Turning on Flow Means Turning Off Parts of the Brain

- Published12 Mar 2024

- Author Nick Keppler

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Stephen Curry rose to the top of the NBA by thriving on risk. Since his rookie year, the Golden State Warriors point guard has been outmaneuvering defenders to score shots from behind the three-point line. He has scored on 90.9% of his attempts at free-throws, which is an all-time NBA record.

But at his best moments, Curry is not assessing his odds. Instead, he says, he “kind of goes autopilot.”

Curry has described the mental state that athletes call “in the zone,” where reactions come quick and feel intuitive, and the player feels at one with the game. “There’s this synergy with everything you’re trying to do,” he says. “Even your intentions have been validated by the atmosphere around you, where it seems like everything else is going right at the same time, and you kind of get lost in that moment.”

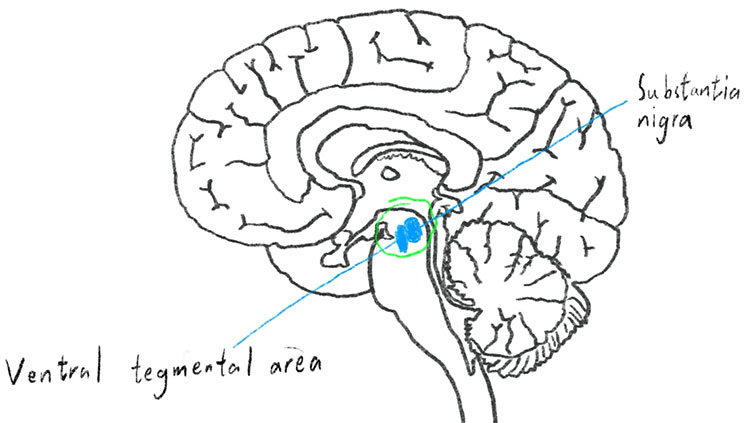

Curry’s brain may actually undergo a shift when he enters “the zone.” Brain scientists have observed reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex, a brain area associated with planning, judgment, and other high-level executive functions, during some intense activities. Researchers think that as activity decreases in this part of the brain, the mind temporarily alters its cognitive state and enters a state of “flow.”

For 20 years, this theory, called the transient hypofrontality hypothesis, has been applied to a range of experiences where one gets absorbed in a task: athletes at peak performance, artists during creative spurts, meditation practitioners maintaining calm for hours, and even some of the joys of sex.

The Theory in the Making

The theory goes back to one grad student trying to understand how he chugged through marathon jogs in the Georgia heat.

German-born psychologist Arne Dietrich, the architect of the transient hypofrontal hypothesis, competed in triathlons while working on his doctorate at the University of Georgia. In an interview with BrainFacts, Dietrich said, as training, he once completed a 21-mile run through the woods. He noticed he didn’t think of the arduousness of the workout or the heat. He just kept going.

“I realized the way my cognition and my emotion changed were really the kinds of things that you typically attribute to the frontal cortex, these higher cognitive functions that particularly make us ‘us’ and not some other ape: executive attention, working memory, these sort of things,” he said.

The idea of entering a “flow” state was not new. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, known as the “father of flow,” had pioneered its study. He once described it as “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz.” To Csikszentmihalyi, flow was a component of purpose and contentment, a heightened state.

A Theory Takes Shape — and Critique

Dietrich wondered if, during flow, some switches in the brain were being turned not on, but off.

In 2003, he published a paper outlining the transient hypofrontality hypothesis. He cited past studies of brain activity during dreams, daydreams, endurance running, meditation, hypnosis, and drug use, which all seemed to show diminished activity in the prefrontal cortex.

The first clinical study to cite Dietrich’s theory was published in 2008. Charles Limb and Allen Braun, then both at the National Institutes of Health, recruited six jazz pianists to perform as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) recorded their brain activity. They were told to improvise. It was one of the first studies to observe the brain during music generation. Limb and Braun found “extensive deactivation” of the prefrontal cortex and a boost in sensorimotor areas.

Later references to Dietrich’s theory expanded to research into an ever-growing range of pursuits and mindsets. Belgian scientists outfitted a professional tightrope walker with an electrode cap. Chinese researchers put subjects in an MRI scanner and asked them to practice calligraphy. A team in the U.S. took saliva samples, replete with data on cortisol levels, at an annual ritual in which members of a leather-clad subculture attach weights and hooks to their piercings and dance to the rhythm of drummers. They all observed signs of shifts in hypofrontality.

