The Teen Brain in a Grown-up World

- Published19 Apr 2019

- Reviewed19 Apr 2019

- Author Kayt Sukel

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Ask any parent of a teenager about what life is like living with an adolescent and they’ll likely regale you with stories of unpredictable mood swings, risky behaviors, and poor decisions. Despite all the stress and drama involved with adolescence, it’s clear that it is also a time ripe for learning.

“At every developmental stage, whether we are talking about infancy or adolescence, there are challenges and demands we have to successfully meet to adaptively proceed to the next one,” said B.J. Casey, director of the Fundamentals of the Adolescent Brain Laboratory (FABLAB) at Yale University. “So many of these things we see as bad in adolescence aren’t bad, per se — they offer adolescents the ability to learn what they need to in order to grow into healthy, pro-social adults.”

Although we see the chaos of the teenage years, in fact, it is part of what helps adolescents grow into adulthood. So, how can society best support teens through this time, and help them as they make decisions?

A Brain “Imbalance”

Over the past decade, researchers like Casey have tried to understand how the brain changes and matures during adolescence. They’ve discovered that while cognitive abilities mature, on average, at about 16 or 17 years of age, a teenager’s performance on the tasks that measure those abilities is highly dependent on emotional and social information.

At Temple University, psychologist Larry Steinberg and neuroscientist Jason Chein, recruited teens for a simulated driving task while peers were watching them. The researchers were looking at what the teenagers did when they approached yellow lights — would they hit the gas and try to beat the red light, or would they hit the brakes and wait until the light changed back to green? Perhaps unsurprisingly, adolescents were much more likely to try to beat those yellow lights when their peers were looking on. But what may surprise you is why.

“When adolescents did the test with the knowledge that their friends were able to see them, it activated the brain’s reward centers and they tended to go through those yellow lights much more often. We didn’t see the same behaviors or such activation in adults,” Steinberg said, arguing that the results suggest that the teenage brain finds peer approval extremely rewarding. What’s more, when Steinberg and his colleagues investigated further, they saw a strong correlation between the brain’s reward centers and riskier behaviors.

“The more active those reward centers were, the riskier the participant behaved on the test, running more yellow lights,” he said. This suggests that the rewarding presence of friends may lead teens to engage in more risky behaviors than they otherwise would. And sure enough, when teens do the same task without their friends nearby, they performed much more like responsible, risk-assessing adults.

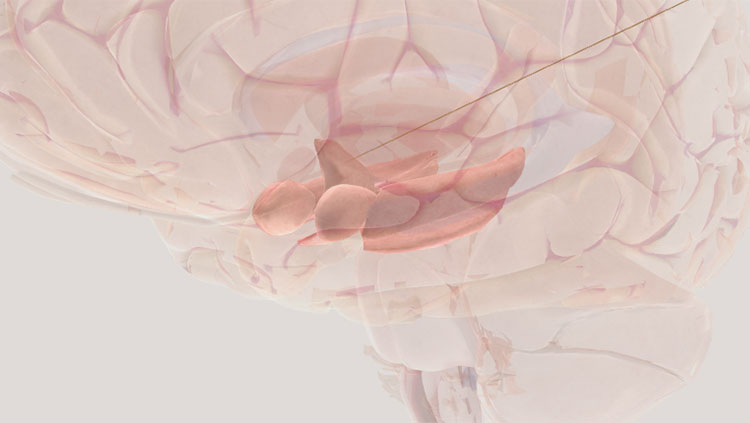

Other studies suggest brain regions involved with rewards and motivation, like the nucleus accumbens and striatum, mature much more quickly than the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s executive control center. The result is a neurobiological recipe for risk-taking: A brain that puts high premium on rewards but lacks the maturity to think things through and put the brakes on behaviors that could result in unhealthy consequences. Putting these different research pieces together, Casey hypothesizes that the adolescent brain is in a state of “imbalance,” with the reward regions of the brain having much more sway over decision-making and behavior than the executive control ones.

“We are seeing deep primitive emotional centers in the brain that change rapidly during adolescence. And they are changing before the prefrontal cortex is fully mature,” she said. “It’s the interactions of these regions, the circuits they make, that might be leading to some of the behaviors we see during the adolescent period.”

