What Causes Epilepsy in Children?

- Published30 Jul 2015

- Reviewed30 Jul 2015

- Author Mary Bates

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

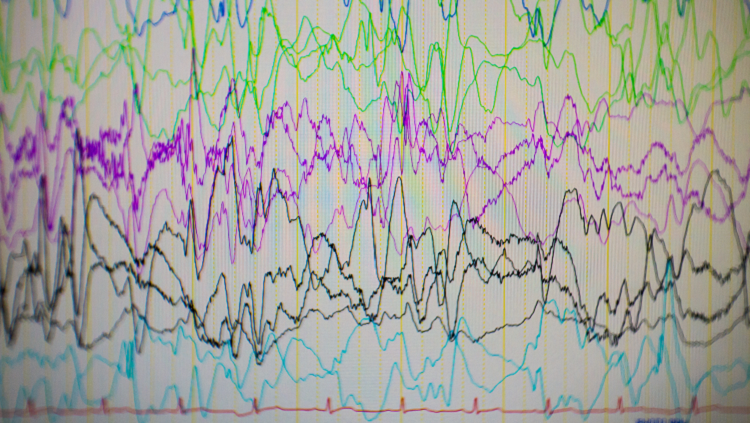

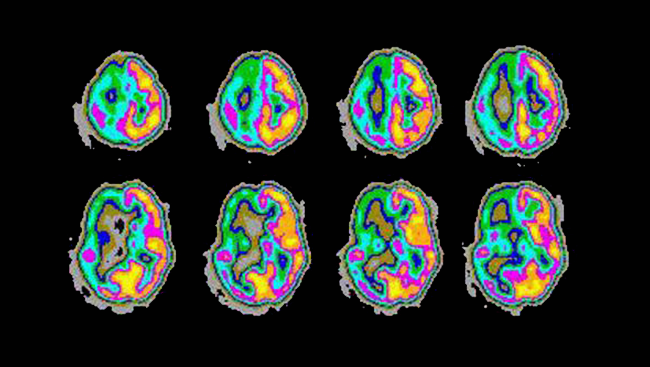

Seizures are caused by uncontrollable, spontaneous activity, and can be a debilitating condition for many people. This image shows the abnormally high activity of the right part of the brain during an epileptic seizure.

Courtesy, with permission: RME Sabbatini.

When the cells in the brain fire normally, it is like a harmonious symphony. But when someone has epilepsy, the brain experiences uncontrollable, spontaneous activity — like a trumpet playing during a violin solo. Epilepsy affects an estimated 10.5 million children worldwide, and the types and severity of the disorder can vary significantly. So what causes pediatric epilepsy, and what can be done to treat it?

Spontaneous Seizures

Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent, spontaneous seizures, and the seizures can manifest in different ways depending on which part of the brain is involved. In general, a seizure is defined as a period of abnormal, synchronous excitement of a group of brain cells. During a seizure, brain cells go into a spasm of activity, usually starting with a small group of cells and spreading to a larger area of the brain.

Some seizures, called absence seizures, cause the person to be unresponsive for a few seconds or minutes, while others, such as generalized seizures, can involve falling and convulsions.

Tallie Baram, who studies pediatric epilepsy at the University of California, Irvine, says seizures can interfere with a child’s life in many ways. “Some epilepsies can interfere with the ability of a child to pay attention in school, or they can involve brain structures that are involved in learning and memory, and these parts may not work very well,” she says. “It can also be dangerous if a child is crossing a street and suddenly loses the ability to interact with the environment or falls down to the ground.”

Causes and Prognosis

There are numerous types of epilepsy that can be due to several different causes. For example, sometimes brain damage due to trauma, such as lack of oxygen to the brain at birth or a severe brain infection, can lead to epilepsy.

“Children that are born prematurely or have very difficult births can have brain injuries that cause seizures during the first weeks of life,” says Paul Carney, a pediatric neurologist at the University of Florida. “The good news is that a lot of these children that have mild brain injury will outgrow their seizures in the first month. However, a small percentage will unfortunately go on to develop difficult-to-treat seizures that can be lifelong.”

Another cause of pediatric epilepsy is abnormal development of the brain, possibly due to maternal exposure to toxins, trauma, or an underlying genetic condition. When a genetic problem affects how the brain is formed or functions, seizures may be a visible indicator of other problems. “Seizures can be the tip of the iceberg of a serious brain disorder,” Baram says.

However, sometimes the cause of pediatric seizures is unknown. Because there is no one cause of pediatric epilepsy, there is no single prognosis. In general, 50 to 75 percent of children with epilepsy will eventually have complete seizure remission. Remission is more likely if there are no underlying neurological deficits present, seizure frequency is low, and response to anti-seizure medication is good.

