Didn’t sleep well last night? Your immune system may be in overdrive today, starting or continuing a cascade of stressors that could spell ill for your body and brain.

Janice Kiecolt-Glaser stepped through several studies and reviews of research on immune reactions to stress during the forum “Stressing About Stress – What Our Minds and Bodies are Going Through and Ways to Cope” at the American Academy for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) in Washington, DC, on Thursday. “If you didn’t sleep, if you had a tired night, your IL-6 levels are higher today,” said Janice Kiecolt-Glaser of Ohio State University. IL-6 (Interleukin 6) triggers inflammatory and auto-immune processes that protect the body, but too much response has been linked to such diseases as diabetes, atherosclerosis, lupus, arthritis, and anxiety and depression.

“If you say you’re really busy and you enjoy it – that’s not stress. If you say you’re busy and feel overloaded – that’s stress,” she said. Characteristics that can build into stressors are events and situations that people can’t control or predict; that they don’t desire, including loss; and that are chronic. “A whole variety of endocrine changes take place in response to stress,” she said; these changes contribute to illnesses, which can feed back into the loop as more stress.

Kiecolt-Glaser described two “critical periods” when stress response seems to have more of an effect: Infancy and childhood, when immune and other body systems are developing, and aging (ages 60-75). For the elders, she said, who might consider their glass of life already half-empty, think of the glass as half-full: “You don’t want to spill any more out of it. You don’t want stress to take any away.”

To study effects of stress among older people, she has done much research with people caring for a family member with dementia; such care can be considered a chronic stressor. For most caregivers, outside activities fall by the wayside as they focus on the needs of another; for many, important social networks and friendships also fade.

Caregivers took an average of 24 percent longer than well-matched controls to heal the same small standardized wounds, she said. Caregivers’ antibody responses to influenza vaccines were substantially poorer than well-matched non-caregivers, and caregivers have shorter telomeres (protective tips of chromosomes) than controls.

Kiecolt-Glaser and colleagues have found similar troubles with non-chronic stressors as well, comparing healing time in students while on holiday vs. the same students during exam week. Guess when wounds took longer to heal and when immune reactions to vaccines were less robust? “When you go to get your annual vaccine, which I want you to do, think about your levels of stress,” she told us. [See more on possible immune effects on the brain in our fall BrainWork story, "The Brain Inflamed"]

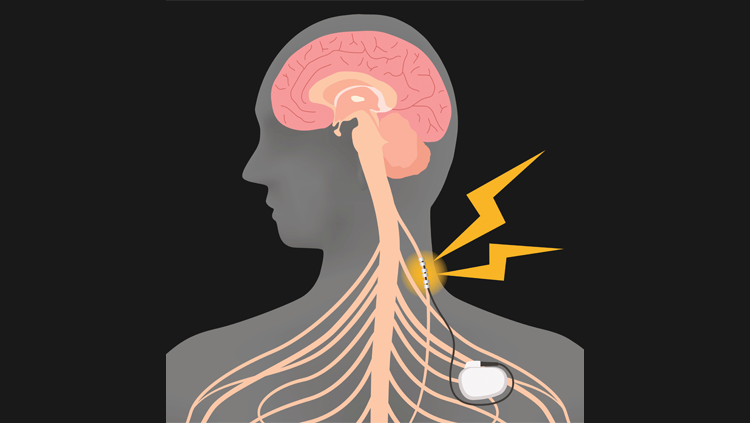

How can we counteract effects of stress? For people whose stress includes depression or anxiety, antidepressants can help break some of the immune-crash cycle. For all, exercise — physical activity — can ease effects, she said.

According to the National Health Interview Survey from 2007, 40% of adults use some form of complementary or alternative medicine. Meditation, massage, and yoga were the top three used in 2007; early results from the 2012 survey (still in analysis) suggest that yoga is now No. 1, Shurtleff said. Other approaches that have some support include meditation, yoga, and other practices, said David Shurtleff, deputy director of the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health. The Center rigorously investigates such approaches. Half its research budget is spent on research on “natural products,” and they’re looking more into probiotics, mind-body practices, and non-pharmalogical interventions.

“Active re-learning of the emotional response to stress can lead to beneficial changes in brain structure,” he said, citing a Boston study in which non-meditating people followed a mindfulness-based stress-reduction program for eight weeks. They described larger decreases in perceived stress, and researchers saw a reduction in gray matter volume in the amygdala, a brain area associated with emotional reactions (and other functions).

“Pain also modulates our emotions and cognition — and cognition and emotion can influence how we feel pain,” he said. “We need to get a better understanding of how it works” so we can treat people more successfully. NCCAM is working with the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs, investigating multiple methods to help veterans better manage pain and PTSD.

Of natural products, people are using a lot of omega-3, while use of echinacea, ginko biloba, and St. Johns’ Wort are fading. Those decreases are good news, Shurtleff said, since NCCAM research has found them ineffective or harmful when combined with other drugs, in most cases.

The session was part of the Neuroscience and Society series, supported by AAAS and the Dana Foundation. A video of the session is on our YouTube site. The next event, “Illusion and the Brain,” takes place just days before Halloween, Oct. 28.

— Nicky Penttila

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

The Dana Foundation is a private philanthropic organization that supports brain research through grants and educates the public about the successes and potential of brain research.