Your World In 3-D, No Glasses Needed

- Published10 Sep 2019

- Author Charlie Wood

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

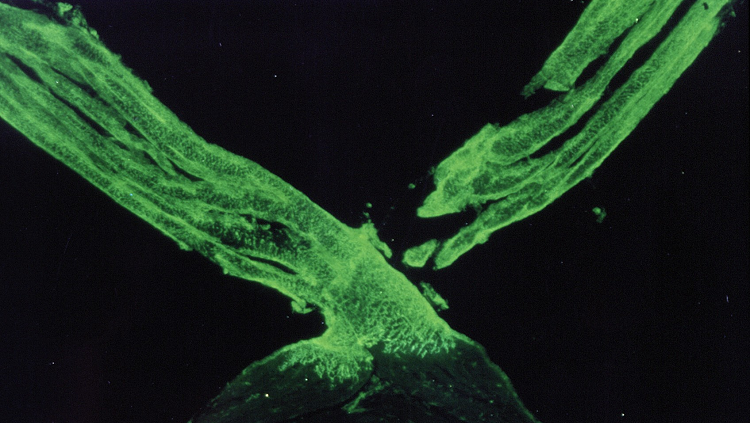

The scene in front of you may look smooth, but that’s a post processing trick. The raw footage from each eye gets split vertically by the optic chiasm (from “crossing,” in Greek), seen here in a zebrafish.

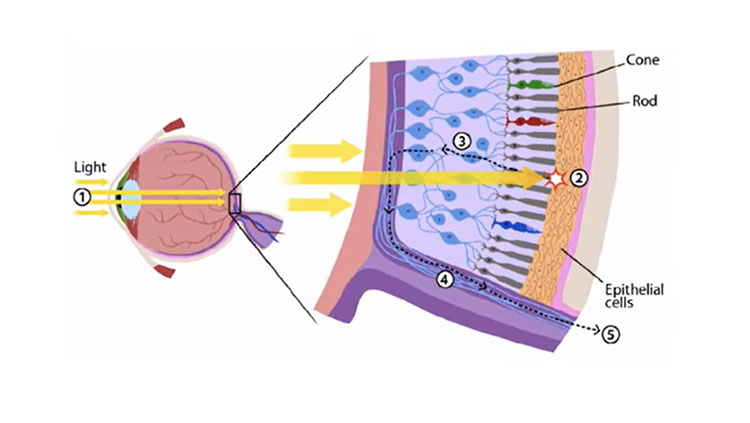

First, a bundle of axons called the optic nerve carries visual information whole from each eye back into your head. If there is damage from a tumor or trauma at this point, it could leave one entire eye blind. But then the chiasm shuffles things around to create a clear picture for you.

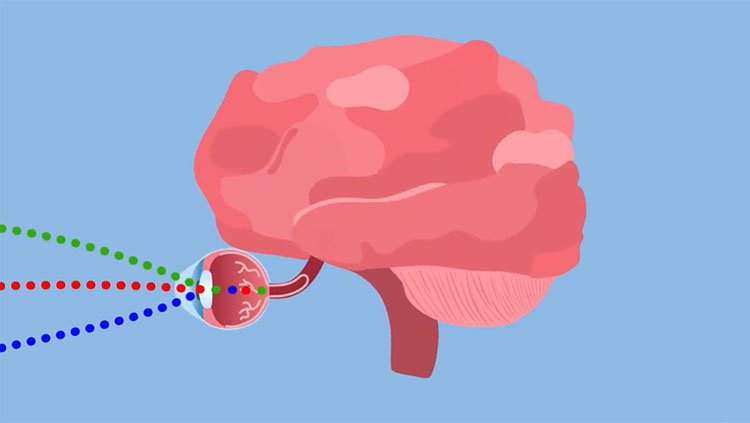

Data from the inside of your eye, nearest your nose, pass straight through the optic chiasm to the opposite side of your brain, while information from the outer halves of your eyeball bends outward to stay on the same side. The upshot is that each hemisphere gets two perspectives on the same area — one from each eye — that it can then combine to see depth. The brain hemisphere that processes sights on, say, the left side also happens to be the half that mainly controls the left hand — an intriguing coincidence that leads some researchers to speculate that depth perception and fine hand movement evolved together.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Dingman, M. (November, 2018). Optic Nerve Deficits. Neuroscientifically Challenged. Retrieved from https://neuroscientificallychallenged.com/optic-nerve-deficits

Larsson, M. (2013). The optic chiasm: a turning point in the evolution of eye/hand coordination. Frontiers in Zoology, 10(1), 41–41. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-10-41

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org