I was nervous, not knowing what to expect. I walked into the room, inhaled deeply and got a bit dizzy. The lighting was harsh and bright, but I was thankful because I wanted to see it all. I moved toward the table where I would be doing it. The table was stainless steel, sterile, and cold. And there at one end was the object of my affection: a human brain.

I was in graduate school and had joined the medical students in their second semester anatomy class, which was dedicated solely to studying and understanding arguably the most complex of all human organs, the brain. And I was lucky enough to join them.

The med students spent their first semester dissecting and understanding the human body up close and personal. I assume they examined the heart, prodded the liver, and cut open the spleen. They most likely dissected the spinal cord and peeled back layers of skin to understand how all the pieces worked together normally so that they would understand what was wrong when they saw the living tissue in their own practices. They did this all in the name of education.

Medical schools get their cadavers from people who donate their bodies to science. I will forever be grateful to John or Jane Doe (identities are kept secret) who made the decision to give of him- or herself one last time. My own brain could not wrap itself around the fact that I was studying the very thing that I was using to study. (That sentence gives me a headache now as I try to parse its meaning.) As I gently traced the contours of the brain and allowed my fingers to go in and out of the gyri and sulci (the bumps and grooves on the surface of the brain), I marveled at how this architecture allowed humans to have such great intellectual power. If we had a smooth brain, there would not be enough room in our heads for all the brain cells and connections that make us uniquely human.

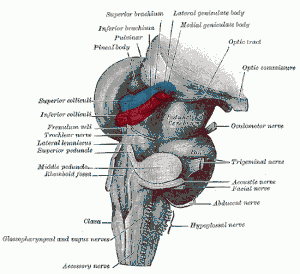

I remember cutting into the brain tissue for the first time. It had the consistency of tofu. As I peeled back the outside layers of neocortex and dug down into the subcortical layers, I saw the structure that I had been reading about and writing about and thinking about for many years. The superior colliculus. It’s “superior” because it is located above its “inferior” counterpart: the inferior colliculus. “Colliculus” is Latin for “mound” and is an apt name for these tiny structures that bump out just slightly from the surrounding tissue on the midbrain.

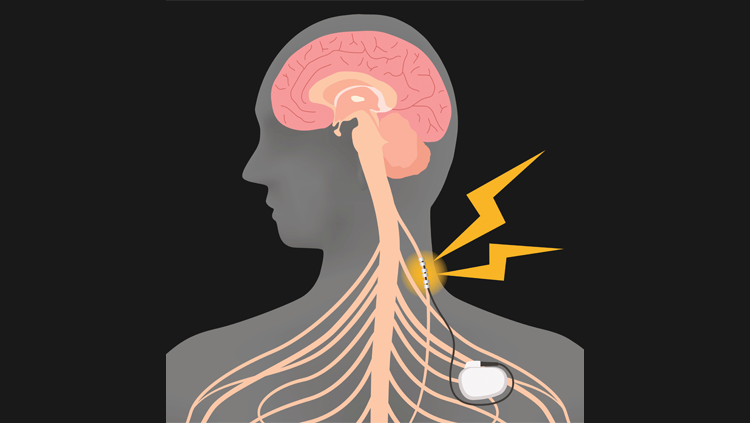

If I had to name a favorite brain part (an exercise I have my students do), the superior colliculus would be it. Hands (or neurons) down. The SC (as those of us in the know – including you now – abbreviate it) is a magnificent structure about the size of a pea. It has multiple maps of space and gets information from your eyes, ears, and skin. This is the sensory side of the SC. It also has a motor side. It is instrumental in moving your eyes. That’s right, as you whip your eyes around the world at a rate of about 3 times per second, your SC is working overtime to make sure that your eye movements are directed where they should. And, if you land short of your target, your SC gets them moving again.

Many brain parts are named after the things they look like and where they are located. Hence, the SC is named as such because it’s a little mound that is above another little mound. There is another brain part called the hippocampus, and I bet most of you have heard of it before. It is extremely important for learning and memory. It is named hippocampus because it looks like a seahorse and “hippocampus is derived from the Greek hippokampus (hippos, meaning “horse,” and kampos, meaning “sea monster”)”. Looking at the picture to the left, I see why it got that name. However, during a dissection, that is not the impression one usually gets.

I remember gently pulling back the outer layers of the temporal lobe when I noticed that some of the inner brain tissue did not seem to be connected. I carefully removed the outer layer and there was a very smooth structure staring at me. The anterior (front) portion looked like a cat’s paw (without the claws) and the arm seem to go back into the tissue somewhere toward the middle of the brain. I can still see the structure now in my mind's eye. I am still in awe that such a thing exists in my head (actually two such things – you have one in each hemisphere of your brain). The fact that I can remember this now is a testament to the work the hippocampus did all those years back. The hippocampus is involved in consolidating short-term memories into long-term memories.

So you see - I am truly grateful to the individual who donated his/her body to science and I like to think that I honor that person every day with the knowledge I gained from that semester’s hand-on training. Someday, I hope to return the favor.