The Dementia Spurring People to Paint

- Published21 Feb 2024

- Author Nick Keppler

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

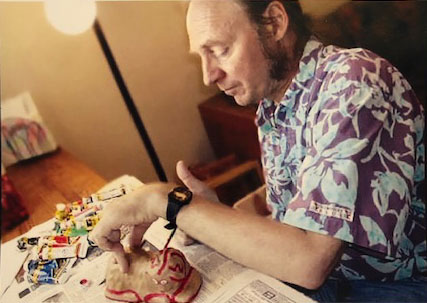

During his first interview at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Memory and Aging Center, Victor Wightman, then 53, wore a loud Hawaiian shirt, kept his greying hair in a ponytail, and took a gulp of water from a thermos exactly every 15 minutes. His tone was flat, and he paused before answering questions, which a researcher interpreted as a sign he couldn’t make spontaneous conversation.

It was 2002. A year prior, Wightman had been a struggling lawyer, working out of his Los Angeles home. He handled whatever cases came his way: divorce, immigration, personal injury, labor law. According to his sister, Rebecca Wightman, he earned his law degree in his mid-40s, after years spent driving buses and taxis.

Wightman suddenly quit practicing law and resumed taking odd jobs. His behavior became increasingly bizarre. He carefully timed his food and water intake, ceased bathing, and compulsively collected coins, sometimes taking them from tip jars.

He was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a type of dementia hallmarked by damage to the frontal and temporal lobes, parts of the brain associated with speech, memory, and executive function. It often manifests earlier than other dementias, in middle age, and may lead to disorders in behavior, language, or movement. Loss of inhibition and extreme personality shifts are common in the behavioral form of FTD.

As key brain functions diminished — vocabulary, self-awareness, capacity for planning and reasoning — he became a prolific and determined visual artist. He compulsively painted stick figure scenes and brightly-hued designs on furniture, household items, and proper canvases. Before this time, he only dabbled in sketching.

Many neurological conditions can affect creativity, said Alby Richard, a professor of neuroscience at the Université de Montréal. “In the neurology realm, there have been documented changes in creativity with almost every disease,” Richard said, “schizophrenia, stroke, epilepsy, personality disorders, learning deficits, autism.” These phenomena have been under-studied, he said, the subject of mostly individual case studies.

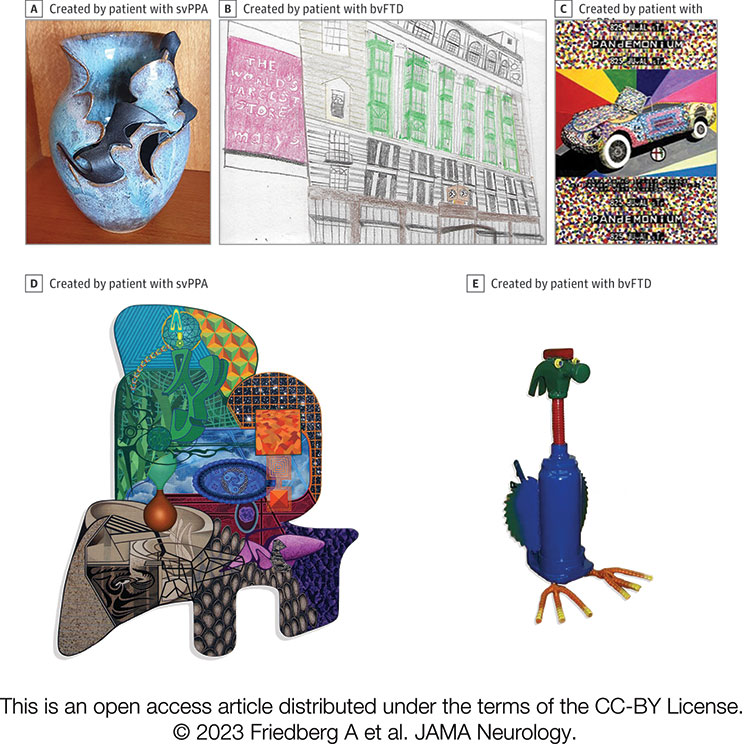

But the art of FTD has a unique flavor. In paintings, sculptures, ceramics, and montages collected by the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, bright colors are common, and works reveal a fixation on honing and capturing exact hues. Human faces are rare and, if present, have bizarre, pained expressions. Animals are often amorphous, rarely resembling an identifiable species.

