Do People With Dyslexia Read and Write Backwards?

- Published22 Aug 2018

- Reviewed22 Aug 2018

- Author Alexis Wnuk

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Dyslexia is an unexpected difficulty in learning to read despite normal intelligence and vision and access to good instruction. Today, scientists generally agree that people with dyslexia struggle to read because they have trouble linking the shapes of printed letters with the sounds of spoken language — not because they have problems with visual perception or memory.

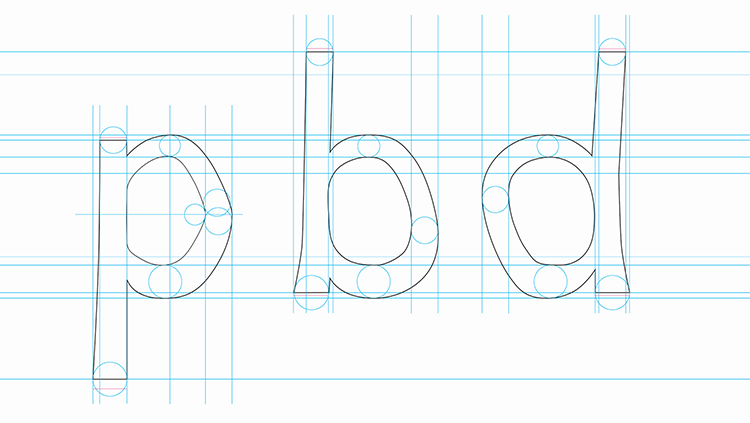

In the 1920s, neuropathologist Samuel Orton observed that children with reading difficulties struggled to differentiate between similarly-shaped letters — b and d, for instance — and often read words from right to left — ton became not. Some of the children could read more easily when looking at the mirror image of the text. He coined the term strephosymbolia, meaning “twisted symbols,” to describe what he thought was the primary deficit of reading disability.

Medical terms like that “are hard to get rid of,” says Guinevere Eden, a neuroscientist who studies dyslexia and learning disorders. The Georgetown University professor credits the term for the pervasive misconception that people with dyslexia read and write backwards.

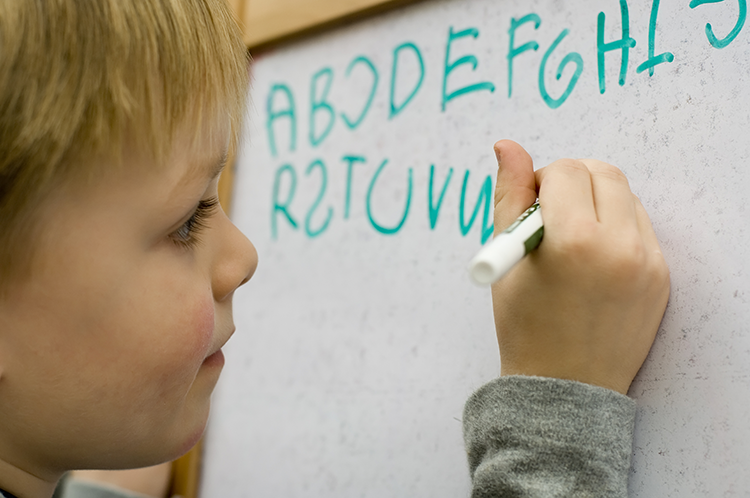

The behaviors Orton first described in the ‘20s are not unique to children with dyslexia: Almost all children reverse letters when they’re first learning to read and write. “It’s so common that it’s a poor way to distinguish typical from atypical reading development,” says John Gabrieli, a neuroscientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Neuroscientists speculate that this is so common because when it comes to recognizing shapes and objects, our brains don’t seem to care whether that object is reversed or rotated: A dog is a dog, whether it’s facing left or right. “Our visual system is designed to be flexible,” Eden says. “But that’s not so good when it comes to reading,” where reversing a letter changes its meaning. Learning to read involves overriding our wiring and retraining our brains to care about letter orientation.

Through years of learning and practice, children eventually stop reversing letters. Some children with dyslexia might not grow out of it as quickly because their reading skills don’t advance.

For dyslexic children, the enduring misconception about the disorder could delay appropriate intervention. “People might inadvertently think that that’s the way to help a child who’s struggling to read, that if you can just get them to focus on getting the letters oriented correctly that they would make major progress in their reading,” Gabrieli says. Effective interventions involve intensive phonics instruction to help children identify and manipulate the sounds of language — like practicing rhyming — and connect them to letters.

It can also be a potential source of bullying and embarrassment, says Elizabeth Norton, a neuroscientist at Northwestern University. When she was a teacher for high school students with dyslexia, she says kids worried that their peers wouldn’t understand the challenges they faced. “The idea that dyslexia is just the simple thing of making reversals makes it seem like [it would be easy to outgrow]," she says. “Their peers don’t understand that this is a much more complex problem that you’re born with, it’s not going away on its own, and it’s not that the student isn’t smart or isn’t trying hard.”

Dyslexia is a lifelong condition, but early intervention to address the core difficulties can substantially improve children’s reading ability, Gabrieli says.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Blackburne, L. K., Eddy, M. D., Kalra, P., Yee, D., Sinha, P., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2014). Neural Correlates of Letter Reversal in Children and Adults. PLoS ONE, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098386

Dehaene, S., Nakamura, K., Jobert, A., Kuroki, C., Ogawa, S., & Cohen, L. (2010). Why do children make mirror errors in reading? Neural correlates of mirror invariance in the visual word form area. NeuroImage, 49(2), 1837–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.024

Lachmann, T., & Geyer, T. (2003). Reversals in reading – Is the case really closed? A critical review and conclusions. Psychology Science, 45, 50–72. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Lachmann/publication/229018917_Reversals_in_reading_-_Is_the_case_really_closed_A_critical_review_and_conclusions/links/09e4150befb3038ec5000000/Reversals-in-reading-Is-the-case-really-closed-A-critical-review-and-conclusions.pdf

Orton, S. T. (1925). WORD-BLINDNESS IN SCHOOL CHILDREN. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry, 14(5), 581–615. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurpsyc.1925.02200170002001

What to Read Next

Also In Childhood Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org