Scientists Are Getting Closer to Understanding How COVID-19 Triggers Long COVID

- Published7 Jan 2026

- Author Fred Schwaller

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Millions of people with long COVID grapple with extreme tiredness, shortness of breath, body pain, weakness, and brain fog. This debilitating chronic condition impacts their ability to work, study, and perform daily activities requiring physical strength or focus. Reliable data is limited, but some estimates say 400 million people worldwide have had or still live with the condition.

Physicians focus on managing their patient’s long COVID symptoms with antiviral medication, physical therapy, and talk therapy. Therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can reduce fatigue and stress symptoms in people with long COVID, but they don’t address the root biological causes of the disease. The challenge in treating long COVID comes from the fact that scientists are still working to understand its underlying causes, said Dena Zeraatkar, a public health expert at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

“The pathophysiology of long COVID is uncertain right now,” said Zeraatkar. “No hypotheses about the causes account for the full diversity of symptoms. Therefore, treating long COVID is very difficult.”

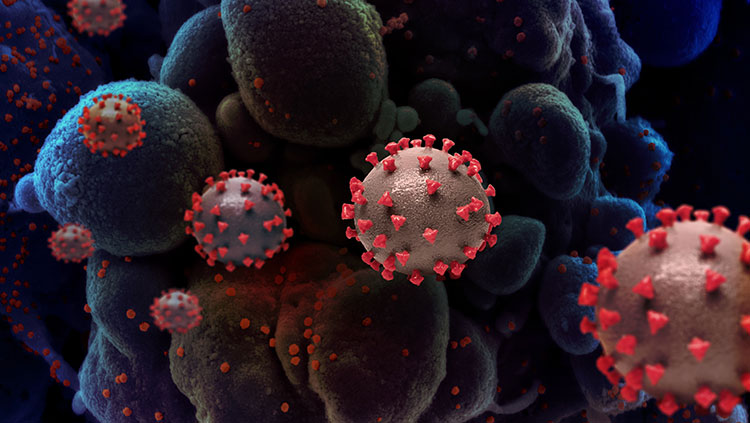

However, scientists are seeing signs of how the virus that causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) damages the nervous system, and many of them are pointing to inflammation. The first clues came in 2020 when researchers found fragments of SARS-CoV-2 inside people’s brains and nervous systems after severe COVID infection. More recent studies show pieces of the virus can remain in the brain for up to four years after infection. The virus also lingers in the tissues surrounding the brain — in the skull, blood vessels, and in membranes called meninges that wrap the brain like a bag.

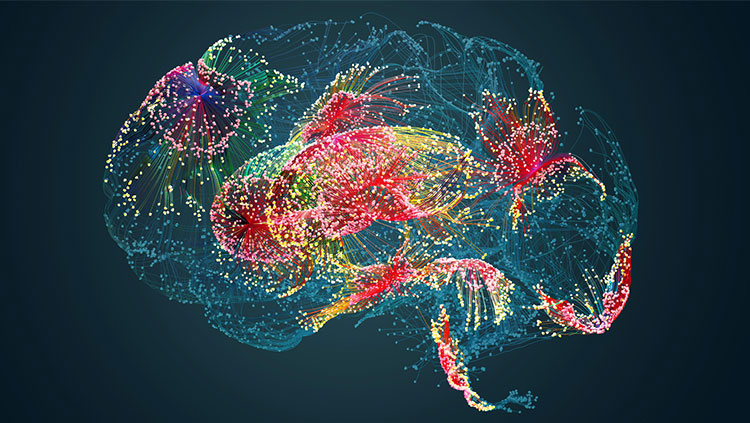

“Now we know the causes involve many effects of the virus on the brain: oxygen deprivation (hypoxia), damage of brain vasculature, immune system [changes], and even broader psychological and social stressors related to the pandemic,” said Luana da Silva Chagas, a neurobiologist at Fluminense Federal University, Brazil, mentioning her review co-authored with Claudio Alberto Serfaty. Chagas noted the virus can cause some of the brain’s immune cells, called microglia, to excessively prune synapses and alter brain structure. This over-trimming reflects dysfunction in neuroplasticity — the brain’s ability to modify its connections — which may contribute to the neurological and cognitive symptoms observed in long COVID.

