According to news sources, on Friday morning, December 14th 2012, Adam Lanza walked into Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, and slaughtered 26 people – 20 precious children (6 and 7 year olds) and 6 heroic adults who worked at the school. Mr. Lanza was dressed in black battle fatigues and a military vest, according to a law enforcement source. So he had apparently put some thought into his actions.

In the end the only thing that stopped Lanza was himself - he was reportedly found dead in a classroom with a .223-caliber Bushmaster rifle and two pistols, a Glock and a Sig Sauer, within reach (warning: the links I provide here to the rapid firing of these semi-automatic firearms are chilling).

Early reports from some sources suggested that Lanza had been diagnosed with Asperger’s, a disorder that is generally classified on the mild end of the autistic spectrum: “A law enforcement official, speaking on condition of anonymity because the person was not authorized to discuss the unfolding investigation, said Lanza had been diagnosed with Asperger's.”

We don’t yet know whether this is a confirmed diagnosis from a professional, or only someone’s idea of his condition. But what we do know is that Asperger’s alone is not predisposing to violence. Asperger’s is characterized by social and communication impairments and restricted and repetitive behavior. The diagnostic criteria do not include violent acts toward themselves, or others.

Next, reports that the suspect had an unusual pain threshold, so much so that one of the advisers of the Newtown high school technology club had the job of looking after him to keep him from harming himself. This was extended to include “psychological” pain, suggesting that the suspect lacked empathy.

It’s easy to be drawn to these sorts of reports, and each feeds into a kind of confirmation bias – the data points that align with our expectations of someone capable of killing children with multiple gunshots are retained, while those that do not are cast aside.

It’s a ready-made explanation of the inexplicable - and a natural consequence of seeking meaning in this horrific act.

Pinning this to Asperger’s, or something else, is not only wrong on the face of it, it also stigmatizes those with these conditions – and an even bigger danger is that it distracts us from the real problem because we have identified the “cause” of this tragedy. After all, “guns don’t kill people, people kill people”, right?

So let’s not mince words. Killing 20 children is the deranged act of a profoundly impaired mind, and it may be weeks or months, if ever, before we know the full nature of the impairment. While it is useful to search for the causes of such an act (and we should continue to do so), eventually we will be led past the threshold of logic and down a rabbit hole of mental illness. If we lose focus by entertaining unfounded hypotheses about a deranged person’s mental process, about which we can do nothing, we risk distraction from actions worthy of this tragedy.

The armchair remedies are also flying. To some, our flawed approach to mental health diagnosis and treatment is the problem, and it is certainly less than perfect. Still others claim a better system of background checks for the purchase of firearms should be in place, and perhaps there should be, but better checks would not have prevented this tragedy - because the guns apparently belonged to Lanza’s mother.

It’s going to take a while for the full picture of what happened at Sandy Hook, and why, to develop. But we already have far too many snapshots of these kinds of killings, enough to know the common denominator – semiautomatic weapons, and lots of bullets.

At Sandy Hook Elementary, it was enough bullets for the shooter to blast his way through security measures that had been put into place.

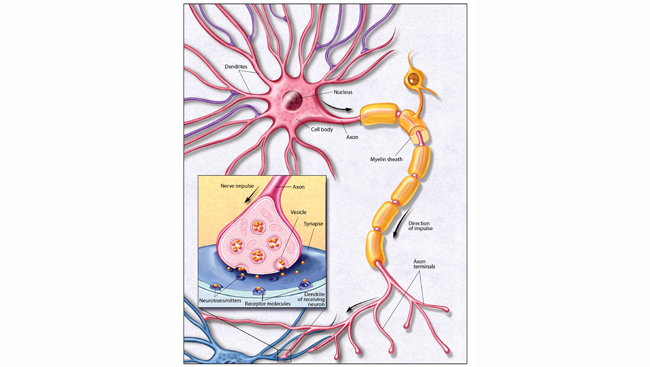

In the memory of these children, we must at least do something about that: because we will continue to have fractured minds in our society. Broken brains, unlike broken limbs, are not always easy to spot, and many will continue to elude proper diagnosis and treatment. Those who tragically fall through the cracks must be denied easy access to military-level firepower.

And to those who claim that the solution is to arm everyone, I ask whether it is reasonable to have a teacher or principal in elementary education be “at ready” for a situation like this, which even though it is alarmingly common is also very rare when distributed across the populace?

In TV shows, movies and video games the hero steels themselves or otherwise gets ready to meet force with force (and in video games, there are multiple "do overs"). But any police officer can probably tell you that the unexpected threat is far more common and deadly than the anticipated one. To expect our teachers to pack heat in the classroom is delusional.

So yes, Mr. President, let us weep together for the children of Sandy Hook. But let us also resolve to act with common sense and the tools at our disposal to reduce the chance that it will happen again. We can do this.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN