Struggling to Speak: The Brain Map of Patient Tan

- Published29 Jun 2016

- Reviewed29 Jun 2016

- Author Jessica P. Johnson

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

In 1861, the physician Pierre-Paul Broca met a man who suffered from a puzzling condition – he could only say the word “Tan.” When Patient Tan, as the man came to be know, passed away, Broca’s study of his brain revealed the cause of this deficit, and revealed much about the mechanisms behind human language.

To learn more, listen to this podcast from BrainFacts.org.

Have a question about what you just heard in our Podcast? Submit Your Question

Music by Josh Woodward, used under a creative commons license.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

SfN: I'm Jessica Johnson, reporting for BrainFacts.org.

In 1861, a French physician named Pierre-Paul Broca met a 51-year-old man who was lying on his deathbed in a hospital for the mentally ill. Louis Victor Leborgne, who had come to the hospital 21 years earlier, was paralyzed on the right side of his body, suffered from advancing gangrene, and could only speak a single syllable – “tan.” Fellow patients and doctors referred to Leborgne as Patient Tan.

Leborgne died a few days after meeting Broca, but not before giving his permission for the hospital to perform an autopsy. While examining Leborgne’s brain, Broca discovered a mysterious lesion in the left frontal lobe and wondered whether this was the cause of Leborgne’s speech deficit. A few months later, Broca met another of the hospital’s residents – Lazare Lelong – who experienced similar speech deficits. After Lelong’s death, Broca again found a lesion in the same region of the brain.

Nina Dronkers: Broca’s theory was that this part of the frontal lobe – the lower part of the frontal lobe of the brain – was responsible for what we now call speech production.

I'm Nina Dronkers. I'm the director of the Center for Aphasia and Related Disorders with the V.A. Northern California Health Care System in Martinez, California.

SfN: As Broca and other physicians found more patients with these brain lesions, their speech deficits became known as Broca’s Aphasia, and the affected region of the brain, Broca’s Area. Speech deficits usually appeared very suddenly as the result of stroke or other brain trauma, and individuals were left with a limited vocabulary often consisting of repeated words or nonsense syllables.

Dronkers: We have a patient who used to say, “tono tono tono tono tono,” over and over again. We have patients who say, “yes yes” or “dubbadoowa dubbadoowa.” I had one who said, “sweet sweetie. I miss sweet sweetie.”

SfN: Individuals with aphasia are usually aware of their speech deficits, but damage to their speech centers also impairs their written language and even sign language abilities. So they must resort to using less defined communication tools to compensate.

Dronkers: The same utterances would be produced, but they would vary those expressions. Meaning using their facial expressions to indicate whether it's a question or a statement or surprise or anger. They would use changes in their intonation. “Tono tono?” would mean a question, versus “tono tono tono” would mean a statement. Of course the interpretation depends on the listeners. But you certainly can have a conversation with someone who has severely reduced speech like that.

SfN: Broca was not the first physician to toy with the idea that different brain regions handle different functions, but Dronkers says his careful documentation of individuals with Broca’s Aphasia provided the evidence that was needed to convince the skeptics.

Dronkers: These two cases helped Broca to really launch the idea that there are brain regions that can support specific kinds of functions like language and cognition. Things that really make us tick as humans. And with this good documentation we’re able to understand that a brain injury to a specific area of the brain can cause a specific deficit.

SfN: Over the past 150 years, Dronkers and others have worked to build upon and refine Broca’s theories. In 2007, Dronkers and several French colleagues gained permission to perform high resolution MRI scans of Leborgne’s and Lelong’s brains to pinpoint the brain regions that caused their symptoms. It was the first such scan to be performed on Lelong’s brain. The scans showed that Leborgne’s and Lelong’s lesions were in slightly different regions of Broca’s Area, possibly explaining the variations in their speech abilities.

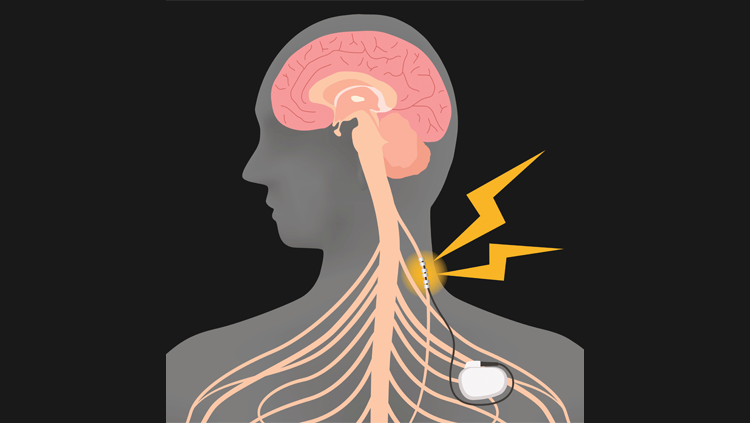

Dronkers: But what was really exciting was that we also found a common area of injury in both cases that didn't involve the frontal lobe, per se. It involved the fiber pathways that connect the frontal lobe to the language areas in the back of the brain. So the language information that we might be thinking about in the backs of our brains can't get through to the front part of the brain that helps us to articulate it. It's like a bridge between the two areas and in the case of both Leborgne and Lelong that bridge was broken. That's really what we think is going on in the cases of these patients who have these recurring utterances.

SfN: Leborgne and Lelong suffered permanent speech deficits because their brain lesions damaged both Broca’s Area and their fiber pathways. However, some individuals with aphasia may eventually regain speech abilities. When damage is restricted to Broca’s Area, speech may return in 3 to 6 weeks with therapy with a speech-language pathologist. It’s a much longer wait when damage is restricted to the fiber pathways, but there is still hope if the brain’s speech and language comprehension centers are undamaged.

Dronkers: We have learned that if that fiber bundle is affected, the brain – clever thing that it is – the brain figures out that there are other ways of connecting up.

SfN: Dronkers credits Broca’s work as the inspiration behind several modern branches of neuroscience including neuropsychology, neurolinguistics, and cognitive neuroscience. But she also credits the research participants.

Dronkers: If you have a brain injury, that's a pretty darned difficult thing to cope with. And the people like that take their time to help us learn from them -- that's huge. We couldn't do it without them.

Thanks for listening. Check out more information about how the brain produces speech and processes language at BrainFacts.org.