The Risks of Even Mild COVID-19: 1 in 4 Showing Cognitive Deficits After Mild Case, Brazilian Study Finds

- Published17 Jan 2023

- Author Christine Won

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Entering year four of the coronavirus pandemic, you probably have had or know someone who has had a mild case of COVID-19, gotten better, and carried on with life as before. However, new research suggests even a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection could lead to persistent and even long-term consequences, some that may not be known for years or even decades.

While the consequences of severe COVID-19 have been well documented and studied in recent years, mild COVID-19, which accounts for over 80% of cases worldwide, garners a paltry level of research in comparison. Recent research on the lingering effects of COVID-19 on the brain presented at Neuroscience 2022 in San Diego, the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting, focused on what investigators called “under-studied” groups: those with mild-COVID-19 and children.

In one study, researchers in Brazil found people who had mild COVID-19 symptoms showed “persistent cognitive impairment” months post-infection, where some were complaining of bumping into things or not being able to park the car due to altered depth perception and visual processing. “Everybody was worried about severe COVID, but the number of people with mild COVID is four times higher,” says Marco Romano-Silva, of the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil and senior author of the study published in June in Molecular Psychiatry.

“We found mild COVID was associated with the development of important persistent cognitive deficits even in younger adults.”

After casting an open invite for people between the ages of 18 and 60 who previously had a mild case of COVID-19, Romano-Silva and colleagues in the preliminary study tested a group of 130 volunteers comprised mostly of women with a mean age of 38 years about four to six months post-infection with mild COVID-19. “We found mild COVID was associated with the development of important persistent cognitive deficits even in younger adults,” Romano-Silva says.

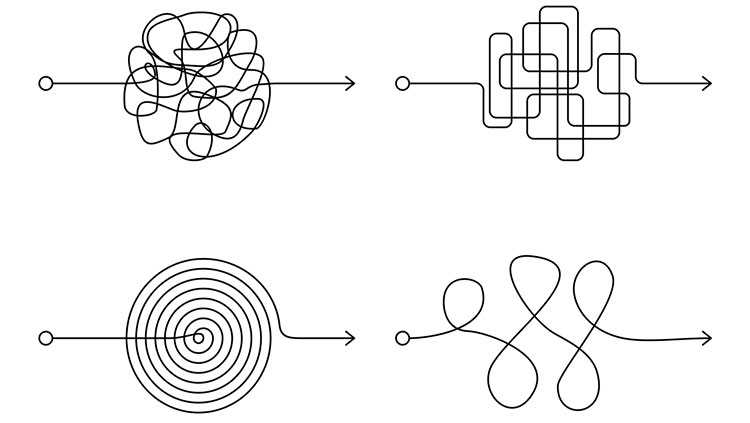

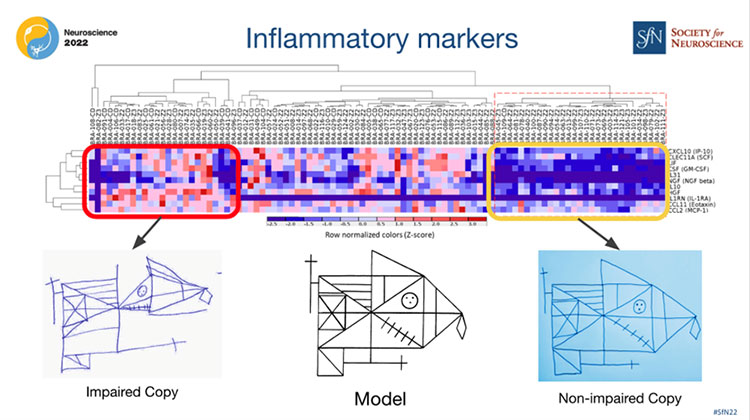

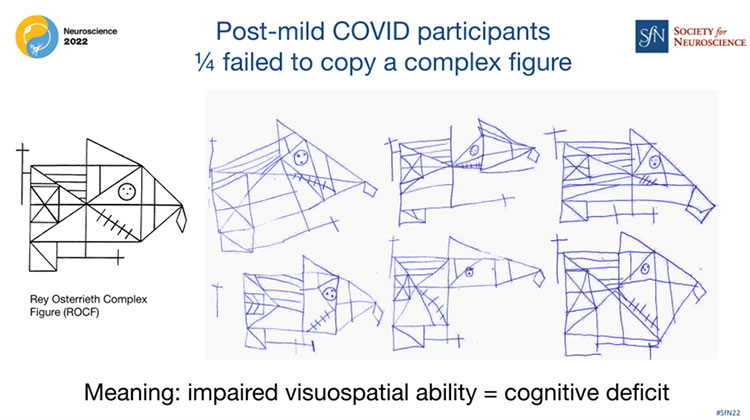

Researchers found 1 in 4 showed significant cognitive impairment in visuoconstruction skills — the visual ability to spatially reproduce designs or patterns — matching the increased levels of inflammation they were seeing on blood panels as well as in neuroimaging.

For about a quarter of participants, a test requiring them to draw a fish-like geometric figure comprised of various lines and angles proved unexpectedly challenging. Known as the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF), this neurological assessment evaluates cognitive functions such as attention, fine-motor coordination, concentration, visuospatial perception, non-verbal memory, and spatial orientation.