Still, scientists don’t fully know if SARS-CoV-2 can get past the blood-brain barrier (BBB) — the protective, cell-packed membrane lining blood vessels in the brain. “We think that maybe it just damages the brain’s blood vessels without actually getting into the brain, but it’s still an open question,” said Matthew Campbell, a neuroscientist at Trinity College Dublin.

A study published in 2024 found brain fog is associated with disruptions of the BBB in patients with long COVID. “We discovered that the network of blood vessels that supply the brain were becoming ‘leaky’ in patients with long COVID who were reporting brain fog,” said Campbell, who led the study.

“We believe the leaky blood vessels prime the brain for damage. Unwanted material from the blood can access the brain and cause havoc with neuronal function,” Campbell added.

Finding the Root Cause

Long COVID is not unique. Brain fog — defined as confusion, memory, and concentration challenges following an infection — is also a feature of chemotherapy treatments and post-viral fatigue. Research on Ebola revealed neurological symptoms could be linked with inflammation in the brain. This knowledge led COVID researchers to question whether inflammation might also play a role in long COVID.

The first evidence came in 2021 when a study of long COVID patients found inflammatory cytokines in their brains. As potent signaling molecules, cytokines can activate or suppress the immune system. They help the body fight off attackers by inducing inflammation.

The study concluded immune-related inflammation may be the driving force behind long COVID symptoms. The debilitating effects of long COVID and brain fog, the authors speculated, arise when inflammation is still triggered long after the immune system defeats the infection.

Findings in a 2025 study showed how COVID-19 infection causes microglia to become dysfunctional and start damaging neurological tissue. The authors analyzed autopsy data from people who had died from COVID-19 infection. They found inflammation in pockets of people’s brains caused by immune cells damaging blood vessels, notably in brainstem regions crucial for regulating bodily functions like heart rate and breathing.

“A key study in 2022 also found structural changes in brain regions related to memory, anxiety, and smell, and, importantly, were observed even in individuals who had only mild cases of COVID-19,” said Chagas.

Inflammation is seen as a major driver of long COVID in other organs, too. In the lungs, for example, inflammation prevents the lung tissue from repairing itself, causing symptoms like breathlessness and fatigue.

Testing for New Treatments

Existing research has paved the way for the first clinical trials testing medicines to treat long COVID. But while scientists are still developing new treatments, the good news is that we already know how to prevent long COVID. Vaccines have worked wonders by preventing COVID-19 infections from spreading, reducing the severity of symptoms, and reducing risk of developing long COVID. In 2020, 10% of people with COVID-19 infections were estimated to develop long COVID. This number dropped to 3.5% among vaccinated people in 2024.

But 3.5% of vaccinated people, along with those who are unvaccinated, still represent a huge number of people with long COVID who can’t get treatment.

Progress in understanding long COVID has helped to find new potential treatments. Right now, “hundreds” of therapies are under investigation to treat the neurological damage and cognitive impairments associated with long COVID, said Zeraatkar.

In 2024, Zeraatkar published a systematic review of all the studies published to date on interventions to treat long COVID. These interventions included medications, doctor-prescribed exercise programs, cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), and dietary interventions.

Clinical trials are underway to test whether anti-inflammatory drugs are effective and safe options for treating the neurocognitive symptoms of long COVID. These include new drugs like Bezisterim and Toxilizumab, which work by reducing inflammatory molecules in the brain. Other trials are testing Upadactinib and Pirfenidone, which are already approved for use in other diseases — meaning the drugs would likely receive regulatory approval for long COVID much quicker, if proven effective and safe.

If successful, Campbell says these trials could also help treat other neurological conditions where brain fog is a feature.

“Understanding the causes of long COVID will help us to understand a range of other neurological conditions,” he said. “So really, this is just the beginning of a very long road ahead of scientific discovery.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Al-Aly, Z., Davis, H., McCorkell, L., Soares, L., Wulf-Hanson, S., Iwasaki, A., & Topol, E. J. (2024). Long COVID science, research and policy. Nature Medicine, 30(8), 2148–2164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

Billioux, B. J., Smith, B., & Nath, A. (2016). Neurological complications of Ebola virus infection. Neurotherapeutics, 13(3), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-016-0457-z

Da Silva Chagas, L., & Serfaty, C. A. (2024). The influence of Microglia on Neuroplasticity and Long-Term Cognitive Sequelae in Long COVID: Impacts on brain development and beyond. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(7), 3819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25073819

