Chemo Brain: The Fallout from Cancer Treatment

- Published26 Jun 2012

- Reviewed26 Jun 2012

- Author Marilyn Fenichel

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

For cancer patients, it’s a long haul from the time of diagnosis to the end of treatment. After numerous rounds of chemotherapy, patients feel relieved they survived and look forward to moving on. Unfortunately, however, another obstacle may stand in their way — a condition called chemo brain.

Chemo brain is a catch-all term for cognitive deficits following chemotherapy, a common cancer treatment where the body is treated with chemicals meant to kill fast-growing cells. People report short-term memory loss, difficulty retrieving information, problems switching from one task to another, and problems with attention.

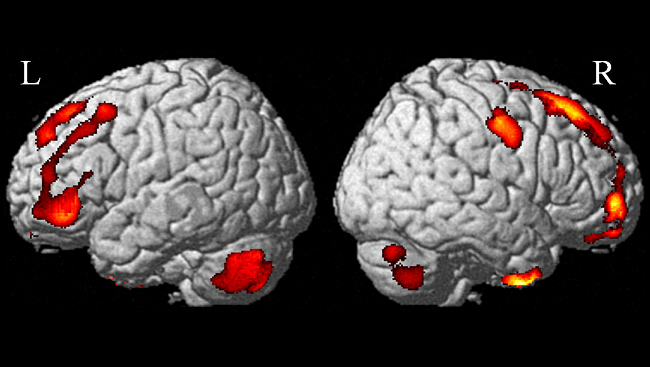

Scientists believe that chemotherapy-induced memory loss may be attributable to damage to the hippocampus, a brain structure vital to memory, while injury to the frontal lobe can lead to problems with cognitive function and control. More than 70 percent of patients find these difficulties subside several months after treatment ends, but at least one-fourth of that group continues to have these problems five and even ten years later. Women who have been treated with chemotherapy for breast cancer are particularly susceptible.

Vulnerable brain cells

Researchers have investigated these issues for more than a decade. In 2006, research from a team led by Mark Noble, professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center, revealed the extent of the problem: common chemotherapy drugs used to treat breast, ovarian, and colon and rectal cancer, as well as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, were more toxic to multiple kinds of brain cells than the cancer cells themselves.

A later study by Noble’s team done in mice showed that another commonly used chemotherapeutic drug caused damage to oligodendrocytes, the cells that cover axons with myelin. Myelin helps expedite messaging among nerve cells, or neurons. When oligodendrocytes are damaged, myelin breaks down, disrupting communication among the nerve cells vital to brain functioning.

Crossing the barrier between brain and body

Another team from the University of Rochester Medical Center hypothesized the drugs that cause chemo brain are those best able to cross the blood-brain barrier, a network of blood vessels that prevents more than 95 percent of all chemicals from entering the brain from the bloodstream. They tested this hypothesis by giving one group of mice a standard dose of cyclophosphamide and fluorouracil, which do cross into the brain, and a second group paclitaxel and doxorubicin, which do not. Surprisingly, all four drugs resulted in the breakdown of brain cells. The largest reduction in brain cells came from paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide (36 and 31 percent, respectively). Fluorouracil and doxorubicin produced lower reductions (15 and 22 percent, respectively).

Robert Gross, a professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center and the study’s principal investigator, offered one possible explanation for these findings. “It could be that all of the chemo drugs cross into the brain after all, or that they act via peripheral mechanisms, such as inflammation, that could open up the blood-brain barrier.”

Understanding the full impact

What can be done to offset these problems? Promising animal research at the University of Rochester suggests that the growth factor IGF-1 may help. When administered to mice under certain conditions — before and after receiving a single or multiple-dose regimen of cyclophosphamide — IGF-1 seemed to increase the number of new brain cells, although it did appear to be more effective in the high-dose model.

“We’re still trying to understand the causes of chemo brain,” Gross said. “We plan to conduct additional studies to further test the impact of IGF-1 and other related interventions on the molecular and behavioral consequences of chemotherapy.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org