New Tech Offers Glimpse Into Future of BCIs

- Published17 Dec 2025

- Author Bella Isaacs-Thomas

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Amputations or brain and spinal cord injuries limit how people can engage with the world around them. Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) link the body with technologies like bionic limbs that can empower users to connect with their environments in new ways.

An ever-evolving landscape, researchers continually develop novel BCI devices and build on the capabilities of existing ones. On Nov. 17 in San Diego at Neuroscience 2025, the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting, scientists shared new data underscoring the safety profile of one device. They also introduced an emerging technology that could eventually add to the suite of tools available to BCI developers.

No two amputations or injuries are exactly alike. But the field’s ultimate goal is to scale up these devices to be made commercially available for users. Small-scale studies involving patients and academic researchers lay the groundwork for companies to eventually run larger trials and for regulators to ultimately clear them for the market, said Robert Gaunt, a panelist and associate professor in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Pittsburgh.

“We're motivated to actually try and produce devices that are going to be useful for people to improve their quality of life. And if these things stay in academic labs, we'll never achieve that,” Gaunt said. “Companies will need to do this work. But my opinion is that the companies will never get there unless this kind of work happens first.”

Using Tiny Magnets to Improve Movement

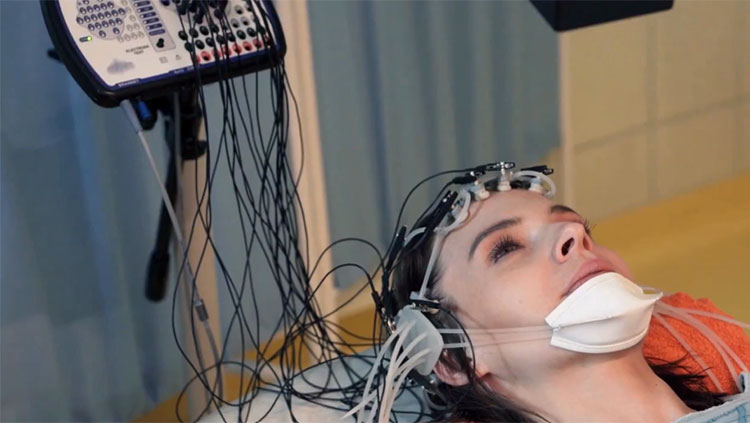

BCIs are powered by cues from the body, like brain activity. Capturing this information is a challenge. Electronic sensors can be placed on the skin or the skull, but this indirect measurement can yield muddled data. Some devices require an implant directly into the body, which improves signal quality but requires invasive surgery.

Christopher Shallal, a graduate researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, presented preliminary research on magnetomicrometry, a new technology designed to power prosthetic limbs. This approach is not technically a BCI because it doesn’t directly involve the brain. Instead, it uses sesame seed-sized magnetic beads implanted into the muscle to capture signals.

“We’ve learned that tiny magnetic beads unlock a wealth of muscle information suggesting the possibility for intuitive prosthetic control, and we hope to introduce this as a new way to interface with the human body,” Shallal said.

After evaluating the beads in turkeys, Shallal’s team has now successfully implanted them in three patients with below-the-knee amputations who use these tiny magnets, plus an external array of sensors, to control a bionic ankle joint. This clinical study is their first to involve humans, and Shallal said the participants have not experienced complications related to the beads for up to a year following implantation.

“It certainly looks encouraging as either an alternative or supplementary approach to classical EMG recordings for control of prostheses,” said Gregory Clark, professor emeritus in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Utah, who wasn’t involved with the research.

