What Can Animals Sense That We Can't?

- Published31 Jul 2017

- Reviewed31 Jul 2017

- Author Alexis Wnuk

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

A lot, it turns out. Some animals can detect forms of energy invisible to us, like magnetic and electrical fields. Others see light and hear sounds well outside the range of human perception.

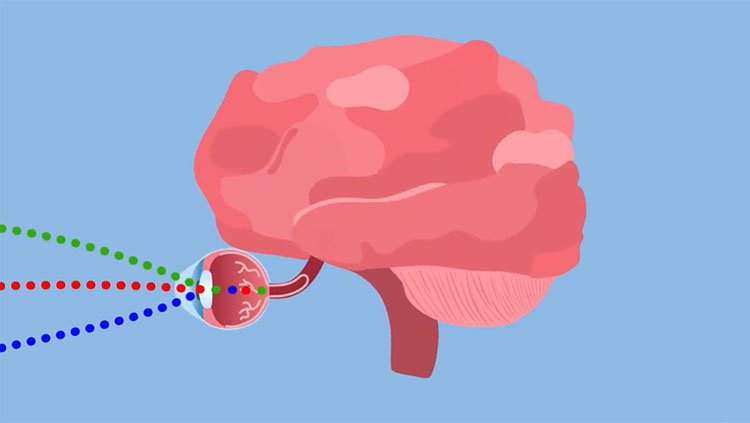

Scientists believe a light-detecting protein in the eye called cryptochrome functions as a magnetic field sensor. This same protein is involved in our own circadian rhythms, and some researchers have started wondering whether humans also have a magnetic sense.

Sharks – as well as skates and rays – detect electric fields using a network of organs called ampullae of Lorenzini. Embedded in the skin around the head, each of these structures is made up of a jelly-filled pore leading to a bundle of electrical sensors.

Large pores located between the eyes and nostrils contain sensory nerve fibers that pass information to the brain’s visual processing center. Heat activates the sensory cells by opening a specific type of ion channel — small proteins in the cell membrane that permit charged particles to flow into or out of the cell. These channels are called TRPA1 ion channels, but in humans, they’re better known as “wasabi receptors” because they’re activated by the pungent compounds found in wasabi and horseradish.

The snowy Arctic reflects a lot of UV light. Reindeer can easily spot their preferred snack, lichens, because lichens trap UV light and pop out against the highly-reflective snow. It turns out that wolves’ fur also absorbs UV light, making it easier for reindeer to steer clear of their natural predator.

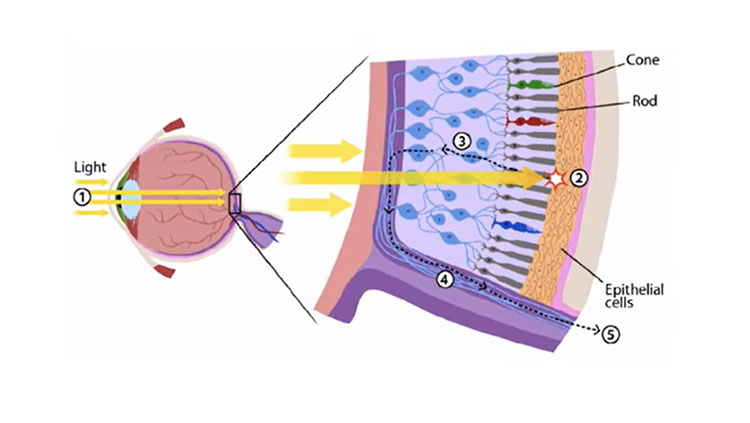

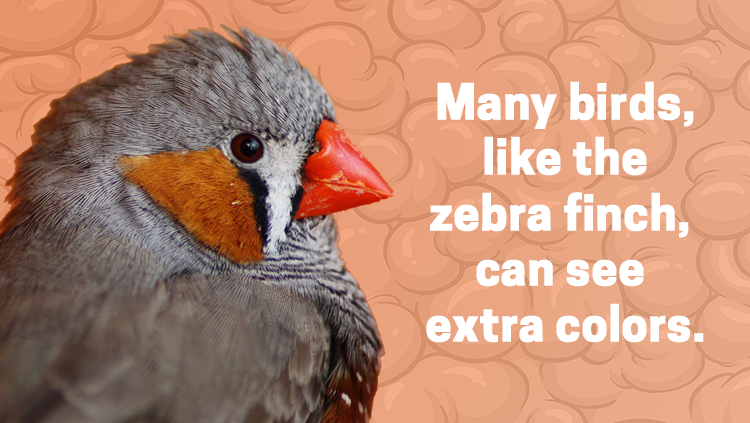

These animals are tetrachromatic, meaning their retinas possess four different types of color-sensing cones. Humans possess only three, except in rare cases of tetrachromacy, a genetic mutation where a person possesses four types of cone cells in the eye, allowing them to perceive more colors.

