Wired for Connection, Cursed by Computers: How Social Media May Be Affecting Our Empathy

- Published1 Oct 2025

- Authors Ben Rein, Maria Tavares

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Empathy is ancient. For millennia, it has helped us understand what others feel by simply observing them. We are wired to detect signs of emotion from one another, and to take on similar emotions in response. We tear up when a loved one cries, smile when a friend laughs, and frown when a teammate hangs their head. This is empathy.

Yet, as social media platforms grow more central to how we connect, we’re spending more time sharing emotions in digital worlds through likes, shares, and comments. This shift in how we engage with one another does not go unnoticed by the molecular systems in our brains. In fact, we believe it is fundamentally altering the neurochemistry behind our interactions. We presented our case in a recent paper, arguing that our brains may not properly respond to others’ emotions in online environments. We call this new theory the “Virtual Disengagement Hypothesis.”

When people bicker with others online, they see no facial expressions and hear no tone of voice. There is no body language or eye contact, as all social cues are removed. However, neuroscience research has shown those precious social cues activate the brain areas thought to be responsible for empathy, like the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and prefrontal cortex.

This leads everyday people to commit acts of unusual hostility.

Online hate is rising, and more than half of American adults have been harassed online. In February 2024, when Award-winning American actor Julia Roberts posted a photo with her niece on Instagram, she was likely expecting a stream of heart emojis and supportive comments. Instead, she received a flood of harsh attacks. The event went viral.

The internet turned on her with a level of cruelty that left her stunned. There was nothing controversial about the photo; it was simply her appearance. In a later post, she explained how shocked she was by “the amount of people who felt absolutely required to talk about how terrible I looked.” But the madness didn’t stop there; users then began bickering with one another in the comments, tacking on an additional layer of aggression.

When we are disconnected from the emotions of others, trolling or harassing them may be neurobiologically easier. The victim’s sour emotions cannot instill a sense of distress in the harasser, allowing them to commit acts of harm guilt-free. This has serious consequences: Teens who experience online harassment are at higher risk of suicidality, and the victims of online attacks feel genuine pain. Julia Roberts reflected on this in the wake of her experience: “My feelings got hurt … and I thought, ‘God, what if I was 15?’”

If the Virtual Disengagement Hypothesis is correct, it challenges us to rethink the way we’ve shaped our digital environments. Could platforms integrate more real-time social presence, richer emotional cues, or feedback loops to make emotions more perceptible? These are important questions; but first, neuroscience must catch up to our rapidly evolving communication technologies to properly test this hypothesis.

In neuroimaging studies, lab participants are typically isolated in fMRI machines and shown curated videos or static images to identify the accompanying brain activity. However, to our knowledge, studies have yet to present participants the frenetic, unique experience of social media. The tools exist, but the experiments haven’t been run.

Considering nearly 63% of the world’s population uses social media and spends over 10% of their time there, it’s shocking neuroscience has failed to search for these answers. These virtual interactions comprise approximately 6.5% of global attention daily, and yet we understand little to nothing about how they engage our brains. We believe it’s time to find these answers.

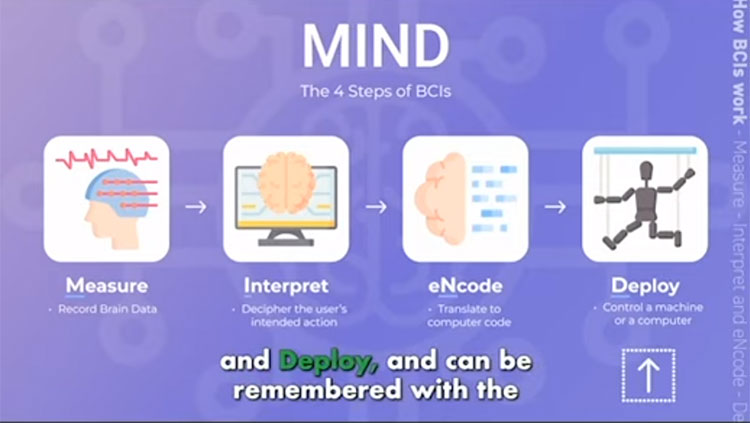

In our 2024 article, we urge neuroscience to catch up to our evolving world. Neuroscientists should develop tests that simulate social media environments and incorporate neuroimaging to understand how the brain functions in virtual interactions. These studies could examine the importance of various social cues and sensory inputs to identify which matter most. How does the brain react to text posts on X, versus video posts on TikTok? Does the brain respond differently to live-streams versus pre-recorded videos? Does hostility rise in response to specific content formats, and can we trace these behaviors to differences in brain activity? The research must start to understand how brains function in a world that favors swipes, not eye contact.

