What Ants Teach Us About the Biology of Social Behavior

- Published10 Feb 2026

- Author Bella Isaacs-Thomas

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

In tropical forests from the southern United States into South America, armies of leafcutter ants toil relentlessly, slicing up leaves and hauling them to massive subterranean colonies. Whereas most ants are scavengers or predators, leafcutter ants are farmers, and their cargo is the substrate on which they grow gardens of fungus for food. The effort relies on each ant performing a specialized role — from cutting leaves, to protecting the column of ants to and from the colony, to cultivating fungus. With each role comes a specific body type, from large soldier ants with huge mandibles to small minor ants tending to the colony’s young.

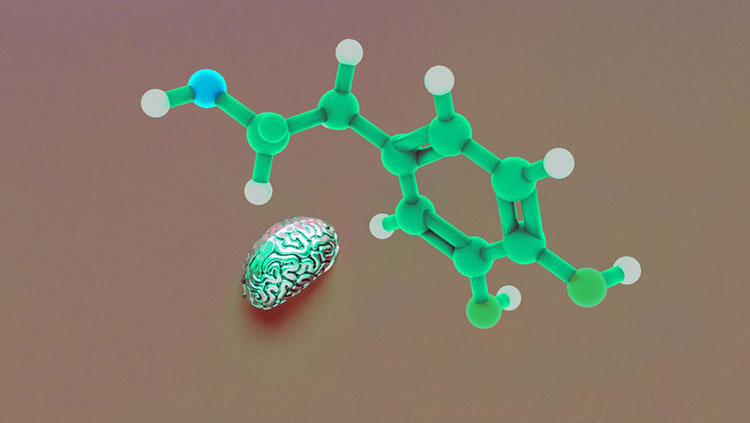

Despite radically different roles and appearances, leafcutter ants are nearly genetically identical to each other. They perform their roles in part as a response to neuropeptides — molecules produced by the body that can directly influence behavior. An international group of researchers found that by tweaking the levels of two neuropeptides in the brains of living ants, they could alter their behavior, causing the ants to functionally switch jobs. They published their study results in the scientific journal Cell.

“Now you've got this big female soldier with her big mandibles going over and very delicately picking up the pupae and moving it over to the fungus,” said Shelley Berger, who is the senior author of the paper and directs the Epigenetics Institute at the University of Pennsylvania.

Same Genes, Different Jobs

Like leafcutter ants, the individual cells in our bodies carry the same basic genome, or genetic information packaged into DNA. Despite this fundamental commonality, individual cells across our bodies perform markedly different functions, Berger explained.

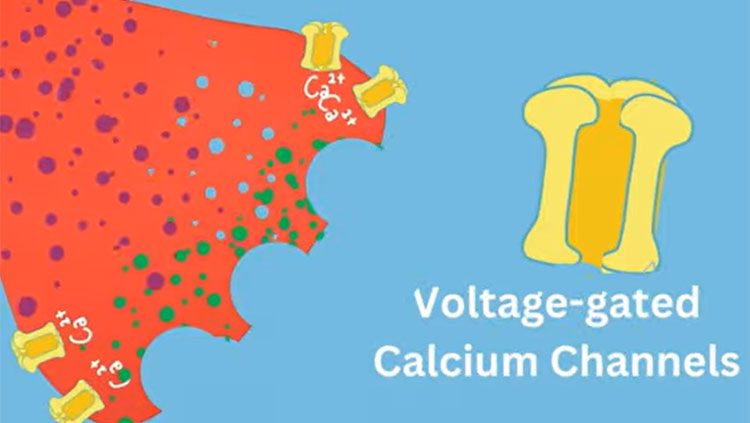

Our cells, and ants, take on different jobs based on influences coming from the body or from the environment. Neuropeptides are one such source of influence. They act on the switches and dials of each gene, turning them on and off or up or down. The resulting variations in gene expression determine their unique identities.

In other words, the genome is like a xylophone, and the external forces controlling the mallets can play countless songs without changing the construction of the instrument.

Berger’s team selected two neuropeptides particularly important to shaping leafcutter ant behavior — crustacean cardioactive peptide (CCAP) and neuroparsin-A (NPA). Upping CCAP in the soldiers prompted them to start harvesting leaves, while decreasing NPA led them to start caring for the colony’s youngest members.