The theory has met some criticism from researchers who say it conflates creativity with flow. “Flow has often been simplistically assimilated to creativity and it has been assumed that also creative performance depends on low prefrontal activity,” wrote neurobiologist Alberto Oliverio. Those who are serious about creative pursuits, he argues, learning new skills, and revising works in progress, rely on skills like evaluation and problem-solving, carried out in the prefrontal cortex.

The Birth of New Theories

Many researchers studying hypofrontality are looking to better map an elusive mental experience, but some see practical applications in harnessing the power of flow.

Orli Dahan, head of consciousness studies program at Tel-Hai College in Israel, has built an entire theory of "birthing consciousness" on transient hypofrontality theory. The flow-like mindset that some women describe during childbirth makes for “an extremely positive experience of this focused attention, calm, reduced pain, and reduced anxiety sensations,” said Dahan. Characteristics include distorted perception of time, a sense of separation from one’s surroundings, and a shift to a less verbal state.

It is, she argues, an altered state of consciousness, with markers like those attributed to transient hypofrontality, like meditation. But the atmosphere of an average hospital or birthing center would pull someone out of the zone, she says. “Try to imagine meditating in a typical birth room,” Dahan says. “It’s not possible. There are many other distractions, such as loud voices and the smells and strangers coming into the room.”

There are few studies on women’s brains during birth; researchers tend to focus on before and after. But if one could show childbirth leads to this kind of altered state, and that it is a positive, natural adaptation, maternity wards could be retooled to help ease women into a state of flow.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Avirgan, J. (2023). The Truth About "The Zone" (with Steph Curry). Good Sport, a TED Audio Collective. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tSP1M052Sg

Dahan O. (2020). Birthing Consciousness as a Case of Adaptive Altered State of Consciousness Associated With Transient Hypofrontality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 794–808.https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620901546

Dietrich A. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: the transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Consciousness and Cognition, 12(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1053-8100(02)00046-6

Filho, E., Dobersek, U., & Husselman, T. A. (2021). The role of neural efficiency, transient hypofrontality and neural proficiency in optimal performance in self-paced sports: a meta-analytic review. Experimental Brain Research, 239(5), 1381–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-021-06078-9

Geirland, J. (1996). Go With The Flow. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/1996/09/czik/

Lee, E. M., Klement, K. R., Ambler, J. K., Loewald, T., Comber, E. M., Hanson, S. A., Pruitt, B., & Sagarin, B. J. (2016). Altered States of Consciousness during an Extreme Ritual. PloS One, 11(5), e0153126. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153126

Leroy, A., & Cheron, G. (2020). EEG dynamics and neural generators of psychological flow during one tightrope performance. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 12449. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69448-3

Limb, C. J., & Braun, A. R. (2008). Neural substrates of spontaneous musical performance: an FMRI study of jazz improvisation. PloS One, 3(2), e1679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001679

Manna, A., Raffone, A., Perrucci, M. G., Nardo, D., Ferretti, A., Tartaro, A., Londei, A., Del Gratta, C., Belardinelli, M. O., & Romani, G. L. (2010). Neural correlates of focused attention and cognitive monitoring in meditation. Brain Research Bulletin, 82(1-2), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.03.001

Oliverio, A. (2008). Brain and Creativity. Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement, 173, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.173.66

Stephen Curry has the best career free-throw percentage, at 90.9 percent. (2024, March 12). StatMuse. https://www.statmuse.com/nba/ask/player-with-highest-career-free-throw-percentage

van Heerden, A. (2020). The restructuring of temporality during art making. South African Journal of Art History, 31(2). https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC-696b1aaff

Wang, Y., Han, B., Li, M., Li, J., & Li, R. (2023). An efficiently working brain characterizes higher mental flow that elicits pleasure in Chinese calligraphic handwriting. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991), 33(12), 7395–7408. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhad047

Williams, D. J., & Sprott, R. A. (2022). Current biopsychosocial science on understanding kink. Current Opinion in Psychology, 48, 101473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101473

What to Read Next

Also In Thinking & Awareness

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org