Oxytocin: Bonding, Birth, and Trust

- Published24 Oct 2014

- Reviewed24 Oct 2014

- Author Caitlin Kirkwood

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

When researchers began searching for clues about how the brain signals to the body that the time has come to give birth, they had no way of knowing doing so would guide them to a hormone involved in social behaviors like attachment, trust, and empathy. Scientists are hopeful that studies of the brain chemical oxytocin will lead to a better understanding of disorders marked by social dysfunction, such as autism.

Identifying a safer way to induce labor led to understanding brain cell communication and influences on social behavior

From dictating body growth to regulating hunger and thirst, the brain plays an active role in numerous body functions. In the 20th century, researchers studying cell communication identified the signals the brain sends the body when the time comes to deliver a baby. This discovery forever changed medicine and later had surprising implications for understanding the brain's role in social behavior.

Discovery of brain chemical improves labor outcomes

In the early 1900s, there were limited options for women whose pregnancies posed sudden risks to them or their unborn children. Existing methods of labor induction often led to infection, endangering the health of the mother and child.

British physiologist and pharmacologist Sir Henry Dale studied chemicals that communicate throughout the body, which eventually led him to discover the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize. But in 1906, he uncovered the body's natural signal for stimulating labor.

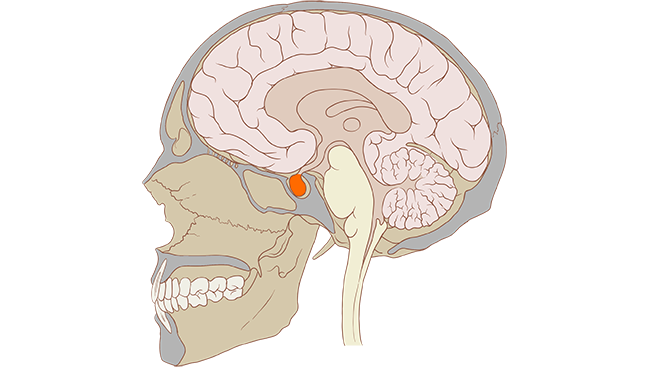

The posterior pituitary contains nerve endings from the hypothalamus — a brain structure that produces many different hormones and brain chemicals — which helps to store and release these hormones. When Dale injected the brain chemicals from the posterior pituitary into pregnant cats, dogs, and guinea pigs, he discovered he could stimulate uterine contractions without causing harmful side effects.

Dale later isolated the active brain chemical that was behind the contractions — a hormone he named oxytocin (derived from the ancient Greek words for “swift birth”). Additional studies soon revealed oxytocin was also responsible for the release of milk necessary for nursing.

Revolutionizing a medical procedure

As interest in using oxytocin to induce labor in women grew, so too did the desire to better understand the hormone. American biochemist Vincent du Vigneaud was studying the structure of proteins in the early 1950s when he became interested in oxytocin. After successfully determining its chemical structure, he found a way to manufacture synthetic versions of oxytocin in the laboratory.

Today, synthetic forms of oxytocin, like Pitocin, are used all over the world to facilitate labor and manage postpartum hemorrhage. For his work, du Vigneaud was awarded the 1955 Nobel Prize in Chemistry His research also laid the foundation for yet more discoveries about oxytocin's role in behavior.

Brain hormone's role in social behaviors

Knowing the role of oxytocin in birth and nursing led researchers of the 1970s and 1980s to begin asking questions about the brain hormone's involvement in the development of relationships that form between a mother and child.

Shaping maternal behavior

In general, virgin female rats do not like newborn pups; some prefer to avoid the pups, while others aggressively attack. Yet, as soon as a female mothers her own litter, this hostile behavior subsides.

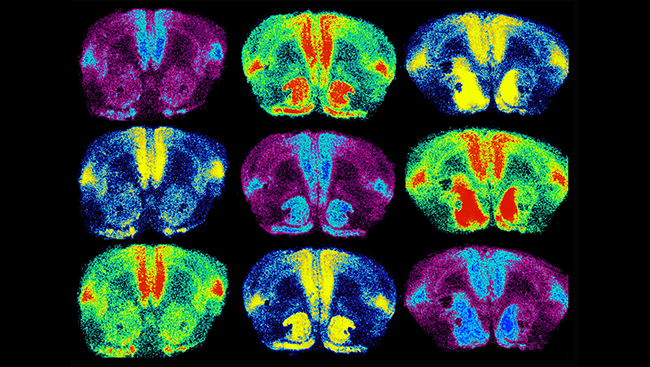

To determine if oxytocin plays a role in this switch, scientists administered the hormone into the brains of virgin females before placing them in the presence of a newborn litter. Within hours, most of the virgins went from avoiding the pups to building a nest, grooming them, and carrying them around as if they were their own. In contrast, when researchers blocked oxytocin from binding to its receptors in the brains of new rat mothers, the animals were slower to respond to their young, and, in some cases, they ignored them all together. These and other studies support the role of oxytocin in maternal behavior.

A molecular matchmaker

In the 1990s, researchers became curious about what role, if any, oxytocin plays in the bonds that form between couples. To test this, they turned to the prairie vole — a rodent that, unlike most, mates for life. In voles, sex triggers the release of oxytocin, which appears to cement bonds between adults. In one study, scientists discovered that unlike untreated voles, voles that received oxytocin preferred spending time with voles of the opposite sex that were familiar rather than novel.

