Dana Alliance member Gary Landreth, Ph.D., is a professor of neurosciences and neurology and the director of the Alzheimer Research Laboratory at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. In recognition of National Alzheimer’s Disease Awareness Month, he spoke to us about his career, clinical trials, and the pressures to find answers to the Alzheimer’s puzzle.

What interested you about Alzheimer’s research? I was recruited to my present job specifically because I had not previously worked on Alzheimer’s disease (AD). That was thought to be a virtue. My independent scientific career was focused on how growth factors elicit their effects in neurons. I moved to the newly established Alzheimer Research Laboratory at Case Western Reserve University in 1989 to investigate how growth factors might impact AD pathogenesis and whether they might represent a therapeutic approach to the disease. My research gravitated to the study of the innate immune responses in the brain. Specifically, we investigate how microglia respond to amyloid accumulation and promote its clearance. This remains the focus of work in the lab.

Why was it an advantage that you hadn’t worked on AD before? The idea was they wanted someone with a fresh perspective in a field that was then dominated by pathology-based investigations. It was at the dawn of the molecular age in AD. I was a biochemist focused on intracellular signaling mechanisms, which was then a rarity.

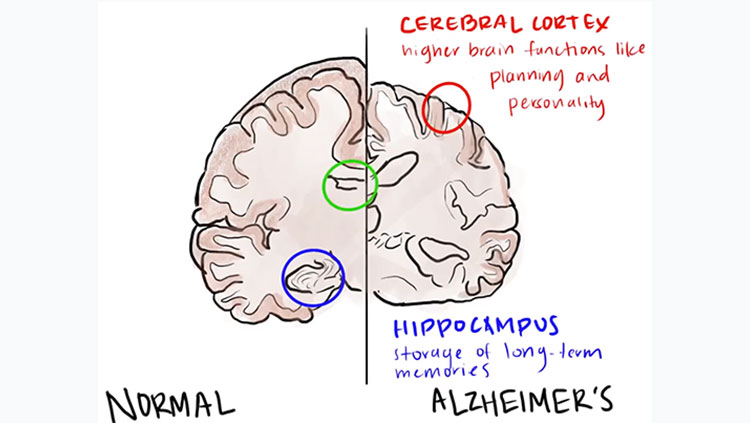

What are some of the biggest challenges facing Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers? The central issue confronting AD patients and their families is that there is no effective treatment for the disease. This fact cannot be minimized. The relentless and slowly progressive nature of the disease robs its victims of their memories and capacity to reason. The only solution is greater knowledge of the basic biology of the brain. This is an absolute prerequisite to developing new therapeutic approaches to the disease.

I know you’re working on a clinical trial. What can you tell me about this one in particular and the importance of clinical trials in general? My colleagues and I have initiated a Phase 1b proof of mechanism clinical trial of a repurposed drug, bexarotene. We expect to know the outcome of the trial in early 2015. Clinical trials are absolutely essential to establish therapeutic efficacy of any potential AD treatment. The field has been remarkably unsuccessful in developing and testing new drugs for AD. The design and execution of clinical trials are undergoing substantial reevaluation, owing to new thinking about which patient populations to engage and when to initiate treatment. A significant problem is that there are few promising drugs in development for AD to test in the clinic.

Have you found that AD patients turn to “unproven” or potentially unsafe drugs out of desperation? One of the most influential experiences in my career followed from our publication of work describing a drug that was efficacious in mouse models of AD. My office and laboratory phones rang continuously for several months. We received hundreds of e-mails and letters from individuals who wanted to know how they could obtain the drug or enter a clinical trial. Unfortunately, we have nothing to offer the patients and their families and it is entirely understandable that they are desperate. There is now much attention to diet and lifestyle changes and, thankfully, very few examples of individuals resorting to unsafe remedies.

Do you ever feel pressure to get answers to the AD puzzle as quickly as possible given that the population is living longer? I am no different from the many other scientists and clinicians in understanding the urgency in developing new treatments for AD. I also think we need to be quite clear that new therapies for AD will only arise from a more sophisticated understanding of basic biology of the brain. However, the problem has engaged some of the finest scientific talent and an array of new technologies. Progress is being made, albeit slowly. The resources devoted to this effort are modest in relation to its impact on the health care system and society in general.

–Andrew Kahn

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

The Dana Foundation is a private philanthropic organization that supports brain research through grants and educates the public about the successes and potential of brain research.

Also In Neurodegenerative Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

.jpg)