The Unique Art of Frontotemporal Dementia

According to a 2023 estimate from the Alzheimer's Association, between 50,000 and 60,000 people in the U.S. live with FTD. Only a few experience this artistic drive.

This small but significant number of people with frontotemporal dementia develop a drive to create visual art. Some were not artists previously, but art becomes an intense focus, a final cerebral spark, as the disease robs them of other pursuits and interests. The reasons behind all this present a conundrum that researchers have tried to unravel for more than 25 years.

Neurologist Bruce Miller of UCSF first noted the connection between FTD and art in a 1996 letter to The Lancet. He described one of three artistically driven patients he had observed. Once a successful businessman, the man lost his social inhibitions in his mid-50s, followed by diminishment in his vocabulary and memory capacity. He took up art, first painting brightly colored shapes, “but later works were crafted with care,” Miller wrote. “He took hours to complete single lines.”

Wightman’s creative blast started with painting images of fish, whales, and amphibians all over the walls and floorboards of his house. When his sister asked why, he responded with a “little hee-hee.” The further the disease progressed, the more his art conformed to the features of FTD. He moved on to cartoony faces with strange grins and then intricate patterns with psychedelic color schemes.

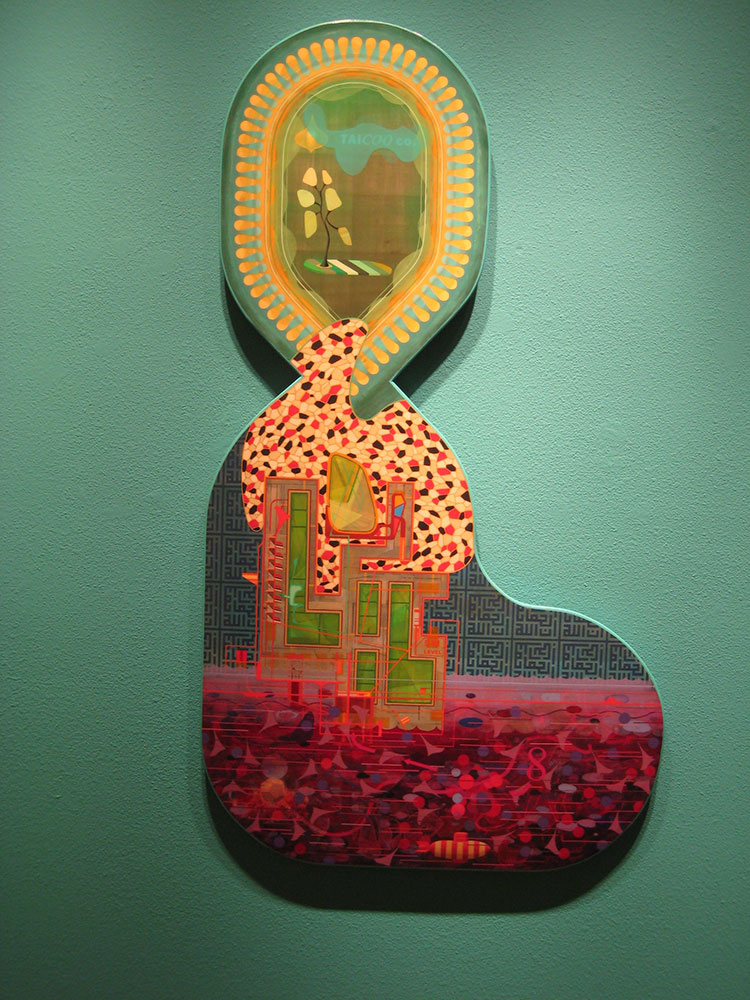

David Wetzl was an established artist and teacher when he was diagnosed at 54. His art had been postmodern, according to his widow, Diana Daniels, who as an art historian who teaches at California State University, Sacramento, is qualified to classify it. He worked in lines, shapes, symbols, and shades. Colors were sparse. He did entire paintings in smoky or metallic greys.

After his diagnosis, multiple patterns of shapes still played out within his paintings, but he started using a wide array of bright colors. Some of his later paintings were downright kaleidoscopic and true to the norms of art spurred by FTD. Otherworldly faces of African masks, seemingly with pained expressions, are hidden in some.

In Search of an Explanation

Wightman, who died in 2004, spent his final years in San Francisco where his family lived. He also suffered from ALS, which often coincides with FTD. When his muscles deteriorated so he could no longer lift his arms, he held a paintbrush at waist level and stood over the canvas. In his final days, he clenched it with his teeth.