The researchers took several approaches to manipulate the levels of the two neuropeptides. They directly injected CCAP into the ants’ brains, and they turned down the dial on the gene that makes NPA. Going into their experiment, the team proposed that CCAP drives leaf cutting behavior, and that high levels of NPA repress caretaking behavior, so they hypothesized tinkering with each neuropeptide level would encourage those actions.

To observe the results of their manipulation on a cellular level, they examined the real-time gene expression of cells within individual ant brains. This gene expression is like the noise generated from tapping a mallet on a xylophone bar, and the resulting "song" is called the transcriptome. By altering the neuropeptide levels in one ant — like when they prompted soldiers to begin demonstrating caretaking behavior — the researchers changed its brain transcriptome to mirror that of a totally different subcaste.

“We found that by lowering NPA, we had switched the brain transcriptome from the soldier type — so let's say like a liver cell — and changed it into a nurse transcriptome, [or] completely different cell type, like a brain cell,” Berger said. This shift was semi-permanent; the soldier ants continued to demonstrate alternate behavior for several weeks before reverting back to their original role.

How Neuropeptides Affect Us

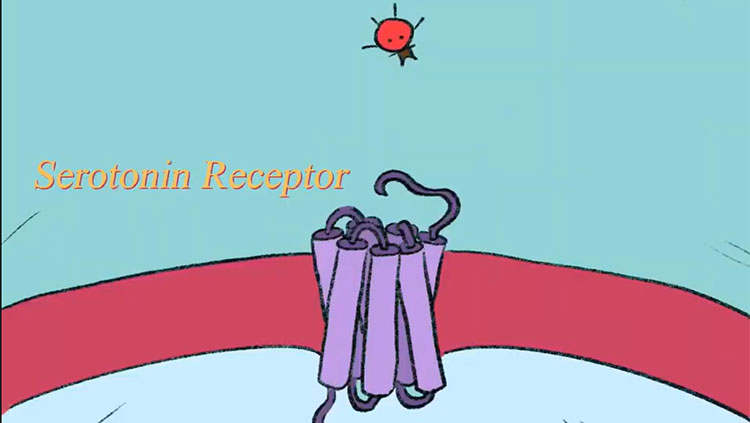

Ants are of specific interest to scientists because they live in highly organized societies with stratified workforces, but all animals can help shed light on the molecular forces influencing behavior. In his research on neuropeptides, Maurice Elphick, a professor of physiology and neuroscience at Queen Mary University of London, focuses on echinoderms like sea urchins and starfish. Although they perform multiple functions in the body, neuropeptides are notable for their ability to quickly and dramatically alter conscious experiences.

“You could think of them as being molecules that shape the way we feel,” Elphick said.

Many neuropeptides are found in multiple species. Elphick noted CCAP was first identified in crabs for its ability to excite the heart, and it was later linked to feeding behavior in fruit flies. Oxytocin, perhaps one of the more famous neuropeptides, is crucial for regulating mating behavior across the animal kingdom, from humans to nematodes.

Elphick said he found Berger’s team’s findings convincing and interesting, adding new evidence on how these molecules change animal behavior. He pointed out that identifying where in the brain neuropeptides and the receptors they latch on to are located is crucial to understanding their roles, though this paper didn’t dig into those details. Berger and her colleagues plan to analyze neural circuitry differences across ant subcastes, and how neuropeptides act on those systems, in future research.

For Berger, ants are fascinating because of parallels between their societies and ours. Understanding how those social structures work, she said, could offer us deeper insight into our own.

She noted the United States has historically invested in various research efforts, including ones like these, but that the promise of federal resources is increasingly insecure due to shifting policies. Her team’s research was supported by several institutions, including the National Institutes of Health and the Human Frontier Science Program.

“[Funding is] in danger right now, and scientists are trying to make pitches about why it's interesting,” Berger said. “People ask ‘Why would you study ants? Crazy, stupid little ants?’ Well, maybe we can understand something about humans.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

What to Read Next

Also In Genes & Molecules

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

.jpg)