Animal Research Success: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Published9 Mar 2012

- Reviewed9 Mar 2012

- Author Emily K. Dilger, PhD

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

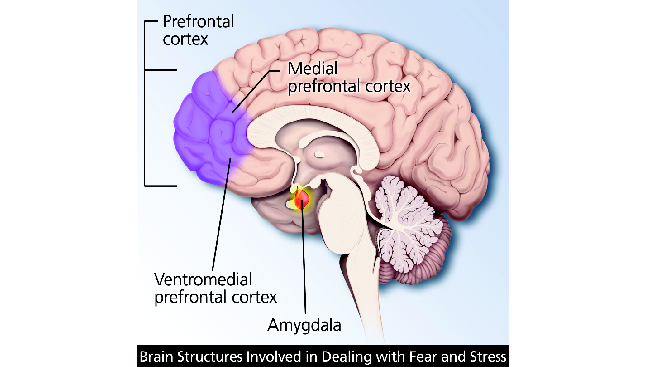

Animal research has shown that long-term activation of the stress system can lead to serious health risks, and has given us a better understanding of how stress damages the brain. When a person encounters a stressful situation, the adrenal gland releases norepinephrine and cortisol, hormones that circulate through the bloodstream to alert the rest of the body to react to the danger. These elevated levels enhance the function of the amygdala, a region of the brain that plays a role in understanding and remembering emotional events, especially ones that cause fear.

Patients with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) have heightened levels of norepinephrine, a chemical involved in arousal and stress. High levels of this chemical strengthen the emotional reactions of the amygdala, a brain region involved in the fear response, while weakening the rational functions of the prefrontal cortex, which normally allows us to suppress troubling memories and thoughts. Research shows that a drug called D-cycloserine, when used in combination with behavioral therapy, appears to help patients find some relief from these symptoms.

In normal situations, this is a good thing; it can push us to do our best on the report due next week. However, an especially traumatic event can cause post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which occurs when the stress system fails to recover from the event. This results in recurring flashbacks that can disrupt everyday life. Animal research has led to a deeper understanding of PTSD, enabling scientists to develop therapeutics that lessen the number or intensity of a person’s flashbacks.

Research in rats and monkeys has given us insight into one possible explanation for PTSD. The prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain involved in complex forethought, may also be involved in blocking repeated fear responses to the same stimulus. However, high levels of norepinephrine can impair the prefrontal cortex so that fear responses are not blocked. Instead, they are constantly brought up. Animal studies have shown that by reducing high norepinephrine levels, the appropriate activity in the prefrontal cortex can be restored and inappropriate overactivity of the amygdala can be dampened. Today, some norepinephrine-based drugs are used to help treat patients with PTSD.

Long-term or high levels of cortisol can also have damaging effects, causing toxicity and shrinkage of brain regions such as the hippocampus, a structure involved in memory formation. Research in rats has shown that cortisol can induce neuron damage and decrease neurogenesis, the birth of neurons. However, these effects may also be treatable, and animal research has turned scientists toward medications that protect the brain of people with PTSD from cortisol damage to the hippocampus.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org