Animal Research Success: Stroke

- Published9 Mar 2012

- Reviewed9 Mar 2012

- Author Emily K. Dilger, PhD

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

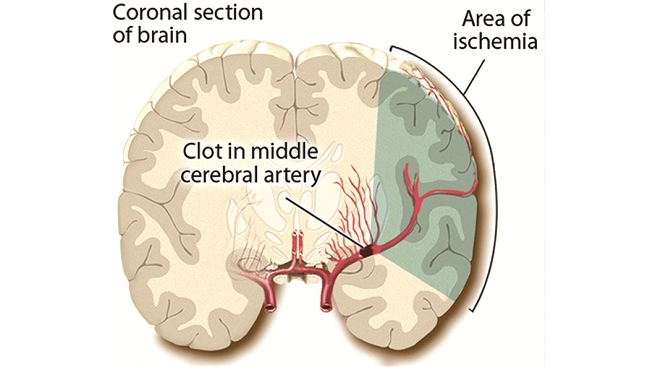

As with any other part of the body, the brain needs a constant supply of oxygen, which is carried to the brain in blood. A stroke occurs when one of the blood vessels that supplies the brain with blood is blocked by a blood clot or the vessel bursts. As a result of the interrupted blood flow and oxygen supply, neurons can be damaged or die. Unfortunately, since most neurons do not have the ability to divide or replace themselves, cells and the functions that they perform can be permanently lost during a stroke.

A stroke occurs when a blood vessel bringing oxygen and nutrients to the brain bursts or is clogged by a blood clot. Depending on its location, a stroke can cause permanent problems, such as paralysis on one side of the body or loss of speech.

The consequences of stroke can range from paralysis to loss of speech, as well as many other disabilities, and even death. Today, there is only one established clinical treatment for stroke, which was developed following experiments observing stroke in rabbits. Researchers gave the rabbits a molecule found in the body called tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Under normal circumstances, after an external injury, the body forms a blood clot to protect the injury during the healing process. The function of tPA is to break down the clot after it is no longer needed. Applying this knowledge to strokes, researchers realized that they could give tPA immediately after a stroke. When this was tried with rabbits, scientists found that tPA was able to break down the blood clot that was causing damage. In humans, when the clots that were blocking blood flow to the brain were relieved soon after they first occurred, patients did not suffer permanent damage, pointing to the benefit of tPA as a treatment for stroke.

Animals are also helping scientists study rehabilitation of stroke patients. Specifically, scientists are investigating whether other neurons can be trained to take over functions of the cells that died. Researchers studying monkeys found that by restricting the monkey’s use of its stronger arm, the animal will use its weaker arm. Increased use pushes surviving nerve cells to take on new functions. Follow-up studies in human stroke patients have confirmed the value of this approach.

Through work with animals, scientists have discovered the value of developing drugs that reduce the number of tissue-damaging chemicals released when neurons suffer oxygen loss. Such therapies are being tested in ongoing clinical trials in people who have suffered stroke. To date, however, none have been shown to be effective.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org