Teens, Neuroscience, and Society

- Published1 Nov 2011

- Reviewed1 Nov 2011

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Adolescence is a time of significant changes for both the body and the brain. Conflicts with authority figures, mood swings, and other behavioral problems are often normal during the teen years, and scientists are starting to figure out why. Imaging research shows the brain continues to develop into a person’s 20s and 30s. And while current research suggests the teenage brain is positioned for maximum learning and growth, it also may make adolescents particularly vulnerable to impulsive actions, irritability, and performance problems. Teen brain development comes into play in many facets of their young lives.

The Adolescent Brain: Still Developing

During childhood, the brain busily forms new cells and fibers between these cells, which is thought to contribute to the impressive rates that children learn new knowledge. The rate of formation of synapses, or connections, between brain cells peaks during childhood but is still higher in teens than adults. Also, the brain begins pruning excess or unused cells and their connections around puberty — a period that coincides with increased reasoning capabilities.

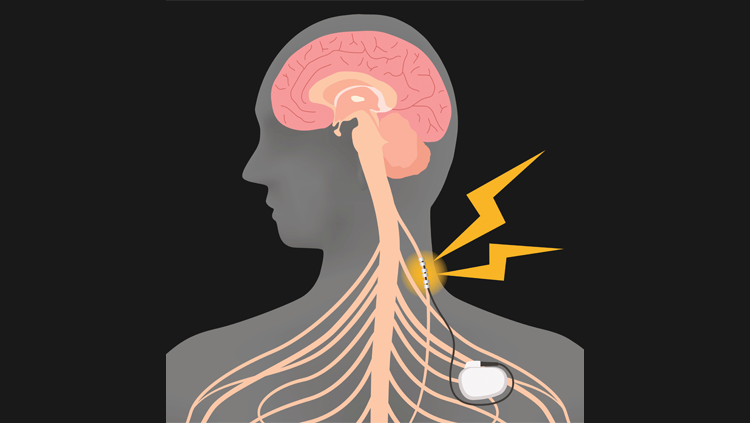

The branches of brain cells also undergo major changes as they become encased by a fatty material called myelin, facilitating fast-paced movement of electrical signals between brain regions. While this process, known as myelination, begins in infancy, it is not complete until adulthood, suggesting that the teen brain processes information at a slower pace than the adult.

This remodeling of the brain takes place at different stages, with the back of the brain maturing before the front. The frontal lobe — the brain’s self-control and judgment center — is the last to complete development, concluding sometime in the mid- to late-20s. This may set the stage for common teenage behaviors like risk-taking and novelty-seeking.

Sleep, Learning, and Memory

As all of these developmental changes are occurring, many behavioral shifts also are at work. Sleep patterns, for instance, are shifting. Sleep’s role in learning and memory is a major topic of active research, and these links may influence the developing teen.

Even before puberty, sleep and wake periods begin to shift. One study showed that unlike adults and younger children, 10-12 year-olds experience periods of wakefulness at night, after they have already been awake for a full day. During the teen years, levels of the hormone melatonin, which promotes sleep, rise later in the evening and fall later in the morning than those of children and adults.

These findings may explain why many teens stay up late and have difficulty rising. Most teens report getting significantly less sleep than the nine hours per night encouraged for this age group. Many education advocates worry that sleep deficits and daytime drowsiness pose problems for learning and attention in the classroom. Some U.S. school systems have used this research to support later start times for high schools, which traditionally begin before 7:30 in the morning

Teens and the Law

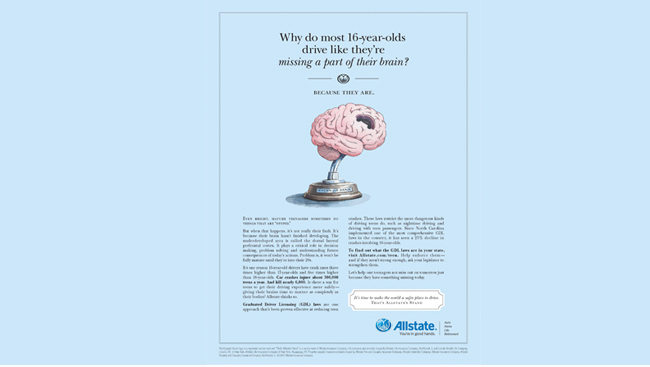

In the United States, some laws and regulations acknowledge that teenagers are still developing maturity and responsibility. For example, many states have graduated driver licensing systems, allowing teens a learning period to develop the decision-making skills necessary for driving. Many of these programs require supervised driving experiences and limit the number and ages of passengers.

These programs may reflect the fact that teens are more prone to distraction. Driving simulation studies suggest that unlike older drivers, who were not affected by additional passengers, younger drivers make riskier decisions in the presence of their peers. This may explain why car accident rates for 16 and 17 year-old drivers increase with each additional passenger.

Other research shows teen brains work harder to assess whether a scenario is dangerous, showing increased activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This greater effort translated into longer reaction times, which could lead to trouble behind the wheel. While graduated driving licensing laws treat teens differently than adults, some laws do not. Although teen offenders are generally processed through the juvenile court system, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention indicates that 22 U.S. states fail to specify a minimum age for transferring adolescents to adult criminal court. Ongoing research may help inform the legal system to determine the degree of culpability of teens, who may lack maturity and impulse control.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN