Are Migraine and Seizure Related?

- Published2 Aug 2018

- Reviewed2 Aug 2018

- Author Jennifer Michalowski

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

On the surface, migraines and epileptic seizures look nothing alike. Hyperactivity in brain circuits triggers the characteristic symptoms of seizures, like convulsions and loss of consciousness. A typical migraine, on the other hand, involves a throbbing headache, nausea, and sensitivity to light and sound.

Yet, despite their distinct symptoms, scientists like Michael Rogawski think migraine attacks and epileptic seizures may originate from similar disruptions in brain activity. Rogawski, a professor of neurology and pharmacology at the University of California, Davis, studies these similarities and what they might mean for treating the two conditions.

Is there a relationship between migraines and seizures?

One important commonality is that both migraine and epilepsy are what we call episodic disorders, meaning patients are generally normal, and then every so often they have spontaneous attacks. We don’t usually know precisely what has triggered a particular seizure or migraine attack, but both have trigger factors that can increase the likelihood of an attack.

Migraines and seizures both involve abnormal electrical activity in the brain. In many episodic disorders, abnormal brain activity is caused by alterations to ion channels — pores in cell membranes that permit the flow of charged particles into and out of neurons and drive electrical signaling. This is clearly the case for certain epilepsies, which are associated with mutations in any of several different ion channels that control signaling in the brain. We don’t know the underlying cause of the vast majority of migraine cases, but in some very severe cases, we have found defects in ion channels and related proteins.

Additionally, there are two or three epilepsy drugs that are actually effective in the treatment of migraine. One, topiramate, is used more widely for migraine even though it was originally developed for epilepsy. Not every epilepsy drug is useful in treating migraine, so there is clearly a big difference between the two conditions, but there are also some remarkable similarities.

Are there similarities in what happens in the brain during a migraine and what happens during a seizure?

The fundamental event in an epileptic seizure is an abnormal, hypersynchronous discharge of neurons that we can see by attaching electrodes to a patient’s scalp for an EEG (electroencephalography). That is not the case for migraine.

There is very strong support for the idea that migraines — at least migraines with aura — are caused by a phenomenon called cortical spreading depression. Normally, nerve cells exist at a very hyperpolarized level, meaning the electric potential inside the cell is more negative than it is outside the cell. When excitatory signals come into neurons, the membrane potential depolarizes or becomes more positive. That activates action potentials in the neurons, and that’s how signaling in the brain works. During cortical spreading depression, a wave of dramatic depolarization moves along the surface of the brain’s cortex and the affected brain tissue is, for a brief period, so depolarized that it can’t be depolarized anymore and can’t generate action potentials. This cortical spreading depression recovers, but we think it’s the trigger for a migraine. It stimulates the brain to release mediators that activate pain-sensing nerves in the covering of the brain. Then the migraine headache takes over and can last for up to three days.

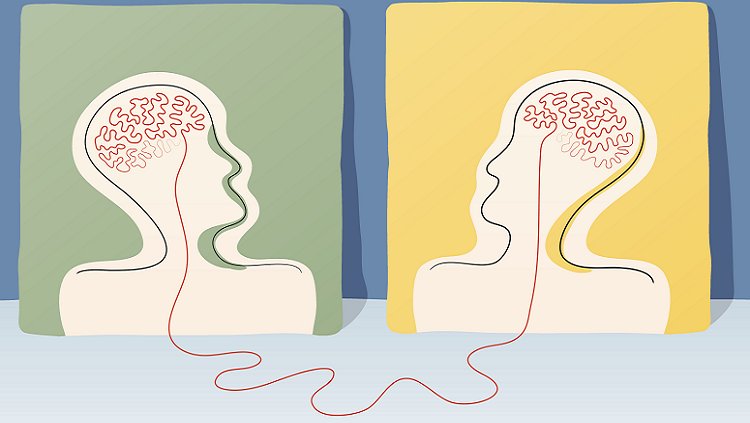

So in migraine, most of what you’re seeing is a temporary silencing of the brain tissue. But, before the tissue is silenced, it’s highly active. At the leading edge of a cortical spreading depression wave, we see hyperexcitability resembling what occurs in an epileptic seizure. What I’ve proposed is that after this initial hyperexcitability, in epilepsy, you go down a pathway where you get lots of synchronized firing, and in migraine you go down a pathway that leads to cortical spreading depression. Why migraine occurs in some situations and epilepsy in others, we don’t know.

Could exploring these commonalities help us develop better treatments for the two conditions?

I believe that would be useful. There have been some major advances in migraine therapy — recently and about 20 years ago. These breakthroughs haven’t led to useful treatments for epilepsy, because they act on the last stage of the migraine — activation of the pain system. If we investigate and maybe prove that there is a fundamental commonality in the initiation of these attacks, we might be able to develop more drugs that work on both conditions.

This question was answered by Michael Rogawski as told to Jennifer Michalowski for BrainFacts.org.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that epilepsy results from unsynchronized firing of neurons. Epilepsy results from an abundance of synchronized firing. This version has been corrected.

BrainFacts.org welcomes all your brain-related questions.

Every month, we choose one reader question and get an answer from a top neuroscientist. Always been curious about something?

Please submit your question by filling out this form.