Darley, D. R., Dore, G. J., Cysique, L., Wilhelm, K. A., Andresen, D., Tonga, K., Stone, E., Byrne, A., Plit, M., Masters, J., Tang, H., Brew, B., Cunningham, P., Kelleher, A., & Matthews, G. V. (2021). Persistent symptoms up to four months after community and hospital‐managed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The Medical Journal of Australia, 214(6), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50963

Douaud, G., Lee, S., Alfaro-Almagro, F., Arthofer, C., Wang, C., McCarthy, P., Lange, F., Andersson, J. L. R., Griffanti, L., Duff, E., Jbabdi, S., Taschler, B., Keating, P., Winkler, A. M., Collins, R., Matthews, P. M., Allen, N., Miller, K. L., Nichols, T. E., & Smith, S. M. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature, 604(7907), 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5

Fekete, R., Simats, A., Bíró, E., Pósfai, B., Cserép, C., Schwarcz, A. D., Szabadits, E., Környei, Z., Tóth, K., Fichó, E., Szalma, J., Vida, S., Kellermayer, A., Dávid, C., Acsády, L., Kontra, L., Silvestre-Roig, C., Moldvay, J., Fillinger, J., . . . Dénes, Á. (2025). Microglia dysfunction, neurovascular inflammation and focal neuropathologies are linked to IL-1- and IL-6-related systemic inflammation in COVID-19. Nature Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-01871-z

Greene, C., Connolly, R., Brennan, D., Laffan, A., O’Keeffe, E., Zaporojan, L., O’Callaghan, J., Thomson, B., Connolly, E., Argue, R., Meaney, J. F. M., Martin-Loeches, I., Long, A., Cheallaigh, C. N., Conlon, N., Doherty, C. P., & Campbell, M. (2024). Blood–brain barrier disruption and sustained systemic inflammation in individuals with long COVID-associated cognitive impairment. Nature Neuroscience, 27(3), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01576-9

MacEwan, S. R., Rahurkar, S., Tarver, W. L., Eiterman, L. P., Melnyk, H., Olvera, R. G., Eramo, J. L., Teuschler, L., Gaughan, A. A., Rush, L. J., Stanwick, S., Burpee, S. B., McConnell, E., Schamess, A., & McAlearney, A. S. (2024). The Impact of Long COVID on Employment and Well-Being: A Qualitative Study of patient Perspectives. Journal of General Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-09062-5

Radke, J., Meinhardt, J., Aschman, T., Chua, R. L., Farztdinov, V., Lukassen, S., Ten, F. W., Friebel, E., Ishaque, N., Franz, J., Huhle, V. H., Mothes, R., Peters, K., Thomas, C., Schneeberger, S., Schumann, E., Kawelke, L., Jünger, J., Horst, V., . . . Radbruch, H. (2024). Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling of brainstem, cerebellum and olfactory tissues in early- and late-phase COVID-19. Nature Neuroscience, 27(3), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01573-y

Rong, Z., Mai, H., Ebert, G., Kapoor, S., Puelles, V. G., Czogalla, J., Hu, S., Su, J., Prtvar, D., Singh, I., Schädler, J., Delbridge, C., Steinke, H., Frenzel, H., Schmidt, K., Braun, C., Bruch, G., Ruf, V., Ali, M., . . . Ertürk, A. (2024). Persistence of spike protein at the skull-meninges-brain axis may contribute to the neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Cell Host & Microbe, 32(12), 2112-2130.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2024.11.007

Sariol, A., & Perlman, S. (2025). Lung inflammation drives Long Covid. Science, 387(6738), 1039–1040. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adw0091

Xie, Y., Choi, T., & Al-Aly, Z. (2024). Postacute sequelae of SARS-COV-2 infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron eras. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(6), 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2403211

Zeraatkar, D., Ling, M., Kirsh, S., Jassal, T., Shahab, M., Movahed, H., Talukdar, J. R., Walch, A., Chakraborty, S., Turner, T., Turkstra, L., McIntyre, R. S., Izcovich, A., Mbuagbaw, L., Agoritsas, T., Flottorp, S. A., Garner, P., Pitre, T., Couban, R. J., & Busse, J. W. (2024). Interventions for the management of long covid (post-covid condition): living systematic review. BMJ, e081318. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2024-081318

What to Read Next

Also In COVID-19

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org