Phantom Phone Signals Show How Smartphones Shape Our Perception

- Published3 Apr 2024

- Author Dina Radtke

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Before the smartphone era, medical staff relied on the buzzing and dinging of their pagers for critical patient communications. So keyed into the demands of their devices, many doctors and nurses swore their pagers vibrated or dinged even when they weren’t being paged.

But the pagers had been silent and still. Those doctors and nurses experienced a misperception, or phantom signal. In a world where smartphones, and their notifications, are ubiquitous, the experience of phantom phone signals is increasingly common. And, while some researchers have posited phantom vibrations — the most common smartphone-related misperception — stem from imprecise skin sensors, research is pointing to lifestyle factors. Turns out stress and excessive smartphone use may be hijacking normal perception processes.

“Our brains do not have the neural resources to process every piece of sensory information in our environment,” says Susana Martinez-Conde, a neuroscientist specializing in ophthalmology and neurology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University. We select the information most important to us and “do a whole lot of guesstimating” to fill in the rest.

Even under the best of circumstances your perception can never fully match reality. When you look at your phone, your visual cortex identifies the outline of a rectangle. Before your brain can fully process the rest, it uses past knowledge to predict an image and display it before your eyes. This process typically works quite well, but under certain conditions, your brain's prediction system shows you something that’s not there. Your phone illuminates in the corner of your eye, but it’s a black screen when you turn to glance at it.

Working as a health professional creates all the right circumstances for misperception: making critical decisions regarding patients while managing a heavy and often urgent workload. Such high-stress environments can alter neural processing and give rise to illusory experiences.

A 2013 study published in the Public Library of Science (PLOS) showed that at the beginning of a medical internship, 78.1% of the new doctors experienced phantom vibration and 27.4% experienced phantom ringing. Three months into the internship, 95.9% had experienced phantom vibration and 84.9% experienced phantom ringing.

This spike in smartphone-related misperceptions correlated with higher stress and increased anxiety and depression scores. Martinez-Conde says that in a heightened state of arousal, the brain becomes hypersensitive and hyperreactive. The medical interns learned to associate their phone alerts with critical information, so their brains actively predicted and prepared for an incoming call.

A constant bombardment of phone notifications primes your brain to search for them in their absence.

Hallucinatory-like experiences (HLEs), like hearing your name called or vivid daydreaming, affect 5-10% of the population, but somewhere between 27-89% experience phantom phone signals. A November 2022 paper published in Psychiatry Research comparing the two found the greatest predictors of HLEs are top-down influences — such as attentional dysfunction or expectations about a situation — and mental health disorders like anxiety and depression. These factors affect phantom phone signal experiences, but excessive smartphone use was the strongest predictor.

This is because our brains rely heavily on past experiences to make predictions. A constant bombardment of phone notifications primes your brain to search for them in their absence. They are cues we have learned to respond to immediately, like how you react strongly to someone calling your name.

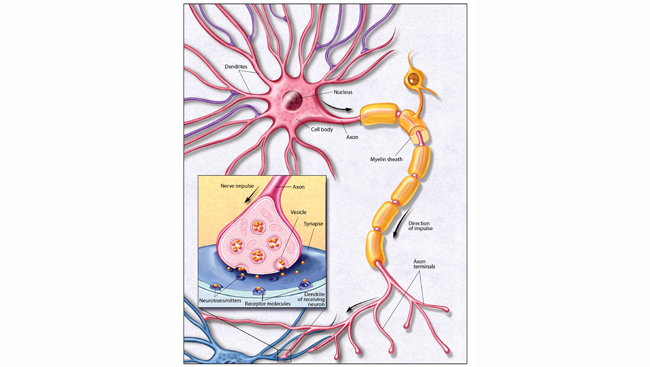

Reward learning influences our prediction systems. A phone notification — whether it signals activity on your social media post or a new match on a dating app — has come to symbolize an impending reward, which can be something pleasurable or just something important (like a page that your patient is going into labor). In expectation of a reward, neurons release dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with motivation and alertness (among other functions). When the reward is greater than expected, dopamine signaling increases — a text from a crush might feel more exciting than a text from your mom. Dopamine signaling decreases when the reward is less than expected, like when you think you received a text only to find you did not.

The possibility of an important text coming through keeps your brain searching for its signal — so much so, Americans check their phones on average 144 times per day, according to a survey of 1,000 adults by Reviews.org.

Repeatedly checking your phone is associated with activation in subcortical areas involved in emotion regulation and the prefrontal cortex, a region involved in attentional and cognitive control, says Johanna Seitz-Holland — a neuroscientist studying the neural correlates of psychiatric disorders at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “Functional connectivity — how these areas communicate with each other — may be influenced by social media use,” she says, and impaired communication between these brain regions increases the risk of developing a psychiatric disorder.

Seitz-Holland noted the prefrontal cortex is not fully developed until later in life, and increased screen time in adolescence could affect the proper development of this region. This may be why increased social media use is associated with maladaptive behaviors like binge eating or disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Researchers are still working to determine whether the culprit is screen time itself or if screen time is replacing healthy and stress-reducing lifestyle choices like face-to-face social interactions and spending time outdoors.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Aleksandrowicz, A., Kowalski, J., & Gawęda, Ł. (2023). Phantom phone signals and other hallucinatory-like experiences: Investigation of similarities and differences. Psychiatry Research, 319, 114964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114964

Kruger, D. J., & Djerf, J. M. (2016). High Ringxiety: Attachment Anxiety Predicts Experiences of Phantom Cell Phone Ringing. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 19(1), 56–59. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0406

Lin, Y. H., Lin, S. H., Li, P., Huang, W. L., & Chen, C. Y. (2013). Prevalent hallucinations during medical internships: phantom vibration and ringing syndromes. PloS One, 8(6), e65152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065152

Lin, Y. H., Lin, K. I., Pan, Y. C., & Lin, S. H. (2020). Investigation of the Role of Anxiety and Depression on the Formation of Phantom Vibration and Ringing Syndrome Caused by Working Stress during Medical Internship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207480

Pisano, S., Muratori, P., Senese, V. P., Gorga, C., Siciliano, M., Carotenuto, M., Iuliano, R., Bravaccio, C., Signoriello, S., Gritti, A., Pascotto, A., & Catone, G. (2019). Phantom Phone Signals in youths: Prevalence, correlates and relation to psychopathology. PloS One, 14(1), e0210095. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210095

Wagner, Jeff. (2023). “Why do we feel phantom vibrations from our phones?” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/minnesota/news/why-do-we-feel-phantom-vibrations-from-our-phones/. Accessed 13 March 2024.