Wetzl lost words for common objects, could no longer follow sports, and got into ugly confrontations with strangers (once “barking” at a family at a swimming pool). But he still went into his garage studio every day to paint until shortly before his death in 2020. “Whatever was going on in his brain, he was compelled,” his wife, Daniels, recalled. “It was like a motor.”

The UCSF Memory and Aging Center has generated several papers about the FTD and art phenomenon. In a February 2023 paper published in JAMA Neurology, researchers examined an ongoing study of 689 FTD patients. About 2.5% displayed visual art creativity. “Usually, it emerges around the time the language disorder or the behavioral disorder starts to manifest, or even before,” said lead author Adit Friedberg, “At this point, patients usually retain their ability to function.”

The team examined the lives and brain physiology of 15 patients who started or restarted creating art as FTD progressed, plus two established artists whose style took a turn. “They engage in this [artistic] activity for a long time,” said Friedberg, “for many hours a day.” Researchers examined structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data, comparing brain scans from people with a similar diagnosis (but no visual artistic drive) or a similar demographic to the artistic group.

The team noted that, as the frontotemporal lobe shrunk in patients, a “network rebalancing” seemed to increase activity in the occipital lobe, a part of the brain that processes visual imagery. However, this finding was not specific to the visually creative group: Around 90% of people with FTD and no visual artistic drive showed a similar rebalancing.

Scientists did find the artistic group had a greater motor cortex area volume increase in the region controlling right-hand movements as the occipital lobe volume increased. This plasticity may enhance the structural correlation between visual and motor areas of the brain, reflecting patients’ new preoccupation with visual art. Scientists aren’t sure whether this artistic preoccupation stems from an innate inclination to create art or a result of connections strengthening as people create art.

Art “does not require linguistic eloquence, memory, conceptual knowledge, or abstract reasoning,” wrote the authors of a 2018 JAMA paper, also from UCSF, and provides “a hidden window into the rich and varied experiential inner world of patients who may otherwise struggle to communicate in more conventional ways.” Friedberg said research hasn’t determined if art is therapeutic for FTD patients, but it is a good future topic. For Victor Wightman and David Wetzl, it anchored their lives, as all else fell apart.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Erkkinen, M. G., Zúñiga, R. G., Pardo, C. C., Miller, B. L., & Miller, Z. A. (2018). Artistic Renaissance in Frontotemporal Dementia. JAMA, 319(13), 1304–1306. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.19501

Friedberg, A., Pasquini, L., Diggs, R., Glaubitz, E. A., Lopez, L., Illán-Gala, I., Iaccarino, L., La Joie, R., Mundada, N., Knudtson, M., Neylan, K., Brown, J., Allen, I. E., Rankin, K. P., Bonham, L. W., Yokoyama, J. S., Ramos, E. M., Geschwind, D. H., Spina, S., Grinberg, L. T., … Miller, B. L. (2023). Prevalence, Timing, and Network Localization of Emergent Visual Creativity in Frontotemporal Dementia. JAMA Neurology, 80(4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.0001

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD). (2023). Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-dementia-frontotemporal-dementia-ts.pdf

Jones, S. (2023). Some dementia patients begin to create art. We may now know why. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/08/10/frontotemporal-dementia-visual-creativity/

Leigh, S. (2023). How a rare dementia transforms patients into artists. University of California. https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/how-rare-dementia-transforms-patients-artists

Liu, A., Werner, K., Roy, S., Trojanowski, J. Q., Morgan-Kane, U., Miller, B. L., & Rankin, K. P. (2009). A case study of an emerging visual artist with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurocase, 15(3), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554790802633213

Martone, R. (2023). A Rare Form of Dementia Can Unleash Creativity. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-rare-form-of-dementia-can-unleash-creativity/

Miller, B. L., Ponton, M., Benson, D. F., Cummings, J. L., & Mena, I. (1996). Enhanced artistic creativity with temporal lobe degeneration. Lancet, 348(9043), 1744–1745. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)65881-3

What Are Frontotemporal Disorders? Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment. (2021). NIH National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/frontotemporal-disorders/what-are-frontotemporal-disorders-causes-symptoms-and-treatment

What Is FTD and How Is It Connected to ALS? (2021). The ALS Association. https://www.als.org/blog/what-ftd-and-how-it-connected-als

What to Read Next

Also In The Arts & The Brain

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org