This Is Where Your Brain Reads

- Published9 Sep 2025

- Author Kristel Tjandra

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Unlike speaking, modern human brains are not designed for reading. In fact, humans only began to read about 5,500 years ago. Yet reading is one of the most essential skills in our contemporary society.

“It takes years to actually learn this whole process,” said Sabrina Turker, a cognitive neuroscientist and linguist at Vienna University in Austria. We put together letters into syllables, syllables into words, and words into sentences. Identifying specific brain parts involved in each step can help scientists better understand the way we develop reading skills.

In a June 2025 study published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Turker and her colleagues plotted data from more than 3,000 individuals aged 18 to 45 who participated in 163 independent studies conducted by scientists over the past three decades. These studies used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of participants as they read. Participants carried out various reading tasks, such as reading a whole text, a sentence, a word, and even a pseudoword or made-up word, either aloud or silently. All of them read in alphabetic languages, including German, Italian, Spanish, and English. The result is the latest comprehensive brain map in reading research for alphabetic languages.

“When you merge [individual studies] together into a meta-analysis like this, you get a very good summary of what reading looks like in the brain,” said Mikael Roll, a neurolinguist at Lund University in Sweden.

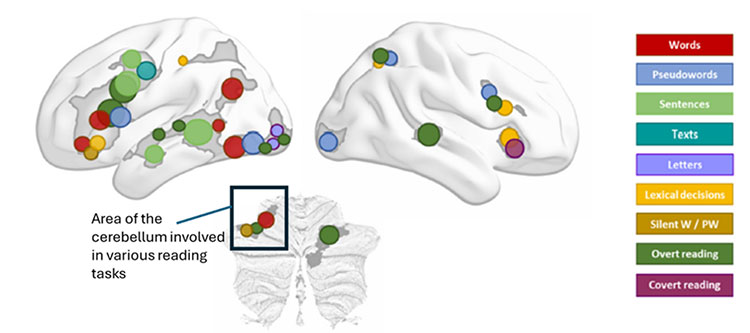

Turker and her colleagues found the cerebellum is active during various reading tasks.

“You can usually pinpoint one [major] function to one brain area, but the cerebellum just does a lot,” she said. By breaking down each reading task, Turker and her colleagues parsed specific areas within the cerebellum involved in different activities. For example, parts of the right cerebellum are more active when someone is reading aloud than when someone is reading silently. On the other side, areas in the left cerebellum are more active during silent word reading. Likewise, the left cerebellum is in play in semantics or deriving meaning from text, while the right is engaged in the reading process, such as generating speech.

The cerebellum’s major role in reading is in line with what some scientists, including Turker, have found in people with dyslexia or learning disorders, where the disruption in its activity leads to difficulty in automatizing reading skills. However, it’s not the whole story. The process of reading requires multiple parts of the brain.

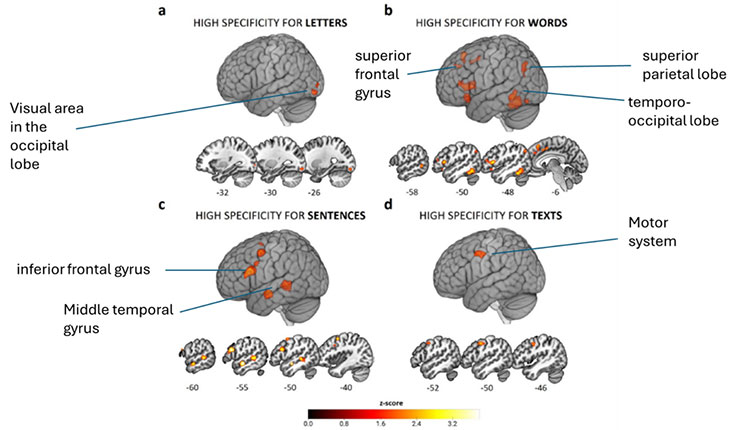

Some regions are specifically activated for each reading task. For example, letter reading mainly activates early visual areas of the brain. As we progress from letter to word, more brain areas come on board, including the visual word form area — located between the occipital and temporal lobes — the frontal lobe, and the superior parietal lobe.

“The visual word form area develops when kids learn to read,” Turker said. “This is the area that we know is [the] important [starting point] for sight reading or for retrieving all the knowledge you need to say a word, like how it sounds, what it means, how you pronounce it.”

The paracingulate and anterior cingulate regions in the frontal lobe have been shown to be active in managing attention and cognitive load. These areas are the most active when determining whether a word is a word, which reflects the decision-making that takes place when reading, Turker added.

As we read sentences, brain areas akin to meaning, grammar, and language begin to light up. These areas are clustered around the inferior frontal gyrus and the middle temporal gyrus. At the back of our brains are the lower-level sensory processing areas, such as those that deal with visual cues. As we move toward the frontal lobe, we encounter regions responsible for more complex processing, including semantics.

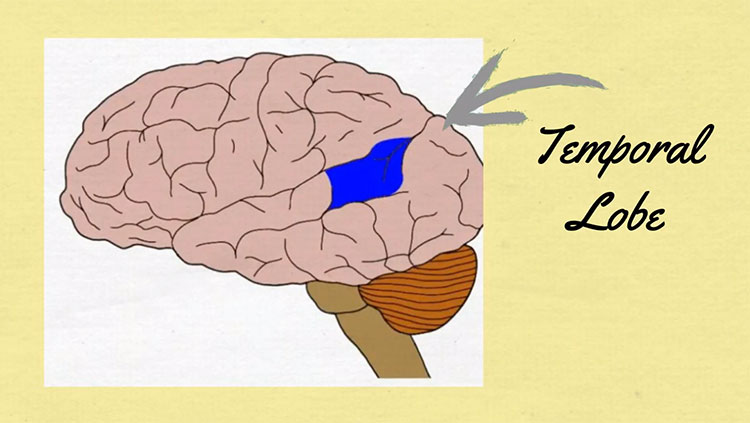

What’s distinct in sentence and text reading from other tasks is that the brain’s language network combines the meanings of each word into more intricate interpretation. With practice, reading can become effortless, but to some, this process may continue to be difficult throughout their lives. Through his research, Roll found that people who are good at reading tend to have different brain structures from those who struggle. For example, individuals who are better at recognizing and pronouncing words often have a larger left anterior temporal lobe.

Ultimately, this kind of map could help scientists begin to understand how different parts of the brain work together as we develop reading skills, Roll said.

“Neural activation is only one part,” Turker said. She plans to extend the study to look at reading development at various stages of life, from childhood all the way to 80 years old.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Gennari, S. P., Millman, R. E., Hymers, M., & Mattys, S. L. (2018). Anterior paracingulate and cingulate cortex mediates the effects of cognitive load on speech sound discrimination. NeuroImage, 178, 735–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.035

Roll, M. (2024). Heschl’s gyrus and the temporal pole: The cortical lateralization of language. NeuroImage, 303, 120930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2024.120930

Turker, S., Fumagalli, B., Kuhnke, P., & Hartwigsen, G. (2025). The ‘reading’ brain: Meta-analytic insight into functional activation during reading in adults. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 106166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106166

Turker, S., Kuhnke, P., Jiang, Z., & Hartwigsen, G. (2023). Disrupted network interactions serve as a neural marker of dyslexia. Communications Biology, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05499-2

What to Read Next

Also In Language

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org