Animal Research Success: Polio

- Published9 Mar 2012

- Reviewed9 Mar 2012

- Author Emily K. Dilger, PhD

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

During the first half of the 20th century, no disease was feared more than polio, a virus that can invade the nervous system and infect and destroy nerve cells controlling muscles in the spinal cord and brain. Once infected, an individual may experience paralysis, muscle breakdown of the legs and arms, and trouble breathing. Today, however, polio is all but eliminated worldwide because of a highly effective vaccine, originally tested in monkeys.

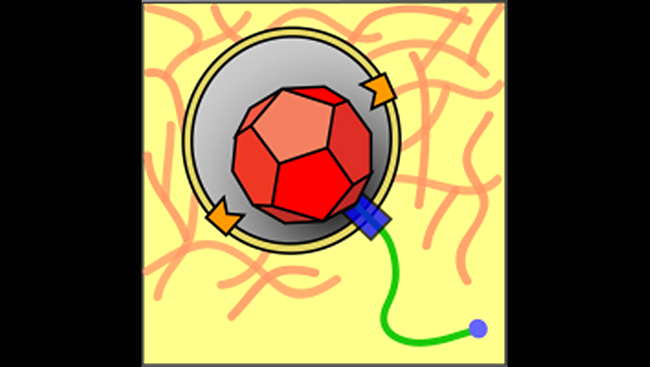

The polio virus looks a bit like a cut jewel with many sides, illustrated by the red polyhedral shape shown here. When the virus enters a host cell, it releases its genetic information, shown in green. The host cell, believing the genetic information is its own, produces the virus’ proteins, causing disease.

The first significant breakthrough came in the early 1900s, when Austrian scientists Karl Landsteiner, MD, and Erwin Popper, MD, showed that polio was an infectious disease caused by a virus. They discovered that monkeys injected with extracts of the disease from the spinal cord of a boy who had died from it contracted polio. This meant that scientists all over the world could take extracts of the disease and infect other monkeys, allowing different groups of scientists to study the disease simultaneously.

The work of these other scientists led to two more important discoveries. First, they learned that there are three strains of the virus, indicating that a successful vaccine would have to protect people against all three. Second, they discovered that the virus enters the body through the mouth and moves through the intestines before it infects nerve cells. With these findings in hand, scientists realized that a vaccine could provide the body with the means to fight the virus before it reached the brain.

Researchers continued their work. Eventually, a strain of polio was successfully transmitted to the rat and the mouse, enabling scientists to study polio in smaller animals. In 1949, Thomas Weller, MD, John Enders, PhD, and Frederick Robbins, MD, discovered a way to grow the polio virus safely in tissue cultures, allowing other scientists to produce their own supplies of the virus – a step essential for the development of a vaccine. For this work, they won the 1954 Nobel Prize.

The first vaccine, the Salk vaccine, was made from an inactivated strain of polio. The only way people could receive this vaccine was via an injection given by a trained health worker. Later, the Sabin vaccine, an oral form made from a live, weakened virus, was developed. This vaccine does not require trained health workers or sterile injection equipment, making it much more versatile. These vaccines put polio on target to become the second human disease to be eradicated worldwide (smallpox was the first). However, after recent outbreaks of polio in countries where it had been absent for many years, scientists have realized that polio is still a threat, pointing to the importance of continued research.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org