Cognitive Consequences

About 20 percent of children with epilepsy have intellectual disabilities. Their epilepsy tends to persist throughout their lives with a low rate of remission.

Behavioral and psychiatric problems, such as attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, autism, depression, and anxiety, are also common in children with epilepsy.

Some current research is focused on whether seizures themselves contribute to the cognitive deficits sometimes seen in children with epilepsy. John Swann, who studies pediatric epilepsy at the Baylor College of Medicine, believes that seizures contribute to learning and memory problems.

Swann’s laboratory induced seizures in infant mice who were otherwise neurologically normal and then tested their learning and memory skills as adults. He found that mice that experienced recurrent seizures as infants demonstrated spatial learning and memory deficits as adults. Further studies using brain slices showed changes in the microanatomy of cells in the hippocampus, a brain region involved in learning and memory.

“We saw that these cells had fewer branches and fewer synapses, or connections between cells,” Swann says. “Seizures are actually preventing the normal growth of these nerve cell branches.”

Swann says there is still a lot to sort out regarding the mechanism behind this growth suppression. “It may be a protective mechanism that the brain is using to try to stop the seizures,” he says. “If you decrease the number of excitatory synapses on a nerve cell branch, then the cell will be less excitable and you might have fewer seizures.”

Treatment Options

The majority of children with epilepsy can control their seizures with anti-epileptic drugs, which act on the brain cells to make them less likely to fire.

“Medication is usually the first choice of treatment,” Carney says. “Eighty percent of children respond well to some form of medication, and the trend over the last 10 years has been to develop medications that are better tolerated and have fewer side effects.”

If seizures don’t respond to drugs, surgery to remove a small portion of the brain where the seizures originate can be considered. Seizure remission after surgery ranges from 60 to70 percent. While most children make remarkable recoveries after such surgeries, they sometimes suffer weakness on the opposite sides of their bodies from the surgery site.

Another option for medication-resistant epilepsy is vagus nerve stimulation. The vagus nerve controls body functions that are not under voluntary control, such as heart rate. In vagus nerve stimulation, a device like a pacemaker is implanted just under the left collarbone with a wire that delivers regular, mild electrical current to the vagus nerve and stimulates the brain. It is thought that this stimulation helps calm down the irregular brain activity that leads to seizures. This treatment has been shown to decrease seizure frequency by half in at least one-quarter of children.

Finally, a special diet can be considered for children who do not respond to anti-epileptic medication and who are not good candidates for surgery. The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet that mimics a fasting state and forces the body to use fat rather than carbohydrates as an energy source. While scientists don’t understand how it works, the ketogenic diet has been used for nearly 100 years to control epileptic seizures.

New Directions

What makes some pediatric epilepsies resistant to medication remains mysterious. However, new animal models and advances in neuroimaging and genetics offer new hope for treatment. Improvements in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have helped doctors detect structural brain malformations in children with drug-resistant epilepsy, making successful surgical intervention more likely.

In addition, scientists have identified many genes that contribute to different pediatric epilepsy syndromes, and they believe that medications tailored for specific genetic mutations are on the horizon.

“There are many pediatric epilepsies with which a gene hasn’t been associated yet, but it’s just a matter of time,” Swann says. “There’s reason to be hopeful. Things are changing rapidly. We’re beginning to understand in some detail what is causing epilepsy and how it’s generated, and with that we are pursuing new ways to treat it.”

While experiencing uncontrollable seizures can be catastrophic for the developing brain, both human and animal research is moving at a rapid rate to help children live seizure-free lives.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Camfield PR, Camfield CS. What happens to children with epilepsy when they become adults? Some facts and opinions. Pediatric Neurology. 51(1):17-23. (2014).

Casanova JR, Nishimura M, Swann JW. The effects of early-life seizures on hippocampal dendrite development and later-life learning and memory. Brain Research Bulletin. 0: 39-48 (2014).

Guerrini R. Epilepsy in children. Lancet. 367(9509): 499-524 (2006).

Katsnelson A, Buzsaki G, Swann JW. Catastrophic childhood epilepsy: A recent convergence of basic and clinical neuroscience. Science Translational Medicine. 6(262): ps13 (2014).

Scharfman HE. The neurobiology of epilepsy. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 7(4): 348-354 (2007).

Tolaymat A, Nayak A, Geyer JD, Geyer SK, Carney PR. Diagnosis and management of childhood epilepsy. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 45:3-17 (2015).

Wilcox KS, Dixon-Salazar T, Sills GJ, Ben-Menachem E, White HS, et al. Issues related to development of new antiseizure treatments. Epilepsia 54: 24-34 (2013).

Wilmshurst JM, Berg AT, Lagae L, Newton CR, Cross JH. The challenges and innovations for therapy in children with epilepsy. Nature Reviews Neurology. 10, 249–260 (2014).

Also In Epilepsy

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org