Yet, this “imbalance” isn’t all bad. Steinberg, who has authored a book on the teenage development called, Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence, says the newest brain research suggests that adolescence is a time of exceptional plasticity, where the brain can remodel itself in response to the environment. That heightened reward sensitivity may prime teens to take more risks, but also motivate them to get out into the world and learn the skills they need to become successful adults. It is likely why adolescence is a time of such great learning — with increased motivation and more of a social focus, teens have an opportunity to figure out the skills they need to successfully navigate the adult world.

“The truth is, adolescence isn’t inherently a bad or good time, but it’s a time when the brain is extremely sensitive from the contexts of their environment,” Steinberg said. “That should force us, as parents, educators, scientists, and policy makers, to make sure that the context in which kids are growing up are positive ones.”

Addressing Public Policy

Some researchers have suggested, due to this brain “imbalance,” teens should be more restricted in what kind of decisions they are permitted to make — and that the juvenile justice system should be revamped to respect the nature of the adolescent brain when it comes to sentencing recommendations. And, over the past decade, several high-profile court cases, like Roper v. Simmons, a case that deemed the death penalty unconstitutional for criminal offenders under the age of 18, have considered the latest neuroscientific findings concerning the lag in frontal lobe development in their legal decisions. And some have suggested, thanks to the newest research into teenage brain development, that the age of criminal jurisdiction should be raised past the 18-year mark as well.

But Gregory M. Lipper, a criminal and constitutional lawyer at Clinton & Peed in Washington, DC, says such a change may have unintended consequences.

“Eighteen is not some magic number — it’s not like you turn 18 and your brain is now fully developed,” he said. “It is a legally significant age when it comes to criminal law. But we also let people vote when they are 18. We send people off to war. We let people be police officers at 18 in some places. If we redraw this line, even if it is a semi-arbitrary line, we may see political bodies using that logic to add more restrictions on 18-year-olds. In a worst-case scenario, information about the teenage brain could be used to limit the rights of teenagers even more than they are limited now.”

That said, Lipper says he believes that the neuroscience of adolescent brain development has a role to play in informing criminal and civil law. And he hopes that neuroscientists can help better educate prosecutors, judges, and policy makers about the nuances of adolescent brain development so that teenagers are supported — and not treated like hardened criminals — when they make mistakes but are also not kept from the critical life experiences they need to become healthy adults. Casey agrees — and it’s why her lab is focused on investigating the situations where teenagers can make good decisions as well as the ones where they don’t.

“It’s important that our data isn’t misused. We see that teenagers have strong cognitive skills, where they’re up to adult [cognition] levels around 16 years of age. And they can make good decisions. In fact, they can often make good decisions much more quickly than you or I could when it’s not an emotionally charged moment,” said Casey.

By understanding the nuances of where, when, and how decision-making might be altered, for good or ill, during the teenage years, she has faith that society can come up with policies that reduce some of the damage of poor teenage decision-making — but interfere not with their overall development.

“Despite their reputations, teenagers make good decisions all the time. It’s important we don’t take away teens’ rights to make those decisions because we would be taking away their ability to learn and grow,” she said. “There’s a big difference between development and deviant — and it’s important that we, as scientists, help the public understand that. As parents, as policymakers, and as citizens, we can come together to make changes that protect the rights of young people and yet ensure their healthy brain development.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Breiner, K., Li, A., Cohen, A. O., Steinberg, L., Bonnie, R. J., Scott, E. S., … Galván, A. (2018). Combined effects of peer presence, social cues, and rewards on cognitive control in adolescents. Developmental Psychobiology, 60(3), 292–302. doi: 10.1002/dev.21599

Casey, B., Jones, R. M., & Somerville, L. H. (2011). Braking and Accelerating of the Adolescent Brain. Journal of research on adolescence: the official journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 21–33. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00712.x

Smith, A. R., Rosenbaum, G. M., Botdorf, M. A., Steinberg, L., & Chein, J. M. (2018). Peers influence adolescent reward processing, but not response inhibition. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 18(2), 284–295. doi: 10.3758/s13415-018-0569-5

Also In Childhood & Adolescence

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org