Yawning

- Published20 Mar 2012

- Reviewed20 Mar 2012

- Source CIHR – Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction

Yawning is both familiar to everyone and totally mysterious, as scientists continue to puzzle over its possible functions.

Yawning is a behavior found in fish, reptiles and birds, as well as in humans. Described in ancient times by Hippocrates (who thought it served to evacuate fever), yawning did not become a subject of serious interest until the advances achieved in neuroscience in the 1980s.

Generally speaking, yawning consists of three phases: first, a long intake of air, then a climax and finally a rapid exhalation, which may or may not be accompanied by stretching. After yawning, you generally experience a sense of well being and relaxation and feel much more present in and aware of your body than before a yawn.

Contrary to what was believed for centuries, yawning does not serve to improve oxygenation in the brain. This myth was first laid to rest when it was discovered that the human fetus can yawn as early as the age of 12 weeks, even though it is surrounded by amniotic fluid in its mother’s belly and so is unlikely to get any more oxygen to its brain from this effort.

Second, if yawning really helped to raise the oxygen concentration in the blood, then inhaling pure oxygen would cause yawns to become less frequent, while raising the concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood would make them more frequent. But several studies have shown that neither of these things occurs. Also, yawning is no more common in people with acute or chronic respiratory problems than it is in the general population.

The role of yawning has yet to be fully determined. But because we yawn more often when we first awaken, when we are bored, and when we are trying not to fall asleep, its primary function would appear to be to help make us more alert. Yawning also seems to play a role in non-verbal communication, especially among primates.

Which leads us to something truly singular about yawning: its contagiousness. That is, when we see someone yawn, it makes us yawn. Sometimes simply thinking about a yawn can be enough to trigger one. Obviously, the term “contagiousness” should not be taken literally here because no germs are being transmitted. More precisely, yawning is a form of involuntary imitation. Some scientists believe that this characteristic of yawning may have developed as a mechanism for promoting social cohesion by enabling all the people present in a group to have the same level of alertness at the same time.

In the rest of the animal kingdom, yawning is observed among predator and prey species alike. Among predators, its purpose might be to encourage the group to take a restorative nap so that all of its members can be well rested for an attack on their prey later on. Among prey, by encouraging all members of the group to fall asleep at the same time, yawning might reduce the risk that any one individual might be sleeping alone and hence highly vulnerable to attack by a predator.

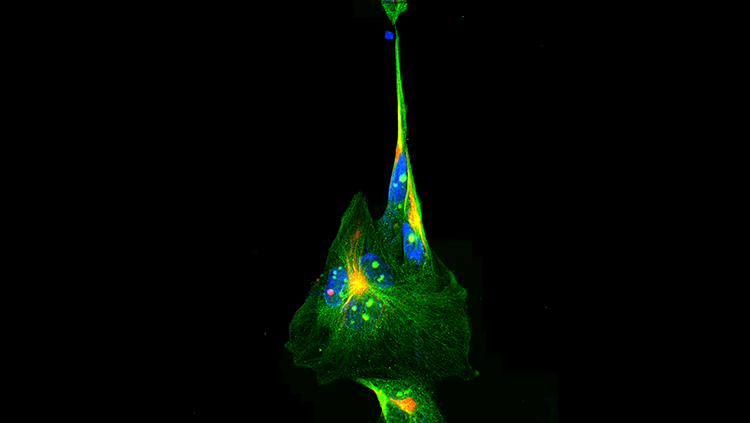

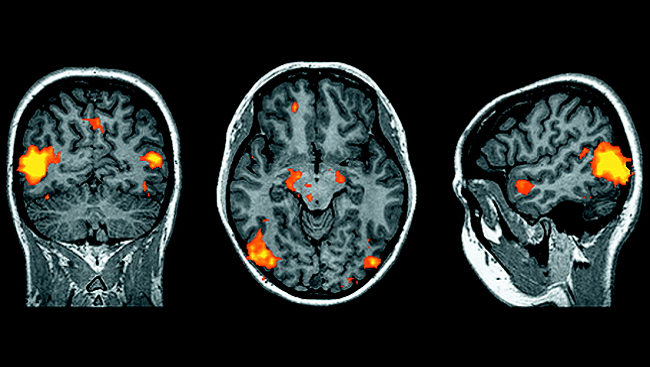

There is no nerve center strictly associated with the yawn reflex, but certain brain structures, such as the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the brainstem are essential for its expression. Some scientists have even hypothesized that the strong contractions of the jaw muscles during yawning may stimulate the reticular formation and thereby encourage wakefulness.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

CIHR – Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org