Combating Zika Virus

- Published11 Aug 2016

- Reviewed11 Aug 2016

- Author Hilary Gerstein

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

After a jump in the number of birth defects in South America, governments and scientists are focusing on combating the suspected culprit — Zika virus.

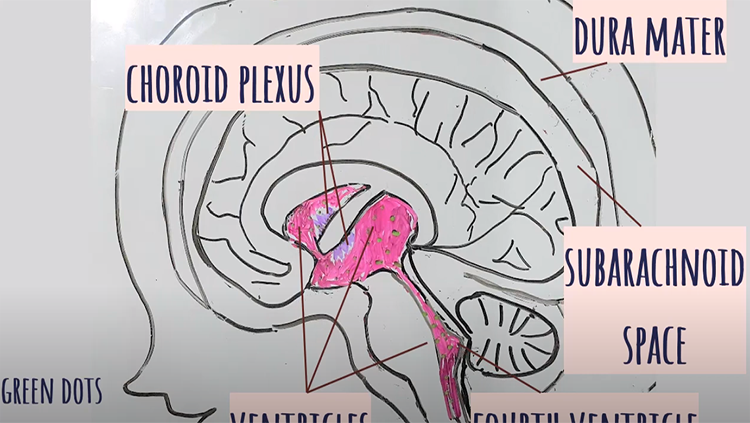

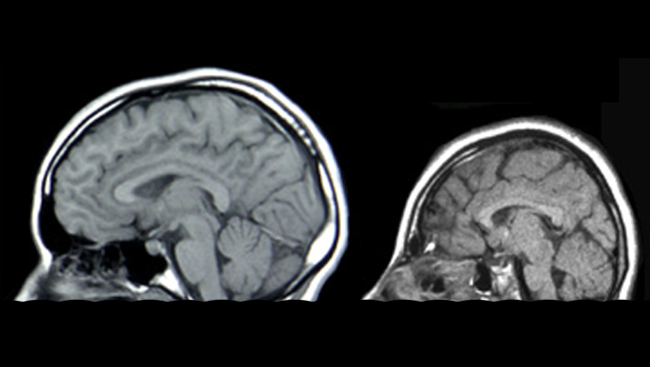

The virus gained worldwide attention after it was linked to a surge in the number of babies born with microcephaly, a rare and serious birth defect resulting in an abnormally small and deformed brain. In the race to develop a vaccine against the virus, research using nonhuman primate animal models is providing critical insights into how the virus can affect the brain.

First identified in Africa 1947, Zika virus is transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes, most commonly the Aedes aegypti species, which lives in tropical and sub-tropical climates. Pregnant women can also pass the virus to the fetus and, in a few instances, the virus has spread through sexual contact. Typical symptoms include fever, rash, joint pain, and pink eye. However, up to 80 percent of healthy adults infected with Zika show mild or no symptoms, and many do not realize they are infected.

In rare cases, the virus, which reached epidemic proportions in South America in 2015-2016, can cause Guillain-Barré syndrome, a serious but usually temporary progressive paralysis in adults. In pregnant women, however, the consequences of Zika infection are severe, as it can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, and infants born with microcephaly and other serious brain defects.

To understand how the virus affects the nervous system and how it can compromise fetal brain development, researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis developed a mouse model of Zika virus infection. They found that, in pregnant mice, Zika infection damaged the placenta and impaired blood flow to the fetus, hampering growth and development. However, the researchers did not observe microcephaly in the offspring, and they speculated this may be due to differences in the way mouse and human brains develop.

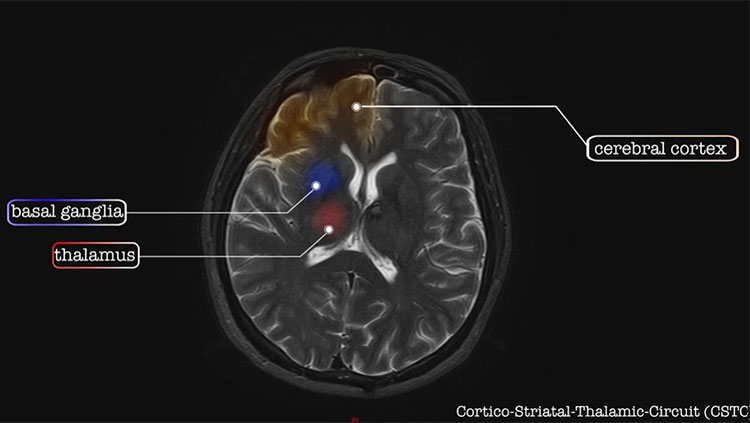

Bringing a treatment or vaccine for the Zika virus to the general population will require that scientists learn about how Zika affects primates similar to humans. Researchers at the National Primate Research Centers at the University of Wisconsin, University of Oregon, and the University of California, Davis are studying Zika in rhesus macaque monkeys to learn how the virus can impair fetal brain development in primates. Although slower and more difficult to work with, scientists can learn more from nonhuman primates like macaques than from rodents because their brains are similar to humans’. For instance, only macaques share the brain areas that appear to be most compromised by fetal Zika infection in humans. These scientists also hope to learn if Zika infection triggers immune responses that can protect against a future re-infection.

Using animal models of Zika virus infection, including rodents and nonhuman primates, is the quickest and most effective path to combatting this new threat to public health and developing treatments and preventative measures.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Childhood Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org