Learning About Language From Birdsong

- Published27 Apr 2017

- Reviewed27 Apr 2017

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Songbirds are one of the few known species who learn to speak (or sing) like we do. That makes them the perfect case study to learn about the origins of language in the brain.

Animation by Matt Wimsatt. Zebra finch audio recordings provided by Heather Williams, Williams College. Special thanks to Fernando Nottebohm, Rockefeller University.

Have a question about what you just watched in our animated video? Submit Your Question

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

How do we go from this [audio: baby babbling] to this [audio: toddler speaking]? Language is one of the defining features of being human, but how are we able to acquire it?

Many animals make sounds - lions roar [audio: lion roaring] and frogs croak [audio: frog croaking]. But most don't learn to make these the same way we learn language. As babies, we listened to people around us speaking and learned how to imitate those sounds. Humans, dolphins, whales, and some bats are the only mammals that learn to vocalize this way. But some species of songbirds also employ this kind of vocal learning.In fact, songbirds have a lot to teach scientists about vocal learning. By studying how songbirds learn their tunes, [audio: songbird] we are discovering how our own brains are organized and how we acquire language.

Research in songbirds like zebra finches has unearthed important clues about the brain circuits underlying vocal learning. Native to Australia, the zebra finch is a stocky little songbird. With bright orange cheeks and black and white striped feathers adorning his breast, the male zebra finch is an ostentatious entertainer, belting out tunes in hopes of impressing a female. But he wasn’t born with such a beautiful singing voice — he acquired it through learning and practice.

Zebra finches begin their vocal training with indiscriminate chirping. After listening to adult finches, they slowly progress to singing full tunes, just like babies progress from babbling to uttering complete sentences by about 3 and a half years of age. And just like in human babies, there’s a critical window of time during which a young finch must hear adults sing so he can learn to make those same sounds.

Whether it’s human language or birdsong, producing sounds is a motor skill. Anything that requires you to consciously move your muscles is a motor skill, like running or swinging a bat. Even getting out of bed in the morning and then walking downstairs. And motor skills, as we all know, take practice. It’s a process of trial and error that requires sensory feedback from—wait, let’s back up a little bit.

Outside of your brain and spinal cord there are 2 kinds of nerves: motor nerves and sensory nerves. Extending from the spinal cord, motor nerves signal your muscles to move. Sensory nerves, on the other hand, send information about sensation — touch and position to name a few — back to your brain.

Motor skills — like mastering a wicked backhand in tennis, playing the piano without missing a note, or learning how to speak — depend on this kind of sensory feedback so we can adjust and perfect our performance through trial and error.

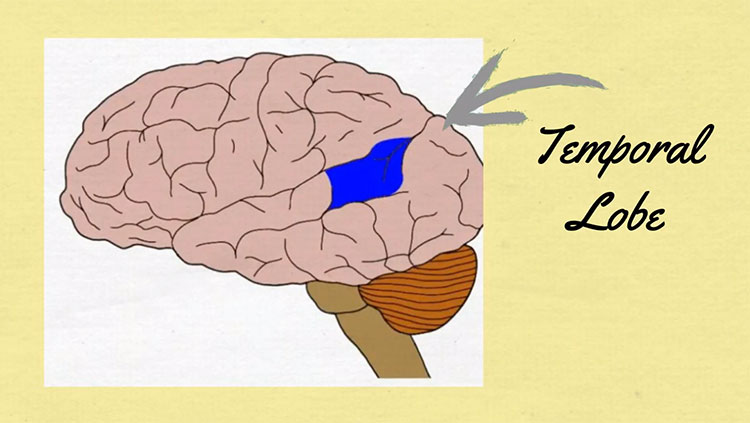

Key to this process of trial and error is a group of brain structures called the basal ganglia. It receives motor and sensory information from an area of the brain called the cerebral cortex which is responsible for planning movement among many other things. The basal ganglia relays this information back to the cortex and other areas of the brain, forming a circuit. This circuit is important for learning how to execute precise motor behaviors like language or birdsong.

Although scientists once thought this circuit was only involved in song learning during development, they have since discovered another important role: altering the bird’s song performance to hone motor skills as an adult.

For example, when a male zebra finch sings alone, neurons in the circuit seem to fire randomly and the finch launches into a free-form improv session [audio: jazz music].

But if there happen to be a female zebra finch nearby, the neurons in the circuit fire in a regular, patterned way and the finch performs a well-rehearsed tune. [audio: guitar music]. From these experiments, scientists discovered this circuit helps us perfect our ability to sing, play guitar, ace our opponents and perform any number of activities.

By revealing how the songbird brain generates these different vocal behaviors, researchers are beginning to get a handle on motor learning throughout the lifespan and how social signals powerfully influence learning in all animals, especially highly social creatures like ourselves.[audio: background chirping and guitar music]

Also In Language

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org