The Fascinating Neuroscience of Lucid Dreaming

- Published23 Jul 2025

- Author Dina Radtke

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

In our dreams, we typically don’t question bizarre phenomena, like losing all our teeth or being chased by giant orange snakes. We accept the strange reality of our dream worlds, unable to find a reasonable explanation or solution.

That’s because during sleep, we lose the ability to reflect critically on our own thoughts and analyses, a process known as metacognition. But sometimes, something tips us off. It suddenly becomes clear — we don’t normally go to school in a giant dripping cave or have the ability to fly, and we realize: This is a dream.

The state of recognizing you are dreaming is known as lucid dreaming. In neuroscience terms, this happens when your capacity for metacognition comes back online. You’re able to examine your beliefs in the moment and assess whether the conclusions you’re drawing — like “my school is a cave” or “I was always able to fly” — jibe with reality.

“The mind is quite restricted during sleep and dreaming, but lucid dreaming is the exception. Our reflective capability can be as strong and intact as it is during wakefulness,” said Martin Dresler, principal investigator at the Donders Sleep & Memory lab at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

For the most part, we can't consciously choose what we dream about. But actively recognizing you are dreaming creates the opportunity for varying levels of dream control. Advanced lucid dreamers can alter the plot of their dreams, transform themselves into animals or other people, change their environment, and distort the laws of physics.

Most people lucid dream just a few times in their lifetime, if at all. And even if they gain an awareness of their dream state, it’s even more rare to be able to actively control their dream content in real time.

“Something like one in 1,000 or so people just spontaneously have lucid dreams on a regular basis,” said Benjamin Baird, an assistant research professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “It’s interesting that this segment exists.”

Piecing Together What Makes a Lucid Dream

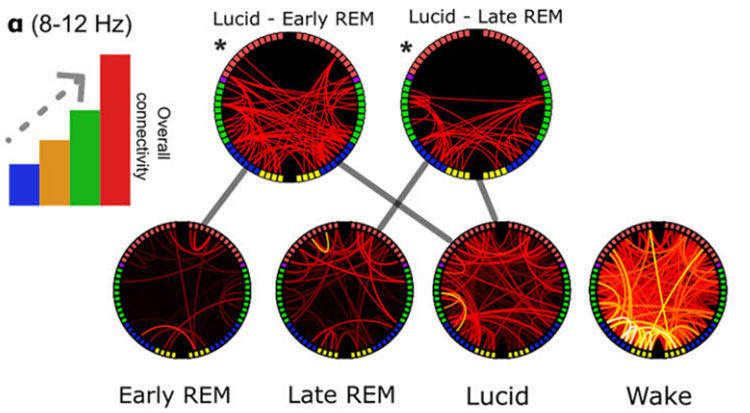

An April 2025 Journal of Neuroscience study led by Çağatay Demirel, a PhD researcher in Dresler’s lab, used EEG data from different labs around the world to try to get a clearer picture of the lucid dreaming brain. They found widespread communication across different brain regions. But when it comes to pinpointing which specific areas were particularly active, the picture is still quite fuzzy.

“After the initial Eureka-like insight of ‘I’m in a dream!’, this realization just lingers in the back of the lucid dreamer’s mind, whereas the ongoing dream scenario … [is] in the mental focus,” Dresler explained. Even though the brain regions involved in lucidity are active, their precise signals are obscured by the “neural noise” of the actual dream, he added, making their EEG recordings hard to capture.

fMRI studies do a better job of pinpointing activity in specific brain regions, but they are expensive, and because lucid dreams are so rare, there’s no guarantee a study participant will achieve the desired state while in the machine. In 2012, Dresler’s team successfully completed the only fMRI ever performed of an actively lucid dreaming brain. They found certain brain regions that are usually relatively quiet during REM sleep — including the prefrontal cortex, precuneus, and occipito-temporal cortices — showed activation in the person’s brain while lucid dreaming.

Six years later, Baird and his colleagues used fMRI to study the brains of 14 frequent lucid dreamers while they were awake and not performing any specific tasks. What they found was strikingly similar to Dresler’s observations of the brain while actively lucid dreaming: increased communication between the brain’s metacognition center — the prefrontal cortex — and parietal and temporal structures, which are associated with high-level cognition.