A Decade of Safety Data

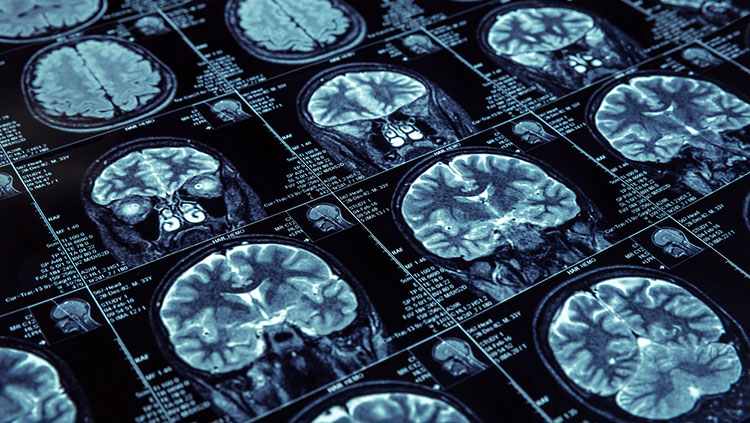

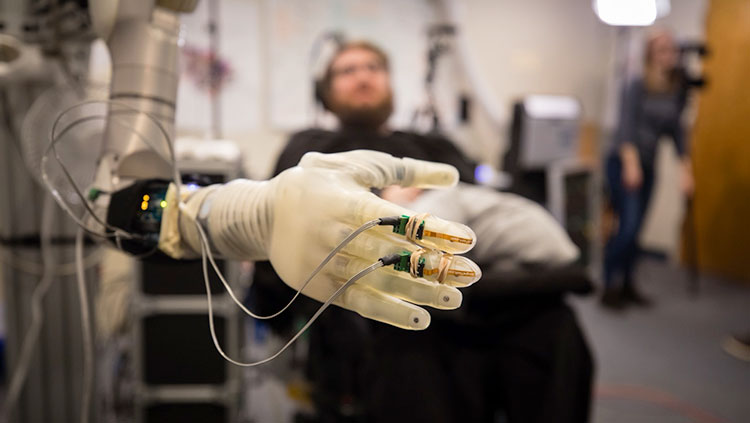

People with spinal cord injuries often lose the ability to move their bodies below the site of their injury. BCIs can help restore movement by using electrode arrays implanted in the motor cortex to record activity and power the movement of a robotic arm. Gaunt emphasized, however, that motion isn’t the whole story — the ability to feel the external world is also key to meaningful and effective engagement.

“What we also want to be able to do now is take information from a robotic limb — say, touch sensors on a robot — and put this back into the brain to restore the sense of touch,” Gaunt said, adding his team achieves this goal using electrical microstimulation in patients’ somatosensory cortex, a brain region responsible for processing sensory information across the body. When they receive this stimulation, users can more quickly and efficiently move objects using a robotic limb.

Gaunt was referring to a specific implant called the Blackrock NeuroPort electrode array. His team’s study assessed its use in five people, including one who received the implant a decade ago. Over the years, the locations where people feel sensations in their own hands from the brain stimulation have remained consistent. The device itself hasn’t affected activity beyond these sensory functions, and unintentional, persistent sensations occur rarely.

This aggregation of safety data, which has not yet been peer reviewed, aims to demonstrate “long-term microstimulation in the brain to restore this sense of touch is safe and effective,” Gaunt said.

The importance of touch is hard to overstate — Clark noted we use the same term to refer to our emotions. Being able to feel and realistically move a prosthetic hand, he said, is the difference between the hand feeling like a tool or a truly “embodied” new part of a user’s body.

Safety data is key to moving BCI devices forward. Although it lacks the pizazz of splashier studies detailing novel technologies, Clark said this one is “is incredibly important because if it ain't safe, it ain't going to be used.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Gaunt, R. A., Greenspon, C. M., Hobbs, T., Verbaarschot, C., Alamiri, A., Schelchova, N., Lienkamer, R., Ye, J., Satzer, D., Valle, G., Miller, L. E., Hatsopoulos, G., Downey, J.E., Boninger, M., Collinger, J. L. (2025) Ten-year safety profile of intracortical microstimulation in the human somatosensory cortex. [Poster Abstract]. University of Pittsburgh; University of Chicago; Carnegie Mellon University; Chalmers University of Technolgy, Gothenburg. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, United States. Program No. NANO022.10. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/21171/presentation/32133

Shallal, C., Herrera-Arcos, G., Herr, H. (2025) Implanted magnets enable wireless muscle state sensing for neuroprosthetic control applications. [Poster Abstract]. MIT, Cambridge, MA. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, United States. Program No. PSTR457.13. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/21171/presentation/32462

Also In Tools & Techniques

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

.jpg)