This is especially important considering what neuroscience research shows: Social interaction is fundamental to our health and well-being. As I explain in my upcoming book, “Why Brains Need Friends,” we are wired for connection, and when we fail to find it, we face legitimate threats to our mental and physical health. Isolation increases the risk for conditions like dementia and heart failure, and lonelier people are at higher risk of death by any cause. Is a healthier social media environment the answer? It remains to be seen, but one thing is for sure: Our current toxic online culture is doing no good for our already-isolated brains.

There are early hints of hope. Studies have shown empathy-based counterspeech can reduce hate online. But more is needed. To build platforms that foster empathy rather than erode it, we must identify which design features engage the brain’s social circuits and which fail to. In a world where billions of people interact online every day, understanding how the brain navigates virtual relationships is not optional; it’s urgent. This demands prioritization in social neuroscience. Because a new virtual world isn’t around the corner; it’s already here.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

ADL Center for Technology & Society. (2023). Online Hate and Harassment: The American Experience 2023. Anti-Defamation League. https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/2023-12/Online-Hate-and-Harassmen-2023_0_0.pdf

Chan, S. W. Y., Sussmann, J. E., Romaniuk, L., Stewart, T., Lawrie, S. M., Hall, J., McIntosh, A. M., & Whalley, H. C. (2016). Deactivation in anterior cingulate cortex during facial processing in young individuals with high familial risk and early development of depression: fMRI findings from the Scottish Bipolar Family Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(11), 1277–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12591

Dixon, S. J. (2025). Daily time spent on social networking by internet users worldwide from 2012 to 2025 (in minutes). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/433871/daily-social-media-usage-worldwide/

Donate, A. P. G., Marques, L. M., Lapenta, O. M., Asthana, M. K., Amodio, D., & Boggio, P. S. (2017). Ostracism via virtual chat room-Effects on basic needs, anger and pain. PloS One, 12(9), e0184215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184215

Hangartner, D., Gennaro, G., Alasiri, S., Bahrich, N., Bornhoft, A., Boucher, J., Demirci, B. B., Derksen, L., Hall, A., Jochum, M., Munoz, M. M., Richter, M., Vogel, F., Wittwer, S., Wüthrich, F., Gilardi, F., & Donnay, K. (2021). Empathy-based counterspeech can reduce racist hate speech in a social media field experiment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 118(50), Article e2116310118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116310118

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

John, A., Glendenning, A. C., Marchant, A., Montgomery, P., Stewart, A., Wood, S., Lloyd, K., & Hawton, K. (2018). Self-Harm, Suicidal Behaviours, and Cyberbullying in Children and Young People: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4), e129. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9044

Kuiper, J. S., Zuidersma, M., Oude Voshaar, R. C., Zuidema, S. U., van den Heuvel, E. R., Stolk, R. P., & Smidt, N. (2015). Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 22, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006

Liang, Y. Y., Chen, Y., Feng, H., Liu, X., Ai, Q. H., Xue, H., Shu, X., Weng, F., He, Z., Ma, J., Ma, H., Ai, S., Geng, Q., & Zhang, J. (2023). Association of Social Isolation and Loneliness With Incident Heart Failure in a Population-Based Cohort Study. JACC. Heart Failure, 11(3), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2022.11.028

Petrosyan, A. (2025). Number of internet and social media users worldwide as of January 2024 (in billions). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/

Rein, B. (2025). Why Brains Need Friends. Penguin Random House. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/761227/why-brains-need-friends-by-ben-rein-phd/

Tavares, M., & Rein, B. (2024). The virtual disengagement hypothesis: A neurophysiological framework for reduced empathy on social media. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 24(6), 965–971. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-024-01212-w

Vogels, E. A. (2021). The State of Online Harassment. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

What to Read Next

Also In Tech & the Brain

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org