I've been reflecting on issues of Personal Identity; last month I wrote a blog post on this. On Saturday evening I rented Memento (2000) and watched for the second and third times.

This remarkable film features adventure, mystery, human drama and fascinating movie technique. Overriding all of these is the portrayal of memory and the mind. Although I've been studying memory for 30 years, Memento gave fresh perspectives. If the role of art is to present fresh insights by sharing the thoughts of others, Memento is true and impressive art.

Synopsis. On the surface, Memento is a standard detective story. Leonard, the central character, is focused on finding the man who, during a home invasion, murdered Leonard's wife and crushed Leonard's skull, leaving him with brain damage. The brain damage left Leonard with severe anterograde amnesia.* He remembers nothing between a time shortly after the attack and the present. He can operate in "the present", but, once events leave the present (when they exit "working memory"), all trace of these activities is lost.

The construction of the movie is brilliant. The director, Christopher Nolan, presents the scenes in reverse time-series. If one thinks of the events of the movie as a series in time, the last is presented first and the first, last. This leaves you, the viewer, extremely confused. When you view a scene, you don't know what led up to it. The brilliance is that you are viewing the scene as Leonard views it, since his brain has no store of the preceding events. You, the viewer, feel the confusion, frustration and lack of certainty that Leonard must feel every moment. This cinematic trick is riveting, and helps you understand and empathize with Leonard. You are no longer a detached, all-knowing observer. You are Leonard.

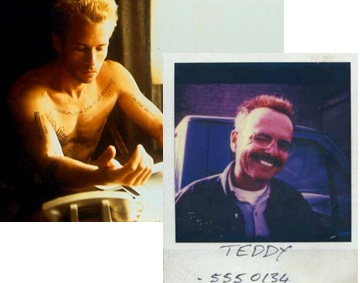

Initially we are impressed with Leonard. He has developed two clever strategies that help him deal with the disability: He tattoos himself with 'facts'; and he annotates polaroid pictures. These memory aids — mementos — are recorded before the "facts" can leave working memory. One-hundred percent of his energy is focused on finding his enemy. We are hopeful and convinced that Leonard, with his intelligence and drive, can overcome odds, achieve his goals, and live a fruitful life. But this is not to be.

Memento and the Mind. The key diner scene:

Leonard: Memory's unreliable.

Leonard: Look, memory can change the shape of a room, the color of a car; and memories can be distorted. They're just an interpretation; they're not a record. They're irrelevant if you have the facts.

Teddy: You really want to get this guy, don't you.

Leonard: Yeah. He killed my wife, he took away my f..n memory. (pause)

Leonard: He destroyed my ability to live.

Teddy: (feels Leonard's neck for pulse) You're livin'

Leonard: Only for revenge.

There are several psychological features at the core of the film. One is the accuracy of memory: does memory reflect reality or is it a story? Neuroscientists largely agree that both perception and memory, rather than being passive responses to events in the world are constructions. What we perceive and remember is a mix of raw sensory data and belief about what the world is or should be. The term confabulation is used when a perception or memory is based more on belief than reality. Confabulation is a common feature of dementia**. In Memento we are faced with the question of how much of Leonard's memory of the past is real and how much constructed from beliefs and wishes.

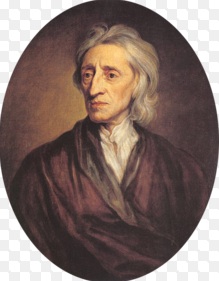

A second, and more important issue is the role of memory in personhood, in individual identity. My initial insight of the role of memory in personal identity came from reading John Locke, the 17th century English philosopher. For Locke, personal identity depends on the construction of a conscious story-line of self, a "same continued consciousness". According to Locke, self depends on mind, not substance:

Self depends on consciousness, not on substance ... personal identity consists: not in the identity of substance, but, as I have said, in the identity of consciousness

and the relation to memory,

Suppose I wholly lose the memory of some parts of my life, beyond a possibility of retrieving them, so that perhaps I shall never be conscious of them again ... Absolute oblivion separates what is thus forgotten from the person ...

Suppose I wholly lose the memory of some parts of my life ... But if it be possible for the same man to have distinct incommunicable consciousness at different times, it is past doubt the same man would at different times make different persons

Basil Smith summarizes this well: "Locke argued that personal identity is a matter of our conscious memories over time. Locke's conception of identity was, for me, a revelation. But the full impact did not hit until I saw Memento. By forcing the viewer to imagine life without memory, I could feel the sense of self oozing away. Without memory, self would be a mystery. Locke proposed a concept of personal identity based on memory; Memento takes the us into the mind of an amnestic mind and reveals the loss.

In sum, Memento takes us on a fantastic journey. Through remarkable cinematography and creative story-telling, Christopher Nolan guides us through the mind of Leonard and ourselves.

----------------------------------

* The brain region damaged was, almost certainly, the hippocampus. This is indirectly alluded to in the movie. Could have been due directly to a blow to the head, or, more likely, lack of oxygen to the brain. Bilateral damage to the hippocampus causes anterograde amnesia identical to the deficit described by Leonard.

A strange feature of the movie is that Leonard repeatedly mis-states his condition. He says he doesn't have amnesia; he says that he has a deficit in short-term memory. He has amnesia, and its not a deficit in "short-term memory". Here is a mixed bag of scientific fact and error. Leonard says that an amnestic can respond to conditioning. The example presented is that an amnestic can learn to avoid touching an object when the touch leads to shock. This is true. But he incorrectly calls this conditioned response an "instinct". An instinct is unlearned. This would be a conditioned (learned) response, not an instinct.

** I visited my grandfather in his apartment in New York weeks before he died. He said, "John, its so nice of you to go so far out of your way to visit." He thought we were in a beautiful hotel in Japan, not his bedroom. When my grandmother and I pointed out that each piece of furniture was part of his bedroom, he said that this was such a splendid hotel that they replicated his bedroom. I imagine his brain was giving mixed signals: each piece of furniture was familiar, but, due to his dementia, the combination was not familiar. He confabulated a lovely story that made sense of the conflicting messages.

Note added: Mo Costandi sent a link to an excellent article he wrote on Memory and Amnesia in the Movies. Goes into detail about Memento and current neuroscientific views of memory.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

John locke Essay concerning Human Understanding, book 2, chapter 27 http://hzt4umovies.wikispaces.com/file/view/2-Memento+and+Locke+Identity.pdf

Basil Smith "John Locke, Personal Identity and Memento". In The Philosophy of Neo-noir (2007) Mark Connard, ed. (I came across this essay by Smith after writing most of this blog post. The views are remarkably similar. The essay goes into greater detail on the relation between Nolan and Locke's view of personal identity.

Also In Learning & Memory

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org