Why the Brain Loves Stories

- Published4 Mar 2021

- Author Calli McMurray

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Erin Barker walks onto the small stage. Murmurs still ripple through the crowd as she clutches the microphone and starts speaking. But the conversations don’t last long. A thick silence pours over the audience. One sentence brings laughter, and the next sends a palpable shock. Barker’s audience is rapt, wholly absorbed in her narrative.

The brain is a story addict, always on the hunt for a character. If you’ve listened to hours of podcast episodes or stayed up until 3 a.m. binge-watching a TV series, you know the power of good narrative.

For a compelling storyteller to hold your attention, they must achieve narrative transportation, “that delicious feeling of being sucked into a story world,” said Liz Neeley, former executive director of Story Collider, a storytelling nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Story Collider hosted live storytelling events in crowded, intimate settings like bars and coffee shops. People took the stage and shared personal stories about their experiences with science. Now they do this online.

Storytellers, like Barker, can tell right away if they’ve achieved narrative transportation. “We're so used to getting that immediate feedback from our live audience,” says Barker, Story Collider’s artistic director. “Being able to feel the applause, even the tense silences when we're at a very dramatic point in the story.”

The pandemic may have moved the in-person, oral-storytelling tradition to virtual spaces, but it hasn’t changed the social nature of the experience. Whether in a group of squealing friends around a campfire or hushed tones over the phone, a story — compared to facts-only delivery — triggers stronger emotional responses, making you more likely to remember information and change your attitudes or behaviors.

Stories Connect People — And Their Brains

The act of sharing a story is powerful. So much so that it synchronizes the brain activity of the teller and the listener. “Your brain responses while listening become coupled to my brain responses, and slowly they become more similar to my brain responses,” said Uri Hasson, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Princeton University.

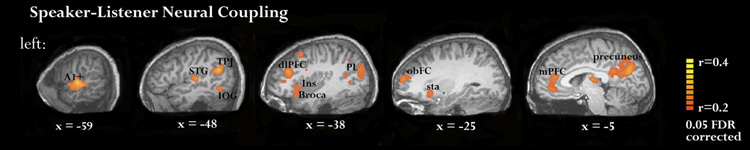

In one study, Hasson’s team compared the brain activity of a storyteller with a listener using fMRI. The listener’s brain activity mirrored that of the storyteller’s with just few second’s delay. The synchronized activity appeared not only in basic language processing areas but also in high-level networks involved in understanding meaning. The level of synchronized activity in one such network — the default mode network — predicted the success of the communication. “The stronger the coupling, the better the understanding,” said Hasson.

Beyond the connection between storyteller and listener, creating stories recruits brain regions involved in social interactions. Part of the mentalizing network — a group of brain regions employed to predict the motivations, emotions, and beliefs of other people — also comprises a “narrative hub” in the brain activated by telling a story. In one study, researchers at McMaster University measured the brain activity of artists while they shared the contents of brief headlines through one of three mediums: words, drawings, or gestures. The headlines described a character completing an action, such as “Surgeon finds scissors inside of patient.” Across all three storytelling mediums, story production activated several brain regions from the mentalizing network.

This means even though they weren’t asked to, participants focused on the characters and their mental states. While telling a story, the brain attends more to what a character is thinking or feeling during an event than the sequence of events itself.

In a way, focusing on character might set stories up so we can “practice” social skills and beef up underlying brain networks. In a study available online that has not yet gone through peer review, a pair of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Radboud University measured activity in the mentalizing network while people listened to stories. The participants also completed a survey about their typical reading habits. People that read more fiction had higher levels of synchronized activity between mentalizing regions — a sign that their brains are better at processing the mental states of others. Engaging with narratives may be a kind of exercise for social cognition, in the same way that hitting the gym exercises muscles.

