Taking On Traumatic Brain Injury From All Angles

- Published8 Jun 2016

- Reviewed8 Jun 2016

- Author Teal Burrell

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

The story of an ex-football player suffering degenerative brain disease after a career filled with concussions dominates the news. So much so that parents have begun pulling their children from the sport. Yet, brain injuries also arise from concussive events like car accidents and battlefield explosions. Recent research show the manifestations of a brain injury depend on age, gender, and how the injury was sustained. Successful treatments may require taking these nuances into account.

Gender Differences

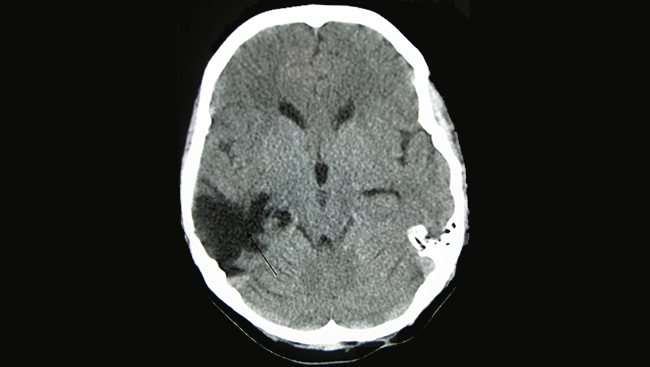

In 2010, 2.5 million Americans suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI), a head injury where the force of an impact causes the brain to slam into the skull, bruising tissue and tearing neurons. Afterward, inflammation in the injured area can disrupt signaling between cells. Injuries can range from a brief moment of confusion or loss of consciousness, such as a concussion, to long-term unconsciousness and amnesia. Common symptoms include impaired memory, dizziness, headache, and changes in mood and can last from weeks to years.

TBI research is often focused on men, as they are hospitalized for brain injuries more often than women and are three times more likely to die from TBI. However, many women are also injured every year — of the 2.5 million Americans who experienced a TBI in 2010, 1.1 million were women. When examining sports, like soccer and basketball, women actually experience more concussions than men.

Many studies report that women may also have worse outcomes after injury. One study found that three months after a mild TBI, women exhibited more symptoms than men. The difference was more pronounced for premenopausal women, suggesting hormones might play a role in recovery. But the effect of gender remains controversial, as a few studies have found the opposite. The disparity may be due, in part, to men and women experiencing different symptoms. Clinical reports suggest men may be more vulnerable to depression after TBI, while women may experience increased pain.

To examine this, researchers at Drexel University tested mice for both depression and sensitivity to pain after a mild TBI. Mice don’t like to swim and, when placed in a tank of water, most will paddle around and scratch at the walls to find a way out. After a while, mice will give up their search and float in the water instead. The researchers found injured male mice gave up swimming much sooner than both injured females and mice that hadn’t sustained a TBI, indicating depressive-like behavior.

On the other hand, when lightly touched near their eyes, injured female mice turned away or brushed the area much faster than injured males or uninjured mice, a sign of increased pain sensitivity. The male and female mice also differed in terms of brain chemistry, with males showing decreased signaling between nerve cells that use the neurotransmitter dopamine to communicate.

While it’s not clear why TBI affects men and women differently, study author Ramesh Raghupathi hopes his work will lead to the development of gender-specific therapies for TBI, either by treating the different symptoms seen in men and women or by targeting the underlying causes of the differences.

Age Effects

People may also respond differently to TBI depending on their age. For instance, one study compared recovery after injury in teenagers, people in their 30s, and adults over age 40. Over five years, the teenagers showed the most improvement in symptoms, while the older adults were more likely to have slipped further into disability.

The resiliency of younger brains has often been attributed to the fact that they are still developing. In its early stages, the brain is more malleable and able to rewire and reorganize as needed. “We’ve always assumed that’s a positive thing, that the net result is that we rewire for good,” says Trent Anderson of the University of Arizona. “But it may be that we’re actually rewiring for bad.” Other studies have shown, for instance, that children are actually slower to recover in the immediate months following injury, which may lead to trouble during the school years.

To find out what happens in the young brain after TBI, Anderson studied brain cell signaling in young mice. Some neurons turn other neurons on (exciting them), while some turn other neurons off (inhibiting them). A healthy brain has a careful balance of these “on” and “off” signals; too much excitation or inhibition can cause seizures or problems with memory or movement. Studies have shown that after a severe brain injury, this balance is upended in adults: Many types of inhibitory neurons are disrupted, resulting in too much excitatory signaling.

When Anderson looked at young mice with severe TBI, however, he found only one particular type of inhibitory neuron was altered. Scientists believe these neurons help synchronize and regulate brain activity. If TBI in children selectively disrupts the activity of these cells, it could explain why many children go on to develop post-traumatic epilepsy.

The findings from this and other studies highlight that there is “a real need to understand pediatric traumatic brain injury, independent of what might be going on in adults,” Anderson says.

Soldiers’ Battles

Different types of head injuries can also produce unique symptoms and consequences. One major current concern is injuries sustained by soldiers in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. TBIs on the battlefield are most often blast injuries from improvised explosive devices, which produce three separate attacks on the brain: shock waves and extreme pressure from the explosion, injury from flying objects, and impact of hitting the ground. Other TBIs, such as those from sports collisions or car accidents, don’t involve the pressure wave, the unique — and most damaging — element of blast injuries. Researchers are working to parse out precisely how the pressure wave damages the brain, beyond the impact with an object or the ground.

Soldiers are also at high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a debilitating condition in which fear and anxiety linger long after a traumatizing event. One recent study showed that TBI and PTSD might be related. When given a small foot shock, mice exposed to an injury similar to a blast injury froze more than uninjured mice, suggesting they had increased fear, a hallmark of PTSD.

“Mild traumatic brain injury can result in an emotional disturbance that is similar to post-traumatic stress disorder,” says Carmen Lin of Northwestern University who led the study. In addition, the injured mice had memory problems, a common symptom of TBI. When put back in the spot where they were shocked, the uninjured mice froze more often than the injured mice, indicating they remembered the earlier shock while the injured mice did not.

Lin hopes the results will increase awareness of the link between TBI and PTSD and improve diagnoses and therapeutic options for both disorders.

Just as no two brains are identical, no two brain injuries are identical. As researchers learn more about the various ways TBI manifests itself, more individualized treatments can be created.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Andruszkow H, Deniz E, Urner J, et al. Physical and psychological long-term outcome after brain injury in children and adult patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12 (2014).

Asemota AO, George BP, Bowman SM, et al. Causes and trends in traumatic brain injury for United States adolescents. J Neurotrauma, 15: 67-75 (2013).

Bazarian JJ, Blyth B, Mookerjee S, et al. Sex differences in outcome after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma, 27: 527-539 (2010).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury Prevention and Control: Traumatic Brain Injury and Concussion.

Colantonio A, Harris JE, Ratcliff G, et al. Gender differences in self-reported long-term outcomes following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurology, 10 (2010).

Dick RW. Is there a gender difference in concussion incidence and outcomes? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 34: 46-50 (2009).

Marquez de la Planta C, Hart T, Hammond FM, et al. Impact of age on long-term recovery from traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 89: 896-903 (2008).

Lin C. Mice with mild traumatic brain injury from blast show increased fear behaviors. Press conference at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (2015).

Raghupathi R. Male and female mice display different symptoms months after mild traumatic brain injury. Press conference at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (2015).

Also In Injury

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org