Vision: Processing Information

- Published1 Apr 2012

- Reviewed29 Jul 2016

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

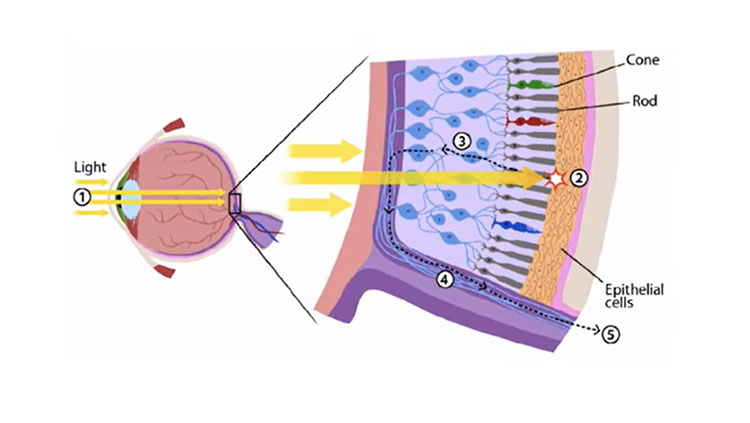

The moment light meets the retina, the process of sight begins. About 60 years ago, scientists discovered that each vision cell’s receptive field is activated when light hits a tiny region in the center of the field and inhibited when light hits the area surrounding the center. If light covers the entire receptive field, the cell responds weakly.

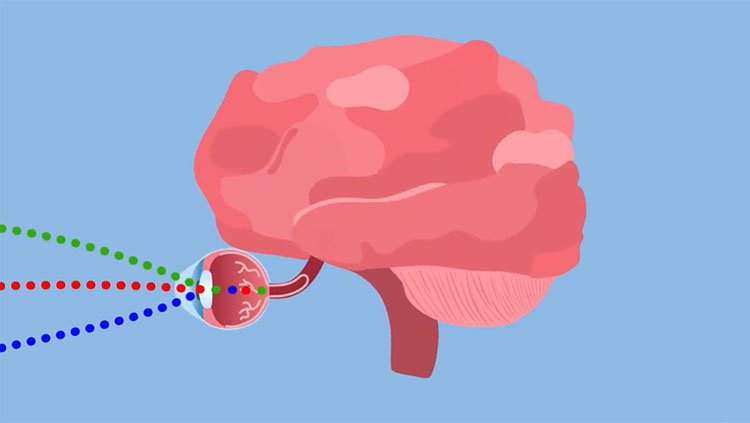

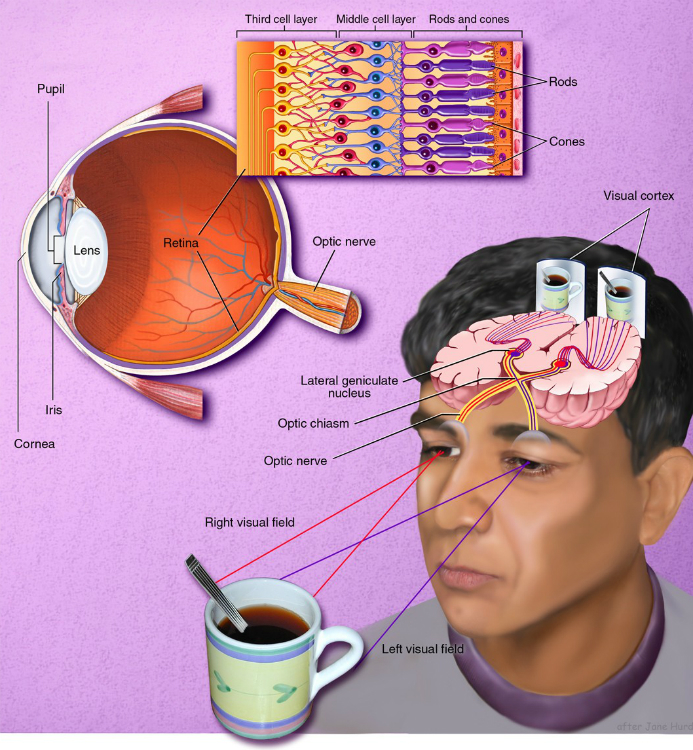

Vision begins with light passing through the cornea and the lens, which combine to produce a clear image of the visual world on a sheet of photoreceptors called the retina. As in a camera, the image on the retina is reversed: Objects above the center project to the lower part and vice versa. The information from the retina — in the form of electrical signals — is sent via the optic nerve to other parts of the brain, which ultimately process the image and allow us to see.

Thus, the visual process begins by comparing the amount of light striking any small region of the retina with the amount of surrounding light.

Visual information from the retina is relayed through the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus to the primary visual cortex — a thin sheet of tissue (less than one-tenth of an inch thick), a bit larger than a half-dollar, which is located in the occipital lobe in the back of the brain.

The primary visual cortex is densely packed with cells in many layers, just as the retina is. In its middle layer, which receives messages from the lateral geniculate nucleus, scientists have found responses similar to those seen in the retina and in lateral geniculate cells. Cells above and below this layer respond differently. They prefer stimuli in the shape of bars or edges and those at a particular angle (orientation). Further studies have shown that different cells prefer edges at different angles or edges moving in a particular direction.

Although the visual processing mechanisms are not yet completely understood, recent findings from anatomical and physiological studies in monkeys suggest that visual signals are fed into at least three separate processing systems. One system appears to process information mainly about shape; a second, mainly about color; and a third, movement, location, and spatial organization.

Human psychological studies support the findings obtained through animal research. These studies show that the perception of movement, depth, perspective, the relative size of objects, the relative movement of objects, shading, and gradations in texture all depend primarily on contrasts in light intensity rather than on color.

Perception requires various elements to be organized so that related ones are grouped together. This stems from the brain’s ability to group the parts of an image together and also to separate images from one another and from their individual backgrounds.

How do all these systems combine to produce the vivid images of solid objects that we perceive? The brain extracts biologically relevant information at each stage and associates firing patterns of neuronal populations with past experience.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org