What the Rat Brain Can Tell Us About the Connection Between PTSD and Opioids

- Published30 Jan 2018

- Reviewed30 Jan 2018

- Author Courtney Columbus

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

What can the flick of a rat’s tail tell us about opioid addiction? More than you might think.

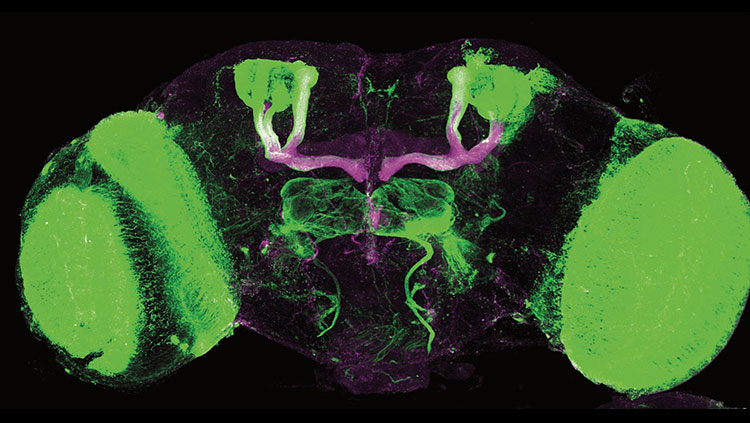

Elena Chartoff, assistant professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Harvard Medical School’s McLean Hospital, started studying opioids more than a decade ago. Now, she uses rodent models of opioid addiction to understand the links between distress intolerance — the perceived inability to tolerate negative physical and emotional states — and opioid abuse.

In a study Chartoff presented at Neuroscience 2017 in Washington, D.C., rats less able to cope with distress chose to take more doses of oxycodone, a prescription opioid painkiller. Chartoff says this could mean that distress-intolerant rats are more vulnerable to becoming dependent on opioids — and the same could also be true in people. If so, distress intolerance measures could be used to help evaluate a person’s risk of becoming dependent on opioids — before they are ever prescribed the drug.

The opioid epidemic continues to claim about 90 lives across the U.S. each day, according to the CDC.

“If we can, in a regular [doctor’s] office visit, take these measures of distress intolerance and have that in your file,” doctors could more easily determine if you are at a higher risk of abusing opioids in the event you ever need prescription painkillers, Chartoff says.

In the study, Chartoff and her colleagues tested about two dozen rats’ responses to tests designed to measure their distress intolerance. One test measured how much time it took each rat to flick its tail out of a warm water bath. The second test measured how much a buzzing sound startled rats. Rats that flicked their tails out of the water faster and were more startled by the sound are more distress intolerant.

“The faster they pulled their tail out of the water initially — you can imagine them saying, oh, that’s too hot!” Chartoff says. “They ended up being the ones that took the most drugs, the most oxycodone.” This was particularly true for the female rats in her study, though she found similar trends in male rats too.

Kathryn McHugh, assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, says researchers don’t know yet whether opioid misuse is a cause or consequence of distress intolerance in people. Chartoff’s research may be able to offer clues.

McHugh hopes to see mental health-related topics like heightened response to stress or pain become a bigger part of the conversation around how to tackle the opioid epidemic.

“A lot of the focus, understandably, is on ‘Let’s get as many people in treatment as we can, and let’s focus on overdose prevention,’” she says. “The depression, anxiety, trauma contribution to this epidemic is really huge, and I think for us to really make a significant dent in this epidemic, it has to be addressed more head-on than it is right now.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Addiction

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org