Stories as Sensemaking

The social component of stories may explain why they emerged in human evolution. Stories exist across cultures and time, bringing people together and helping them make sense of the world. They serve as a “collective sensemaking process,” said Neeley, “Stories are the ways in which we knit together events, that we postulate about causality, that we resolve ambiguity. We identity who the heroes are and who the villains are.”

Listening to stories can also help people make sense of personal emotions and situations. When Reyhaneh Maktoufi, a Civic Science Fellow in misinformation at NOVA, struggled to get answers about an unexpected medical issue, she turned to the Story Collider podcast, where she also works as a producer. She listened to an episode about a family dealing with the aftermath of a car crash and felt a flood of cathartic emotions. “That's what I needed to relate to. I had pain and I needed to hear pain and how someone deals with it,” said Maktoufi. “We need those stories where people can [think], ‘That's what I'm feeling right now.’”

Using stories to wrestle with difficult emotions and process confusing events helps people regain a sense of control when they need it most. Yet this combination can become a breeding ground for conspiracy theories that often crop up after major events or societal changes, including assassinations, terrorist attacks, and disease outbreaks like the COVID-19 pandemic. Conspiracy theories aren’t new: even the black plague was blamed on religious punishment rather than contagious pathogens.

The strengths of storytelling as a communication medium — transportation, emotional responses, improved recall — can easily be misused. “The scary thing is that stories are actually very effective ways to spread misinformation,” said Maktoufi. Plus, some of the best conspiracy theories and propaganda employ skilled narrative techniques. “When you're really transported in a story, you're less likely to actually spot lies and falsehoods.”

Responsible Storytelling

This creates a fine line between sharing your unique experiences and spreading misinformation. “I think the line is passed when you talk about your personal experience of something happening to me, something I felt and saying, ‘This is the truth about something,’” said Maktoufi. But the potential to abuse the power of storytelling should not stop people from using it. “The truth is it’s a tool,” said Neeley. “It’s like a hammer. You can build houses or break kneecaps; it’s just about how you apply this powerful tool.”

When you tell your own stories, focus on how you felt and what you experienced, rather than making broad statements about the world. And when you listen to stories, “Get into the habit of pausing for a moment and thinking of where the story is coming from,” said Maktoufi, as well as what the speaker’s motivations may be. These extra steps are worth the effort, as authentic and ethical storytelling has the potential to ease the emotional burden of tragedies like the COVID-19 pandemic. “We need to keep telling these stories because they are the ways we connect with the world. They are the ways we share a part of our feelings,” said Maktoufi. “We see it outside in the world and it calms us down. It helps us understand what we're going through.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

1. Yuan, Y., Major-Girardin, J., & Brown, S. (2018). Storytelling Is Intrinsically Mentalistic: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Narrative Production across Modalities. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 30(9), 1298–1314. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01294 https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.1162/jocn_a_01294

2. Coe, K., N.E. Aiken, and C.T. Palmer. (2006) Once Upon a Time: Ancestors and the Evolutionary Significance of Stories. Anthropol. Forum. 16, 21–40. doi:10.1080/00664670600572421. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00664670600572421

3. Gerrig, R. J. (1993). Experiencing narrative worlds: On the psychological activities of reading. New Haven: Westview. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-98290-000

4. Bietti, L.M., Tilston, O. and Bangerter, A. (2019), Storytelling as Adaptive Collective Sensemaking. Top Cogn Sci. 11, 710-732. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12358

5. Stephens, G. J., Silbert, L. J., & Hasson, U. (2010). Speaker-listener neural coupling underlies successful communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(32), 14425–14430. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1008662107

6. Mar, R. A. (2018). Stories and the Promotion of Social Cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417749654

7. Douglas, K.M., Uscinski, J.E., Sutton, R.M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C.S. and Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Political Psychology, 40, 3 - 35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

8. Willems, R. M., & Hartung, F. (2020). Amount of fiction reading correlates with higher connectivity between cortical areas for language and mentalizing. BioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.08.139923v1

What to Read Next

Also In The Arts & The Brain

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org