Narcolepsy

- Published29 Feb 2012

- Reviewed29 Feb 2012

- Author Susan Perry

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Narcolepsy is a neurological disorder that causes people to feel sleepy and tired all the time, and to have a lot of abnormal dreams. Its symptoms can interfere with a person’s ability to lead a normal, active life. Scientists have made great strides in identifying some of narcolepsy’s underlying genetic and neurobiological causes — discoveries that are helping to understand the biological mechanisms of sleep disorders and may point to new treatments.

Imagine suddenly falling asleep in the middle of eating a meal or talking with a friend. Then imagine waking up and being unable to move a single muscle. Or speak.

These are classic symptoms of narcolepsy, a chronic sleep disorder that affects an estimated 150,000 Americans. Besides excessive daytime sleepiness (which can lead to sudden sleeping attacks) and bouts of sleep paralysis, some people with narcolepsy also have sleep-related hallucinations, vivid dreams, and cataplexy, a sudden loss of muscle tone that can cause all or part of the body to temporarily collapse. Cataplexy is often triggered by a strong emotion, like laughter.

There is currently no cure for narcolepsy, but its symptoms can be managed, usually with a combination of drugs that promote daytime alertness and lifestyle changes that encourage frequent naps. Even with treatment, narcolepsy can be debilitating, interfering with personal relationships and daily activities.

For centuries, narcolepsy puzzled doctors. Some even thought it was a psychological illness. But in recent years, scientists have discovered narcolepsy is a distinct neurological disorder linked to certain genetic risk factors, a specific protein in the brain, and an overactive immune system. Ongoing studies in this field are leading to:

- A greater understanding of narcolepsy and other sleep-related disorders.

- More effective treatments for people with such disorders.

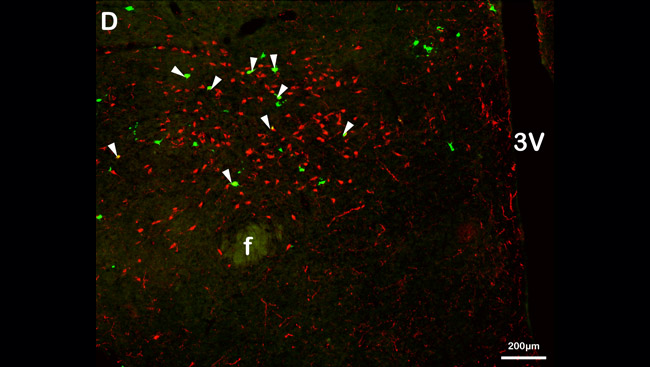

The big breakthrough in narcolepsy research came in 1998 when two teams of scientists working in separate laboratories discovered a previously unknown protein in a few cells of the hypothalamus, a brain region that controls many metabolic functions, including body temperature, hunger, thirst — and sleep. This protein, orexin (also called hypocretin), promotes arousal and wakefulness and inhibits REM sleep, the intervals during sleep when dreams occur and when muscles become inactive.

Researchers studying dogs with narcolepsy found a link between the disease and the new protein. They found the dogs had a mutation in a gene important for orexin/hypocretin function. Furthermore, when scientists manipulated this gene in mice, those animals also developed symptoms of narcolepsy.

Other studies quickly linked orexin/hypocretin with narcolepsy in people. Tests revealed many people with narcolepsy had lower-than-normal levels of orexin/hypocretin in their cerebrospinal fluid (fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord). And autopsy studies demonstrated people with narcolepsy had up to 95 percent fewer orexin/hypocretin-containing cells in their brains. This finding, and the observation that narcolepsy typically begins during adolescence or early adulthood, suggested the orexin/hypocretin cells were destroyed sometime after birth.

Scientists knew, however, that unlike narcolepsy in dogs, human narcolepsy could not be traced to a single defective gene. Only about 10 percent of people with narcolepsy have a close relative, such as a parent or sibling, with the disorder. And among identical twins — who share all the same genes — one twin may have narcolepsy while the other does not.

In humans, therefore, narcolepsy most likely involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Certain individuals may inherit a genetic susceptibility to narcolepsy, but not all will go on to develop the disorder.

The search for other genetic factors involved in human narcolepsy has led scientists to a group of genes known as the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex, which perform a central role in the immune system. They help the body differentiate between its own cells and potentially dangerous “foreign” cells, such as bacteria and viruses. Researchers found many people with narcolepsy that includes cataplexy have an HLA or HLA-related gene defect.

More recently, scientists discovered another gene variant in the immune system associated with narcolepsy that includes cataplexy. This gene variant is associated with specialized immune cells known as T cells, which attack and destroy any foreign cells identified by HLA molecules. Scientists now believe that the narcolepsy-related HLA and T-cell variants cause the immune system to somehow “gang up” to kill orexin/hypocretin cells in the hypothalamus. Why they do this — or what sparks the attack in the first place — remains a mystery. Many researchers suspect environmental factors, such as infections, may be involved.

As scientists continue to narrow their search for the specific causes of narcolepsy, they also are exploring new therapies, including testing the effect of orexin/hypocretin treatment. In addition, they are investigating possible ways of reversing the destruction of orexin/hypocretin cells, perhaps through cell transplantation.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org