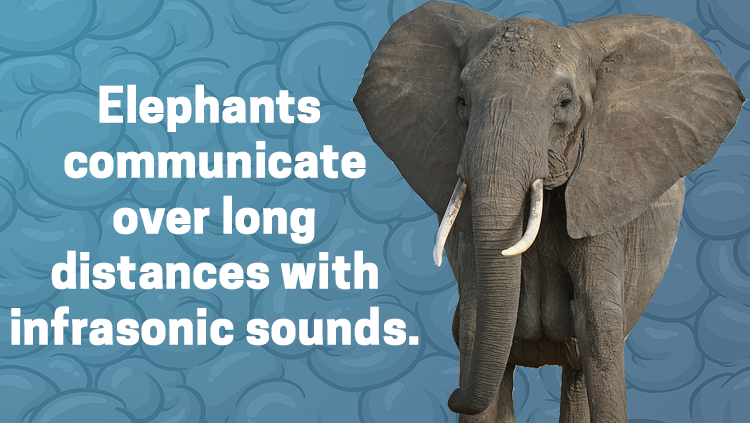

Infrasonic refers to sounds below 20 Hz, the threshold of normal human hearing. African elephants generate low-frequency calls to communicate with potential mates up to 6 miles away.

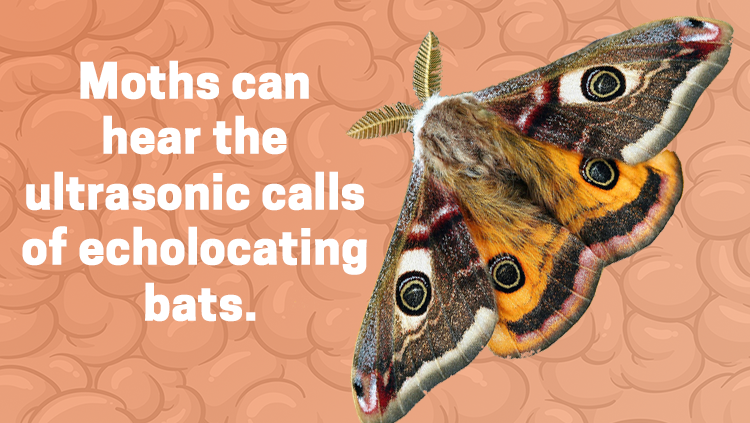

Ultrasonic sounds are above 20,000 Hz, the upper limit of human hearing. Bats generate ultrasonic calls and judge how long it takes for the echoes to return to create a mental map of their environment and find their next meal. Moths might have evolved exquisitely-sensitive hearing to dodge these predators. The greater wax moth has the most sensitive high-frequency hearing in the animal kingdom, registering frequencies in the ballpark of 300,000 Hz.

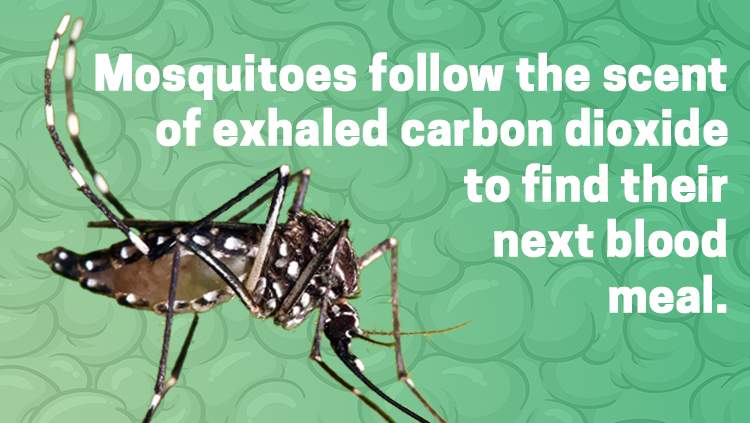

Their maxillary palps – small, antennae-like sensory organs – contain special receptors for carbon dioxide.

Images by Michael Richardson

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org