How Inflammation Can Drive Depression

- Published1 Oct 2025

- Author Manuela Callari

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Your immune system is your body’s built-in first responder, and inflammation is a sign it’s doing its job to fight infections and repair injuries. If you’ve ever noticed the warm, red skin around a healing cut, or felt the throb of a sprained ankle, you’ve seen inflammation in action.

But the healing fire isn’t always beneficial. Inflammation should wind down after it’s done doing damage control. Instead, sometimes it persists long after an injury or infection has resolved, sending a cascade of chemical signals into the bloodstream and ultimately wearing down the protective barrier surrounding the brain.

The disruption of this barrier upsets the brain’s delicate chemistry, leading to symptoms ranging from brain fog to depression. Understanding how persistent, low-grade inflammation breaks this protective barricade is giving researchers new insight into developing treatment options for mental health conditions, especially for people who don’t respond to traditional therapies.

A Protected Place

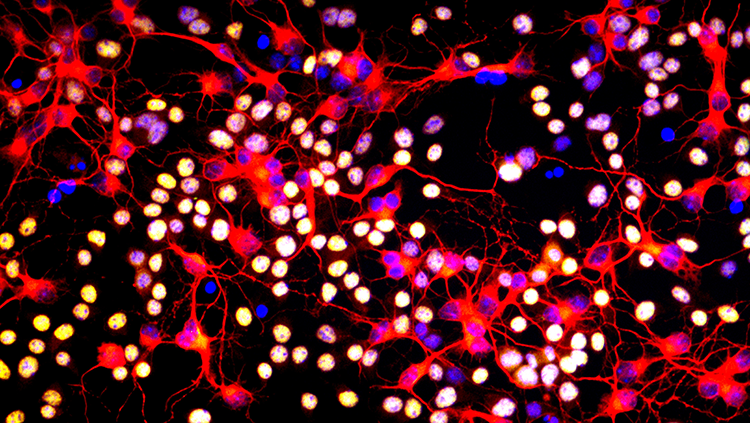

Once considered an impenetrable moat surrounding the brain, experts now understand that the blood-brain barrier (BBB), comprised of tightly packed endothelial cells, acts like a border with built in checkpoints to permit exchange between the brain and the rest of the body. The naturally leaky checkpoints allow hormones and other chemical signals to influence the brain.

However, persistent inflammation floods inflammatory proteins called cytokines into the bloodstream. Those cytokines assault the BBB, wearing it down and making it more porous.

When Stress Tears a Hole

Neuroscientist Caroline Ménard at Université Laval in Quebec City is exploring how chronic social stress impacts the BBB via an animal model that simulates bullying. Her team placed a small mouse in the same cage as a larger, more aggressive mouse for several minutes every day. The larger mouse exhibited threatening behaviors toward the smaller one including staring at it, rattling its tail, and, in some cases, physically attacking it.

Not all bullied mice reacted the same way. Some remained resilient, while others displayed behaviors akin to depression and anxiety.

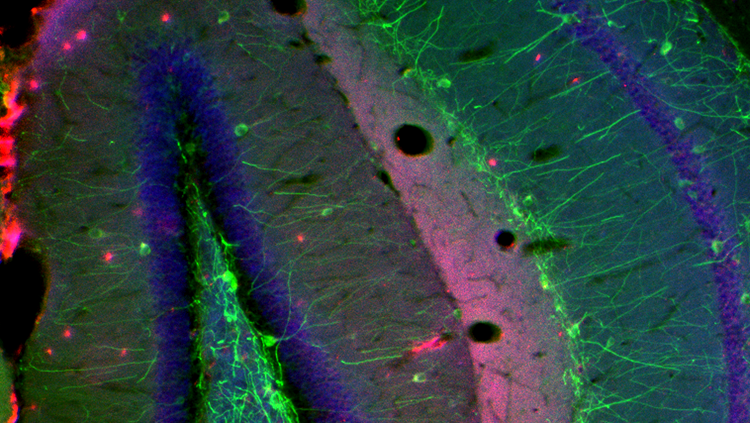

Ménard observed high cytokine levels in the blood of the stress-sensitive mice. When she examined samples taken from their brains under a microscope, she found the BBB in healthy mice was a solid line, but the barrier looked torn and compromised in the stressed animals. “Instead of having a long line, you have these tiny gaps here and there,” said Ménard. “This is where the barrier has broken.”

When cytokines sneak into the brain through these gaps, Ménard said, they can disrupt normal activity in brain circuits governing important behaviors. This could explain the subdued or frantic activity Ménard observed among the mice in her study.

Inflammation’s Influence on Behavior and Mood Disorders

Research in humans offers clues as to how chronic inflammation affects the brain, too.

A phenomenon called “sickness behavior” happens when people recovering from the flu or other infections experience “increased fatigue, less motivation to do things, depressed mood, problems with sleep,” said Valeria Mondelli, a professor of psychoneuroimmunology at King's College London. These symptoms suggest inflammatory signals lingering even after the patients had recovered from their illnesses could breach the brain's defenses and alter neural circuits governing mood and motivation.

The idea that chemical signals from the body affect the mind has pushed scientists to take a closer look at the blood-brain barrier. Ménard has studied human brain tissue from people who had depression and died by suicide. Compared to healthy controls who died from other causes, the BBB of the depressed people showed structural damage comparable to the bullied mice in her other experiment.

