Bullying and the Brain

- Published30 Apr 2015

- Reviewed30 Apr 2015

- Author Mary Bates

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Brain research is revealing that bullying is more than just an unfortunate part of growing up. It can cause long-term changes to the brain that leads to cognitive and emotional deficits as serious as the harm done by child abuse.

Being bullied is a stressful experience. Victims of bullying often struggle with anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, and drug abuse — during the bullying and well into adulthood.

It turns out that long-term changes to the brain may be behind these behavioral issues. Bullying can leave a lasting mark on the developing brain, and brain science is starting to show how devastating and persistent the scars of bullying can be.

Stressed Out

Bullying can alter levels of stress hormones, and research in animals and people shows how this can affect brain function.

Chronic stress in humans is a known risk factor for drug abuse, and scientists want to know if being a victim of bullying poses a similar risk. To study this, scientists like Klaus Miczek, a psychologist at Tufts University, model bullying in rodents, often by putting an older, more aggressive rat or mouse in the cage of a juvenile animal. The dominant animal pushes the younger one around, maybe even biting it to show it who’s boss.

Miczek has found that bullied animals have higher amounts of the stress hormone corticosterone in areas of the brain that process rewarding stimuli, like drugs of abuse. He also saw that too much of the hormone can remain in these brain areas long after the stress has ended, possibly leading to a propensity to abuse drugs. When given access to drugs like cocaine and alcohol, Miczek’s bullied rodents took more of the drugs than non-bullied animals, even months later when they were adults.

The most interesting aspect of this research, Miczek says, is how little social stress it takes to lead to a persistent, long-lasting effect. "In rats, it only requires four episodes of social stress, which are five minutes long each," he says. "And the effects of that are seen into adulthood."

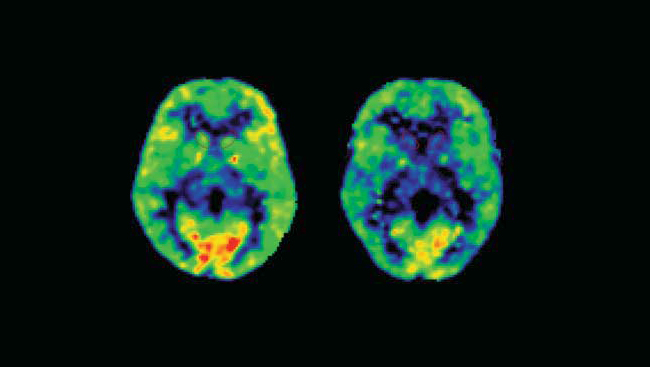

Bullying can also alter stress hormones in humans. In a long-term study of teenagers, Tracy Vaillancourt, a psychologist at the University of Ottawa, found that bullied boys and girls have abnormal levels of cortisol compared to their non-bullied peers. Abnormal cortisol levels can weaken the immune system and can even kill nerve cells in the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory. In fact, Vaillancourt has found that bullied teens perform more poorly on memory tests designed to examine hippocampal functioning compared to their non-bullied peers, suggesting that their abnormal cortisol levels might be affecting their brains.

Immune to Stress

Social stress also has a dramatic effect on immune system functioning, which in turn can negatively affect brain function.

When exposed to stress, our bodies produce more white blood cells, which in turn produce and release more pro-inflammatory substances that normally function to help the body fight off infection. In the case of chronic stress, scientists think the body produces too many white blood cells, resulting in sustained production and release of pro-inflammatory substances.

"When you experience chronic social stress, you have the immune response, but it doesn't turn off properly," says Scott Russo, a neuroscientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "The immune system ramps up and doesn't shut down, and that then causes damage such as nerve cell death. In vulnerable individuals, these changes can last for months following the stress."

However, Russo found that some animals are resilient in the face of social stress. When exposed to an aggressive adult, these individuals had fewer white blood cells and pro-inflammatory substances. Russo thinks there is some mechanism by which resilient individuals dampen negative inflammatory responses to stress.

To illustrate the connection between the immune system and behavioral resilience, Russo and his colleagues took immune system cells from resilient mice and injected them into stressed mice. They found that, following the injections, stressed mice showed less social avoidance and anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure. In effect, the stressed animals received the benefits of the resilient animal's immune system.

The results show that social stress can lead to a heightened immune response which, in turn, can lead to changes in behavior. Russo’s research suggests that dysregulation of the immune system, like that linked to chronic social stress, can lead to psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

A Vicious Circle

Not only do victims of bullying experience heightened stress and immune responses, but research in animals suggests that they might also be more likely to become bullies themselves.

Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin studied social stress in hamsters and found that juvenile hamsters who were bullied by an adult became more aggressive toward smaller animals, while being fearful and subordinate with hamsters of similar size or larger.

"Basically, a bully victim becomes a victimizer," says Yvon Delville, who led the study.

Delville also examined the hamsters' brains and found that socially-stressed hamsters showed changes in the levels of the neurotransmitters vasopressin and serotonin. In people, high levels of vasopressin are associated with increased aggression, while serotonin is known to inhibit aggression.

Bullied hamsters had lower levels of vasopressin and higher levels of serotonin than their non-bullied littermates. Delville is currently determining how these changes in neurotransmitter levels lead to enhanced aggression, and he suspects the aggression is secondary to changes in brain areas that govern more general features of behavior, such as impulse control.

Delville's results suggest adolescence may be a sensitive period for the development of aggressive behavior in adulthood, with chronic social stress making it more likely that victims will become bullies themselves. He says his results support what is often observed in humans: where you have violence against children, you'll find children becoming violent.

"People argue that bullying is a rite of passage or it builds character, but that idea is so misguided," Vaillancourt says. "Our work supports the idea that bullying is actually a seriously harmful event in a child's life. It's a public health issue, because it affects so many children adversely and the biological evidence supports that it confers a risk for future health problems."

Not all bullied kids have long-term damage to their brains or changes in their behavior, but those who do may carry these neurological scars for a lifetime. Brain research is helping to recast bullying as a serious form of childhood trauma with the potential to cause long-term chemical and structural damage to the brain.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Burke AR, Miczek KA. Stress in adolescence and drugs of abuse in rodent models: role of dopamine, CRF, and HPA axis. Pschopharmacology 231(8): 1557-1580 (2014).

Christoffel DJ, Golden SA, Russo SJ. Structural and synaptic plasticity in stress-related disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 22(5): 535-549 (2011).

Delville Y, Melloni RH Jr., Ferris CF. Behavioral and neurobiological consequences of social subjugation during puberty in golden hamsters. The Journal of Neuroscience. 18: 2667-2672 (1998).

Norman KJ, Seiden JA, Klickstein JA, Han X, Hwa LS, et al. Social stress and escalated drug self-administration in mice I. Alcohol and corticosterone. Psychopharmacology. 232(6): 991-1001 (2015).

Russo SJ, Murrough J, Han MH, Charney DS, Nestler EJ. Neurobiology of resilience. Nature Neuroscience. 15(11): 1475-1484 (2012).

Vaillancourt T, Duku E, Becker S, Schmidt L, Nicol J, et al. Peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and high salivary cortisol predict poor memory in children. Brain and Cognition. 77: 191-199 (2011).

Vaillancourt T, Duku E, deCatanzaro D, MacMillan H, Muir C, et al. Variation in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity among bullied and non-bullied children. Aggressive Behavior. 34: 294-305 (2008).

Vaillancourt T, Hymel S, McDougall P. The biological underpinnings of peer victimization: Understanding why and how the effects of bullying can last a lifetime. Theory into Practice. 52: 241-248 (2013).

Also In Childhood & Adolescence

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org