The findings indicate “a more tight-knit community of higher-order association hubs in the brain[s]” of frequent lucid dreamers, said Baird. This research suggests frequent lucid dreamers have a relatively high capacity for things like metacognition and cognitive control, or the ability to regulate thoughts, attention, and emotions.

The Effect of Dreams on Waking Life

Those with strong dream control use this power in a variety of ways, from spiritual development to overcoming deep-seated fears. Some lucid dreamers even use their sleeping hours to train for sports or dance performances or process problems they face in waking life.

But according to one study, the most common application of lucid dreaming is wish fulfillment. Lucid dreamers are able to carry out desires out of reach in waking life, like exploring outer space or interacting with a loved one who passed away. Even though these scenarios did not happen in real life, the pleasurable experiences of lucid dreams seem to have a “spill-over effect” into waking life, leading to positive daytime mood.

These insights have sparked a new interest in exploring lucid dreaming’s potential for treating mental health disorders. In 2018, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine started to recommend it as a therapy for nightmare disorders, including those associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Neuroscientists have also found ways to treat insomnia with lucid dream therapy, which can ameliorate some psychiatric symptoms.

But turning lucid dreaming into a treatment may not be so simple, and such a therapy would carry a unique set of risks. Failed attempts at lucid dreaming can result in sleep paralysis — waking up but being temporarily unable to move — or false awakening — the disorienting experience of thinking you’re awake and carrying out your day, only to realize you are still asleep. Such experiences can blur the line between dream life and reality, which can exacerbate symptoms for those prone to delusions or hallucinations.

A Rare Gift, But A Learnable Skill

Still, the allure of reaching this rare state of consciousness has led to creative ways to try to get there. Techniques to induce lucid dreaming are difficult to master and almost guarantee multiple nights of interrupted sleep. In the 1990s, lucid dream induction headsets hit the commercial market, but their high price tags and varying effectiveness make them a controversial choice.

Baird and his team found the Alzheimer’s drug galantamine, which is used to treat memory and other cognitive impairments, increases lucid dream frequency by up to 42% compared to placebo. The drug increases levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter known to play a role in REM sleep, which is when most lucid dreaming occurs.

However, some believe the therapeutic potential of lucid dreaming comes by building the skills of metacognition and cognitive control. Researchers are studying how practices reinforcing these skills like meditation may encourage lucid dreaming while offering the added benefits of stress reduction, improved sleep, and other enhanced markers of well-being.

Baird described meditation as neurocognitive training for the very skills required to lucid dream. “You kind of develop this ‘witness mode’ where you’re recognizing the state of your mind,” said Baird. “You also have to be able to notice if your mind has drifted from the target and then bring it back, and so that involves a kind of metacognitive reflection.”

Research shows long-term meditators are prone to lucid dreaming. But in a 2019 study, when Baird and his team had non-meditators undergo eight weeks of mindfulness training, they found no increase in lucid dream frequency.

He believes the meditation protocol was simply too weak. “It was kind of like an intro to meditation,” he said. “It’s not like, say, going on a two-month retreat where you’re meditating for eight hours per day.” And one of Baird’s recent studies suggests some meditation styles may be more effective in facilitating lucid dreaming than others.

An Ancient Practice to Control Your Dreams

“Mindfulness is the tip of the iceberg,” said S. Gabriela Torres-Platas, a neuroscientist at Northwestern University. She is studying the effects of Tibetan dream yoga on sleep and mental health. This contemplative practice incorporates a variety of meditative exercises into waking and sleeping life, and its specific goal is to induce lucid dreams for personal insight and spiritual growth.

Before bed, a practitioner might review the events of their day, assessing whether their actions demonstrated a mindful, volitionally controlled response or a reactive, emotionally dysregulated response.

Those moments of reacting without thinking “create non-lucidity,” said Katie Love, a dream yoga practitioner and participant in Torres-Platas’ study, suggesting that a lack of awareness over our actions in waking life encourages a lack of awareness in dream states.

Dream yogis perform seemingly impossible tasks in their lucid dreams, like transforming into different dream characters, walking through walls, or multiplying one object into thousands of copies. These techniques allow practitioners to help cultivate mastery within their dream worlds, which may foster a greater sense of empowerment and agency in their waking lives.