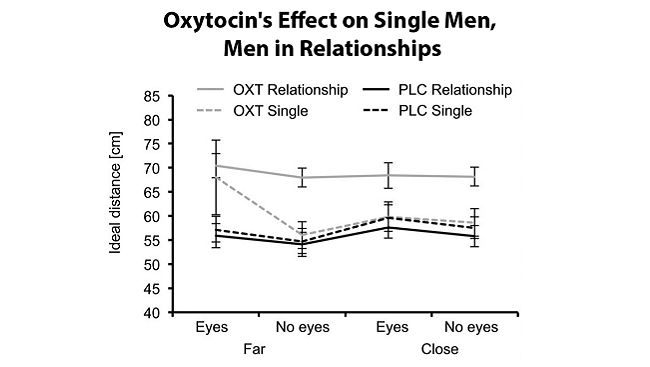

These and other animal studies led scientists to explore the role oxytocin may play in monogamous human relationships. In one such study, researchers administered oxytocin nasal spray to a group of healthy men before introducing them to an attractive female. They found that those in monogamous relationships chose to stand farther from the woman than did single men who received the hormone and those who received a placebo. These findings suggest that oxytocin may help promote fidelity within monogamous relationships.

New clues about social disorders

Double-edged actions

As evidence for oxytocin’s role in establishing and maintaining relationships grew, new studies focused on the effects of the hormone on other social behaviors.

Neuroeconomic studies revealed that investors given oxytocin are more willing to loan small amounts of money to strangers. While such studies suggest that oxytocin may be involved with promoting trust, more recent studies paint a far less rosy picture. For instance, while people given oxytocin may be more empathetic to people they consider like them, they fail to display the same level of empathy toward outsiders. In fact, one study found that participants given oxytocin express stronger biases against people outside their group than those who did not receive the hormone.

Potential role in developmental disorders

Due to oxytocin's nuanced role in social behaviors, scientists have started to look at the role of the hormone in disorders characterized by abnormal social interactions.

One such disorder is Williams syndrome, a rare condition that, in addition to cognitive deficits, causes people to be overly trusting and friendly. A recent preliminary study in a small group of participants showed those with the disorder had three times more oxytocin circulating in their blood than did other study participants, suggesting the social aspects of Williams syndrome may be due to dysfunction of the oxytocin system.

In contrast to Williams syndrome, autism spectrum disorders are marked by social deficits. Scientists recently traced differences in the gene that makes oxytocin receptors to autism risk. While several studies have found that a single dose of oxytocin given to children and adults with autism results in an increased willingness to interact socially, much remains unknown about the long-term effects of chronic oxytocin administration, particularly in the developing brain.

The story of the surprising discovery that a hormone first identified for its effect on birth plays an important role in social behavior and neurodevelopmental disorders demonstrates promising new avenues for progress on disorders that cause untold family hardship and significant health care costs. It also highlights the value of cross-disciplinary research and continued investments in basic science research in fields as varied as chemistry, biology, physiology, economics, and sociology.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Carson DS, Guastella AJ, Taylor ER, McGregor IS. A brief history of oxytocin and its role in modulating psychostimulant effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 27(3): 231-247 (2013).

Cho MM, DeVries AC, Williams JR, Carter CS. The effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on partner preferences in male and female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Behavioral Neuroscience. 113 (5): 1071-1079 (1999).

Dai L, Carter CS, Ying J, Bellugi U, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, et al. Oxytocin and vasopressin are dysregulated in Williams syndrome, a genetic disorder affecting social behavior. PLoS ONE. 7(6): e38513 (2012).

De Drue C, Greer L, Handgraff M, Shalvi S, Kleef G, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science. 328, 1408-1411 (2010).

De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Van Kleef GA, Shalvi S, Handgraaf MJ. Oxytocin promotes human ethnocentrism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108(4):1262-6 (2011).

Gordon I, Wyk V, Bennett RH, Cordeaux C, Lucas MV, et al. Oxytocin enhances brain function in children with autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (52) 20953-20958 (2013).

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs Z, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 435(7042): 673-676 (2005).

LoParo D, Waldman ID. The oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is associated with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry. (2014).

Monk C, Spicer J, Champagne FA. Linking prenatal maternal adversity to developmental outcomes in infants: the role of epigenetic pathways. Development and Psychopathology. 24(4):1361-76 (2012).

Nagasawa M, Okabe S, Mogi K, Kikusui T. Oxytocin and mutual communication in mother-infant bonding. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6 (2012).

Nowak R, Keller M, Lévy F. Mother-young relationships in sheep: a model for a multidisciplinary approach of the study of attachment in mammals. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 23(11): 1042-1053 (2011).

Oxytocin and sexual behavior. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 16(2):131-44 (1992).

Pedersen CA, Prange AJ Jr. Induction of maternal behavior in virgin rats after intracerebroventricular administration of oxytocin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 76(12):6661-5 (1979).

Rilling JK, Young LJ. The biology of mammalian parenting and its effect on offspring social development. Science. 345(6198): 771-776 (2014).

Ross HE, Young LJ. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 30(4): 534-547 (2009).

Scheele D, Striepens N, Gunturkun O, Deutschlander S, Maier W, et al. Oxytocin modulates social distance between males and females. Journal of Neuroscience. 32(46): 16074-16079 (2012).

van Leengoed E, Kerker E, Swanson HH. Inhibition of post-partum maternal behaviour in the rat by injecting an oxytocin antagonist into the cerebral ventricles. Journal of Endocrinology. 112(2):275-82 (1987).

Also In Genes & Molecules

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org