Breaks in the BBB can occur in various brain regions, and there’s some evidence they differ by sex. In men and in male mice, the leakiness tends to occur in the nucleus accumbens, a brain region involved in reward and motivation. In women and female mice, however, the damage is typically more apparent in the prefrontal cortex, an area related to social behavior and self-perception. The specific location of the damage is important because these brain regions govern different behaviors, offering a biological explanation for why depression sometimes manifests differently in patients of different genders.

Depressed men often report more issues with substance abuse, risk-taking, or anger,” Ménard said. “While women with depression more commonly report symptoms of social withdrawal and low self-esteem.

What Happens When the Border Fails?

Researchers believe the BBB becomes leaky due to the depletion of claudin-5, a protein which acts like mortar to hold the barrier's cells together. Ménard's team determined levels of this protein were reduced by 50% in stressed mice showing signs of depression, as well as among the people who died by suicide.

With the barrier compromised by the loss of claudin-5, the brain becomes vulnerable. Cytokines, which normally recruit immune cells to inflammation sites in the body, can flood in and guide immune cells from the body across the compromised brain barrier. Once inside, these chemical messengers trigger the brain’s own immune response, setting off a cascade of events that destabilize its chemistry.

Much of the damage occurs when these inflammatory signals alter the production and signaling ability of neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate — which in turn affects specific brain circuits regulating motivation, mood, and cognitive function. “When people are exposed to an inflammatory stimulus, the brain's motivational pathways are reduced,” said Andrew Miller, a professor and researcher in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine. This blunted response in the brain’s reward system contributes to the profound lack of motivation commonly seen in people with depression, he explained.

However, Mondelli emphasized "not everybody with peripheral inflammation [in the body] will develop mental health problems." She said pre-existing vulnerabilities, such as genetic "abnormalities in the blood-brain barrier," might explain why inflammation takes hold in the brains of some people, but not others.

Treating Inflammation to Treat the Mind

This new understanding of how cytokines breach the brain’s defenses offers new avenues to develop therapies to treat mental health conditions. If inflammation is a driver of depression for some, then anti-inflammatory medications could potentially help ease symptoms.

The challenge isn’t just finding an effective drug, but identifying the right subset of patients who will benefit from it, said Mondelli. One interesting potential group includes people who haven’t seen results after trying standard treatments. "People who are not responding to the conventional antidepressants, like an SSRI, seem to have this increased inflammation," she said.

Some researchers have turned to tocilizumab, a potent anti-inflammatory drug typically prescribed for rheumatoid arthritis, as a potential treatment for depression. Tocilizumab works by shutting down an inflammatory pathway involving a specific cytokine called “cytokine IL-6.” A research group in the United Kingdom is investigating how blocking IL-6 could improve physical symptoms of depression often linked to inflammation such as profound fatigue and sleep disturbances. They intend to publish their results later this year.

This growing field of research represents a shift towards a more biological, mechanism-based approach to mental health, moving beyond the trial-and-error strategy which has so far defined much of psychiatry, said Miller. By treating the inflammation in the body, it may be possible to mend the brain’s protective barrier and, in doing so, help heal the mind.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Chen, L., Deng, H., Cui, H., Fang, J., Zuo, Z., Deng, J., Li, Y., Wang, X., & Zhao, L. (2017). Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget, 9(6), 7204–7218. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23208

Dion-Albert, L., Cadoret, A., Doney, E., Neutzling Kaufmann, F., Dudek, K. A., Daigle, B., Parise, L. F., Cathomas, F., Samba, N., Hudson, N., Lebel, M., Signature Consortium, Campbell, M., Turecki, G., Mechawar, N., & Menard, C. (2022). Vascular and blood-brain barrier-related changes underlie stress responses and resilience in female mice and depression in human tissue. Nature Communications, 13(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27604-x

Felger, J. C., & Lotrich, F. E. (2013). Inflammatory cytokines in depression: Neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neuroscience, 246, 199–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.060

Kappelmann, N., Lewis, G., Dantzer, R., Jones, P. B., & Khandaker, G. M. (2018). Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(2), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.167

Khandaker, G. M., Oltean, B. P., Kaser, M., Dibben, C. R. M., Ramana, R., Jadon, D. R., Dantzer, R., Coles, A. J., Lewis, G., & Jones, P. B. (2018). Protocol for the insight study: a randomised controlled trial of single-dose tocilizumab in patients with depression and low-grade inflammation. BMJ Open, 8(9), e025333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025333

Ménard, C., Pfau, M. L., Hodes, G. E., Kana, V., Wang, V. X., Bouchard, S., Takahashi, A., Flanigan, M. E., Aleyasin, H., LeClair, K. B., Janssen, W. G., Labonté, B., Parise, E. M., Lorsch, Z. S., Golden, S. A., Hesmati, M., Tamminga, C., Turecki, G., Campbell, M., Fayad, Z. A., Tang, C. Y., Merad, M., Russo, S. J. (2017). Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nature Neuroscience, 20(12), 1752–1760. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0010-3

Takeshita, Y., & Ransohoff, R. M. (2012). Inflammatory cell trafficking across the blood-brain barrier (BBB): Chemokine regulation and in vitro models. Immunological Reviews, 248(1), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01127.x

Yang, J., Ran, M., Li, H., Lin, Y., Ma, K., Yang, Y., Fu, X., & Yang, S. (2022). New insight into neurological degeneration: Inflammatory cytokines and blood–brain barrier. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 15, 1013933. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2022.1013933

What to Read Next

Also In Immune System Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org