“We perceive the world as rigid and solid,” said Torres-Platas, but “when you can go into a dream and change your environment by, for example, walking through a wall, you train your mind for flexibility” in the real world.

She hypothesizes that practicing specific meditation techniques while awake, combined with lucid dreaming while asleep, may help ease symptoms of anxiety and depression by increasing one's insight and control over their thoughts and emotions.

“You have learned to react in a certain way, so it bypasses conscious awareness,” said Torres-Platas, highlighting how automatic patterns can override metacognition and self-regulation. “It’s like when someone insults you, and you snap back — there’s no space for reflection or choice in the moment.”

She said the deep self-reflection required to gain lucidity while dreaming may teach us how to better navigate difficult circumstances. Instead of persisting in a mindset of agony or hopelessness, we can reflect on how we process and analyze the world, which gives us the opportunity to reframe our thoughts. Where pessimistic beliefs leave us stuck in a swirling pit of despair, lucid dreaming might open a path to something else.

Editor’s note: The name of the lead author of the April 2025 Journal of Neuroscience study, “Electrophysiological Correlates of Lucid Dreaming: Sensor and Source Level Signatures” has been added.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Baird, B., Castelnovo, A., Gosseries, O., & Tononi, G. (2018) Frequent lucid dreaming associated with increased functional connectivity between frontopolar cortex and temporoparietal association areas. Scientific Reports, 8. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-36190-w

Baird, B., Riedner, B., Boly, M., Davidson, R., & Tononi, G. (2019) Increased lucid dream frequency in long-term meditators but not following MBSR training. Psychol Conscious (Wash D C), 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000176

Bonamino, C., Watling, C., Polman, R. (2024) Sleep and lucid dreaming in adolescent athletes and non-athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 42(16). https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2024.2401687

Carr, Michelle. (2024). “The New Science of Controlling Lucid Dreams.” Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/engineering-lucid-dreams-could-improve-sleep-and-defuse-nightmares/ Accessed 20 June 2025.

Demirel, C., Gott J., Appel, K., Luth, K., Fischer, C., Raffaelli, C., Westner, B., Wang, X., Zavecz, Z., Steiger, A., Erlacher, D., LaBerge, S., Mota-Rolim, S., Ribeiro, S., Zeising, M., Adelhofer, N., & Dresler, M. (2025). Electrophysiological Correlates of Lucid Dreaming: Sensor and Source Level Signatures. Journal of Neuroscience, 45(20). https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2237-24.2025

Dresler, M., Wehrle, R., Spoormaker, V., Koch, S., Holsboer, F., Steiger, A., Obrig, H., Samann, P. G., & Czisch, M. (2012) Neural Correlates of Dream Lucidity Obtained from Contrasting Lucid versus Non-Lucid REM Sleep: A Combined EEG/fMRI Case Study. Sleep, 35(7). https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1974

Gerhardt, E. & Baird, B. (2024) Frequent Lucid Dreaming Is Associated with Meditation Practice Styles, Meta-Awareness, and Trait Mindfulness. Brain Sci. 14(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14050496

LaBerge, S., LaMarca, K., & Baird, B. (2018). Pre-sleep treatment with galantamine stimulates lucid dreaming: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. PLoS One, 13(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201246

Schofield, Daisy. (2021). "Lucid dreamers are using unproven tech to hack their sleep." Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/lucid-dreaming-tech/#:~:text=The%20ZMax%20headband%20combines%20Remee,the%20market%2C%E2%80%9D%20says%20Pavlou. Accessed 10 February 2025.

Stumbrys, T. & Erlacher, D. (2016) Applications of lucid dreams and their effects on the mood upon awakening. International Journal of Dream Research, 9(2). https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/IJoDR/article/view/33114

Tzioridou, S., Campillo-Ferrer, T., Cañas-Martín, J., Schlüter, L., Torres-Platas, S. G., Gott, J., Soffer-Dudek, N., Stumbrys, T., Dresler, M. (2025) The clinical neuroscience of lucid dreaming. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106011

What to Read Next

Also In Sleep

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org