When one person in the first group of four or five people drew a poor copy of the complex fish figure, Romano-Silva says they initially dismissed it as an outlier. Then they noticed it was one person in every group. “It caught our attention because it’s not normal,” he says. “Usually, you’d find like 5-8% of people in the general population in this age group that would show this kind of change. But 25% was too much. So, we investigated.”

The researchers ruled out vision problems with neurological and ophthalmological exams. In addition, they conducted a battery of tests: psychiatric and cognitive assessments, and MRI and PET/CT neuroimaging. When they compared results of these tests with the drawings, they say the alterations were consistent. Those who were drawing the bad copy showed increased volume of white matter on their brain MRIs, likely due to swelling from inflammation, while their PET images showed decreased brain glucose uptake, which researchers surmised was possibly due to cells being less active and thus consuming less glucose.

Romano-Silva adds it’s “really worrying” because the group’s mean age was 38 and mostly highly educated professionals such as physicians and nurses, as recruitment took place during the initial stage of the pandemic. Interestingly, he notes participants did better on the memory and recall portion of the test, drawing the complex figure from memory better after five minutes and again after 30 minutes. “This shows it’s specialized to visuospatial organization,” Romano-Silva says. “A person looks at it and cannot organize visuospatially what they are seeing. But by memory, they are able to recruit other areas of the brain so they can make the drawing much better.”

María Díez-Cirarda of Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid and colleagues wrote in a related September 19 to the editor correspondence in Molecular Psychiatry that the research “contributes to the evidence suggesting cognitive and structural brain consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Díez-Cirarda and colleagues also mention the unusual ROCF test results that Romano-Silva had mentioned. In their correspondence, the authors highlight the finding that the patients in Romano-Silva's study revealed cognitive impairment only in visuoconstructive abilities but not in other cognitive domains such as attention or processing speed. “This was an unexpected profile of cognitive deficits,” says Díez-Cirarda, the first author of the commentary. “This is a very interesting study. This study has a large cohort of patients and performed a multimodal assessment. Research on the cognitive profile of COVID is needed to better understand the consequences of COVID-19.”

Romano-Silva agrees their results were not what they were anticipating either and hopes to further analyze and compare data in the population. In the near future, he expects a greater shift to mild COVID research. “In a few months, I think we’re going to have more data published so we can compare to see if the findings are consistent across populations.”

What About COVID-19 in Children

Until more recently, children were another population group mostly overlooked in COVID-19 research.

“Although we know that children are vulnerable to COVID-19, we still do not have a clear picture of how COVID-19 affects them in the long term,” former National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Director Anthony Fauci then said in a previous announcement of an unrelated large, long-term, prospective observational study that began in 2021 to investigate the effects of COVID-19 in 5,000 children. “In adult patients, the long-term sequelae of COVID, including post-acute COVID-19, can significantly affect quality of life. Our investigations into the pediatric population will deepen our understanding of the public health impact that the pandemic has had and will continue to have in the months and years to come.”

Silvia Hidalgo-Tobon of Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana and Children’s Hospital Federico Gómez in Mexico City and colleagues aimed to investigate post-COVID-19 in children who had severe infections. “There are no reports of long-term effects of COVID in children,” Hidalgo-Tobon says. “Because children can’t complain, it’s natural to ask ourselves what happens to them.”

Using fMRIs, the researchers compared the images of 14 children between the ages of 10 and 13 who had been hospitalized with severe COVID-19 with those of 31 healthy counterparts. They identified three areas of interest: precentral and postcentral gyrus, associated with voluntary movement and sensory processing; supplementary motor area, responsible for planning complex movements; and sensorimotor superior network, which integrates intentional movements.

They discovered the sensorimotor brain regions of children who had contracted severe COVID-19 months ago were using more resources compared with healthy children. “Our hypothesis is that if there is a dysfunction in these specific areas, other areas have to be connected that have to compensate for ideal functioning,” Hidalgo-Tobon says, remarking their findings suggest the affected areas ultimately manifested a cognitive profile similar to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). “In addition, it is important to note this activation of supplementary motor areas in a general dysfunctional way…that has an impact on executive processes.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

de Paula, J. J., Paiva, R. E. R. P., Souza-Silva, N. G., Rosa, D. V., Duran, F. L. S., Coimbra, R. S., Costa, D. S., Dutenhefner, P. R., Oliveira, H. S. D., Camargos, S. T., Vasconcelos, H. M. M., de Oliveira Carvalho, N., da Silva, J. B., Silveira, M. B., Malamut, C., Oliveira, D. M., Molinari, L. C., de Oliveira, D. B., Januário, J. N., Silva, L. C., … Romano-Silva, M. A. (2022). Selective visuoconstructional impairment following mild COVID-19 with inflammatory and neuroimaging correlation findings. Molecular psychiatry, 1–11. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01632-5

Díez-Cirarda, M., Yus, M., Matías-Guiu, J., & Matias-Guiu, J. A. (2022). Predominance of visuoconstructive impairment after mild COVID-19?. Molecular psychiatry, 1–2. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01797-z

Long-term study of children with COVID-19 begins. (2021, November 15). National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/long-term-study-children-covid-19-begins

What to Read Next

Also In COVID-19

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org