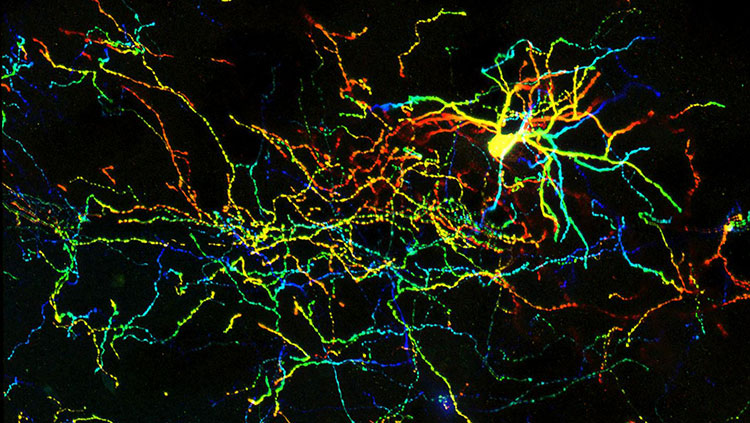

Your brain never turns off. Even when you give your mental muscles a break and just stare off into space, there’s still a lot going on between your ears. Neuroscientist Marcus Raichle explains what your brain is doing when you’re doing nothing.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

Screen Text: Does your brain ever really shut off?

MR: No. Emphatically not. No. You know you still hear this, I’m only using part of my brain, or I activated my brain, or I turned it on, all of which implies that it goes into some sort of dormant state that if I were to look in, it would just be a true black box. Nothing could be further from the truth. I mean, the first thing to know is that among the organs of the body, it’s continuously the most expensive.

Now the muscles can have bursts of energy use when you’re running or walking, but they can go to zero. The brain kind of oscillates somewhere between 95 percent and 100 percent most of the time. We’ve known this for a long time, it goes back to studies that were done right after the Second World War where the whole brain metabolism was measured. The amount of oxygen consumed, which tells us how much energy is used, it became blatantly obvious that it was using a lot. It’s only two percent of the body’s weight and it’s 20 percent of the cost of running the body.

Now one of the clever things we learned to do when imaging was developed was to be able to compare doing something to not doing something. We got rather clever of being able to take your brain and my brain and with computers make them sit one on top of the other, so we could add them all up.

We could compare you sitting there and moving your hand, or looking at a flashing light, or something, and we looked at the difference. When you looked at many of those images and now with fMRI, you do much of the same thing, you see a spot lighting up here, and a spot lighting up here, and depending on what the color scale is you use, my gosh it looks like this thing just lit up, and there’s nothing in the background. Well the thing is, you’ve just subtracted the background. If you actually get in there and measure the amount of change, it’s inside 10 percent.

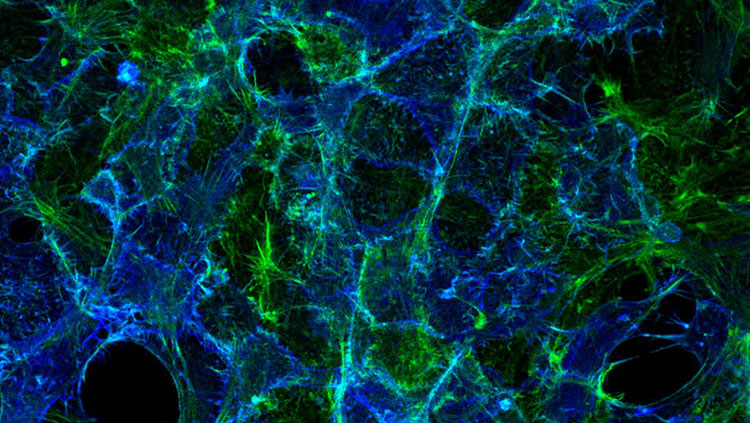

Screen Text: The parts of the brain that come “online” when you’re doing nothing are called the Default Mode Network.

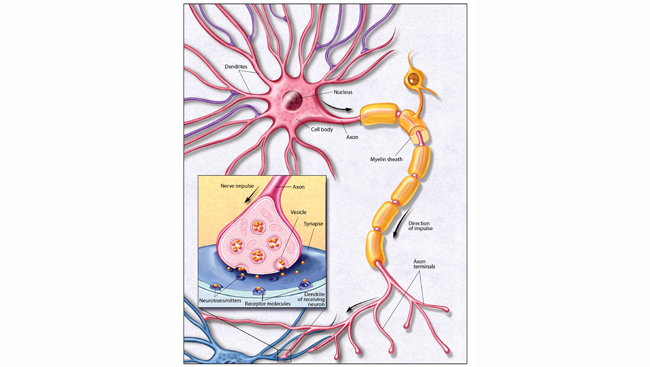

MR: What you can learn from this is that all of the large-scale systems — your somatomotor system, your dorsal and ventral attention system, your visual system, your auditory system, the basal ganglia — they’re all conspiring in this sort of thing. In such a way that you can lay out a map, the basic functional structure of a human brain, or a nonhuman primate, or a cat, or a rat, or a mouse, you can find the default mode network all the way down to a mouse now, in one form, in an abbreviated form, but the same general thing is there.

Screen Text: What is my brain doing when I’m doing nothing?

MR: My usual answer to a question in one sentence, what is the brain doing, it’s in the prediction business. It is building a model of the world and it applies that model to understanding what we see, and hear, and touch. It’s for sure that. The other side of that coin is that as Vernon MountCastle said in a fabulous lecture he gave before he died at Hopkins, that our view of the world is an illusion. That most of what we see in the world, whether it’s you and these screens, and the gentleman behind the camera here, is being constructed by my brain because of the very impoverished data that actually gets through my eyes and into my visual cortex, it is a fraction of what’s out there. It’s so counterintuitive. It’s just as if like, “Oh this can’t be true.” But it is. How does this work? Well, the brain therefore has to be in the prediction business, and of course that makes complete sense.

As I, and James, and various other people, have talked about, how in the devil would you get out of bed and get dressed in the morning if you hadn’t already programmed this? I mean, really? You don’t think as you’re sitting there, and if you write or you do whatever you do, you’re not thinking about the detailed muscles and how you’re moving and all this stuff, of course not. It’s all been laid out.

Screen Text: What are you hoping to find in your research into the default mode network?

MR: I mean I think a lot about what its role is. I think the bigger picture that has emerged out of it is to try to better understand the organization of the brain, that is ongoing, intrinsic, non-conscious, which is something we haven’t talked about, but most of what it’s doing is not conscious. Getting a better understanding of how that is organized. This involves not only at the very large-scale of a neuroimaging device, but electro-physiologically, and metabolically, and all of these sorts of things. How does this come about? How does a piece of biology get itself organized?