Laminins Lay Down Tracks for Future Nerves

- Published18 Sep 2019

- Author Charlie Wood

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

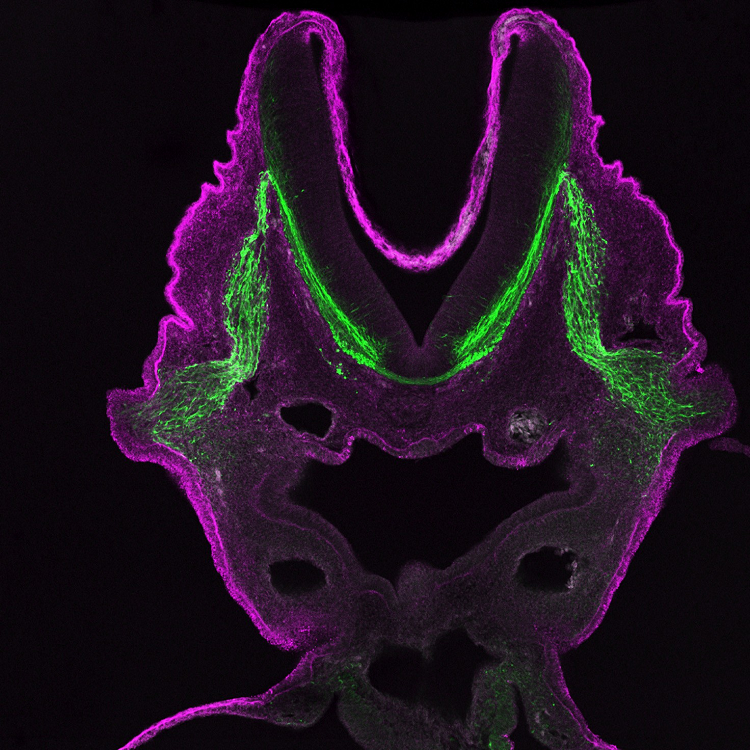

They may look like horns, but the mauve peaks in this developing embryo will fuse into a tube before eventually growing into a spinal cord and brain. As these organs mature, they’ll need a complex network of informants to keep them up to date on the goings on of the body through signals of heat and pain, as well as to execute their orders. The forerunners of these nerves, shining green, crawl out from the tube’s base, feeling their way toward the periphery with the help of proteins called laminins, highlighted here in purple.

Laminins form part of the innermost layer of the sac that holds your brain as well as an outer layer of the blood vessels that crisscross it. In a sense, laminins represent the boundary between the nervous system and the outside world. As such, they’re a good way for growing axons to know they’ve reached the edge of the map. Neuroscientists once thought laminins might guide axons by touch, forming a surface for them to stick to. More recently, however, researchers have shown that laminins may call out to axons with chemical messengers that help them find their way, although details remain rough.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Bonner, J., & O’Connor, T. P. (2001). The Permissive Cue Laminin Is Essential for Growth Cone Turning in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience, 21(24), 9782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09782.2001

Jucker, M., Tian, M., & Ingram, D. K. (1996). Laminins in the adult and aged brain. Molecular and Chemical Neuropathology, 28(1–3), 209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02815224

Rogers, S. L., Edson, K. J., Letourneau, P. C., & McLoon, S. C. (1986). Distribution of laminin in the developing peripheral nervous system of the chick. Developmental Biology, 113(2), 429–435. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90177-6

Also In Genes & Molecules

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org