Talking Heads: Rebuilding Language After Stroke

- Published20 Nov 2009

- Reviewed20 Nov 2009

- Source Wellcome Trust

Stroke can affect any part of the brain, resulting in the death of tissue vital for the brain’s normal functions, including language. In this film we meet Tess and Michael, who have each had a stroke affecting language in very different ways.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

Wellcome Trust

Transcript

Tess Lancashire, Facilitator for the charity Different Strokes, and Michael Green talk about their experiences of stroke affecting their language, and Dr Alex Leff and Professor Cathy Price of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging’s Language Group talk about their work using fMRI to study language function. Also featuring Louise Ambridge, Speech Therapist and Research Assistant, and Michael’s wife Jean Green.

MG: Dowfing. Er, jerryvesh, jerrygesh, no.

LA: The right number of sounds.

The right number of sounds.MG: Closely, chaufery. How’s that?

Closely, chaufery. How’s that?LA: Cigarette.

Cigarette.MG: Cigarette?

Cigarette?LA: Yes.

Yes.MG: Baff. F, A, S.

Baff. F, A, S.AL: Language is incredibly significant, it’s one of the things that makes us human really, and if

Language is incredibly significant, it’s one of the things that makes us human really, and ifyou talk to patients who are at risk of stroke they’ll often be most worried about losing their

language; that’s the thing that people are worried about stroke, worried about the most.

TL: I could feel it in my head that I’m still me, this is me, but I just couldn’t do anything – at all. I

I could feel it in my head that I’m still me, this is me, but I just couldn’t do anything – at all. Icouldn’t speak, I couldn’t read, I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t get people to understand me and I

couldn’t understand them, and it was absolutely horrendous.

JG: Can you remember where you were when you had your stroke?

Can you remember where you were when you had your stroke?MG: Talking on the television in America. I tell this to somebody and they said “er, what are you

Talking on the television in America. I tell this to somebody and they said “er, what are youtalking about?” And I said “what?” – and I’d gone, I’d gone.

AL: About 80 per cent of strokes are caused by the blood supply becoming blocked and then

About 80 per cent of strokes are caused by the blood supply becoming blocked and thenabout 20 per cent of strokes are caused by the opposite, if you like, when a blood vessel breaks,

a haemorrhage, so where blood spurts into the brain and causes direct damage to the brain.

CP: When they come in for testing here we use a battery of tests that attempts to assess their

When they come in for testing here we use a battery of tests that attempts to assess theirabilities from multiple different angles and in a very controlled way.

LA: I’m going to give you one minute and ask you in that time to name as many animals as you

I’m going to give you one minute and ask you in that time to name as many animals as youcan think of.

TL: Horse, cat, cow, dog, mouse, sheep… [pause]

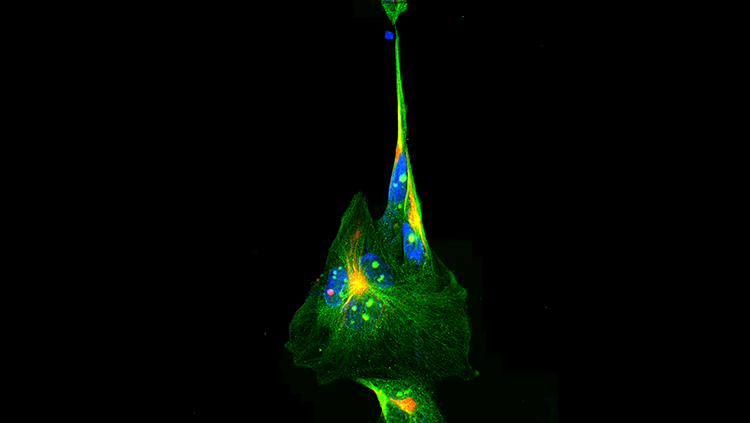

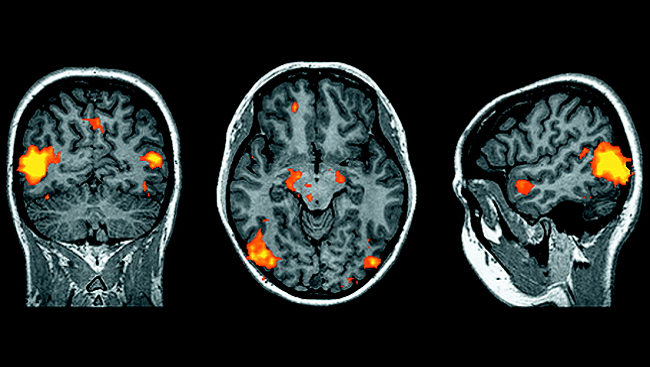

Horse, cat, cow, dog, mouse, sheep… [pause]CP: OK, what imaging does is two things: one, it tells us very precisely where the stroke is and

OK, what imaging does is two things: one, it tells us very precisely where the stroke is andwhich areas have been damaged, but that means nothing unless we know what those areas are

normally involved in. So to understand what they’re normally involved in we use functional

imaging, and functional imaging tells us which bits of the brain are activated when you do a

particular task.

Much of what we’ve seen is not that the patient who’s had a stroke uses a completely new set of

regions to support their recovery, and it’s not that the right hemisphere suddenly takes over from

the left hemisphere, it’s that there are brain areas left that are able to carry out the same task in a

slightly different way but to get to the same end point.

What the patient wants to know is: am I going to recover, when am I going to recover, how well

am I going to recover? And that information we can already give them if we can tell them about

other patients, but the only way we can tell them about other patients is to try and test as many

patients as we can over time, so at many points after they’ve had a stroke, so that we can use the

information from our volunteers to help other patients, and that’s why we’re always constantly

looking for patients who’ve had strokes and asking them can they come in and can they help us

to help other new patients to predict how they might recover.

MG: In your head [points at head] it’s fine, in the head [points at mouth] – nothing.

In your head [points at head] it’s fine, in the head [points at mouth] – nothing.JG: So here it’s great but when it gets down to here it’s terrible.

So here it’s great but when it gets down to here it’s terrible.MG: There’s a [unclear] here somewhere, there’s some [unclear].

There’s a [unclear] here somewhere, there’s some [unclear].JG: We need a little tube to join up. [Laughs]

We need a little tube to join up. [Laughs][End of transcript]

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org