Ever wondered how you instinctively know which way is home, even at night or in fog when you can't see a thing?

This video explores the secrets of path integration, or how the brain develops its internal navigation system. See how the brain continuously monitors our movements to create "homing vectors," helping guide us back home. Learn how these small calculations build into intricate cognitive maps of the world around us — followed by what happens when they go wrong.

This is a video from the 2025 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Samuel Shaw

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

In the British countryside, things look a little samey. And somehow, in conditions as misty as this,

I will still find my way home. So what is this process, and how can it create entire maps of the

world inside our head?

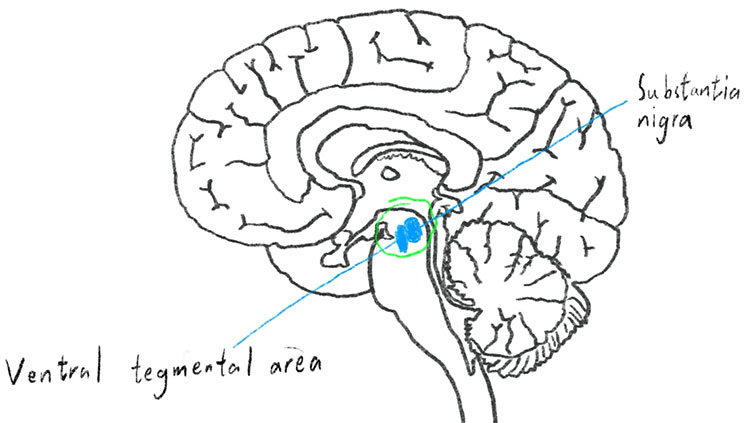

The answer lies in what we call path integration. It's essentially an internal mechanism that keeps track of your location and which way is home. Right now, I'm in a random field, but my brain has been keeping track of how far I've left from home by monitoring things like what muscles I used and how much I've used them, as well as the direction that I've traveled by monitoring things like rotation.

Let's take a look at how this information is used to find our way home. Whilst I don't usually live in a field, let's imagine this point here is my home. As I'm exploring the area, I make different movements. Let's call this first one M1, the second one M2, and the last one M3.

By using the movement information our brain has been monitoring, it can calculate what's called a homing vector — essentially, the way home. And this is our path integrator. This is done by taking away each of the movements I've made. In this case, being home, or H, is equivalent to taking away M1, M2, and also M3.

Now I know what you're thinking: This sounds great, but it's only telling me how I can get home. Well, initially, this was thought to be the only purpose of path integration.

However, Wang proposed that this mechanism may actually be able to represent highly-complex information about our environments and store it in our brain and allow us to use flexible navigation. This is known as a cognitive map.

Wang proposed that these cognitive maps can be created in three steps.

[Step 1: Spatial Updating] If the basic path integration discussed earlier can be used to create home vectors, then can't the same system be used to create vectors for other points of interest?

Let's take a look at how this may occur. Imagine, whilst I explore the environment, I come across a food source. Whilst here, my brain has already calculated the homing vector by subtracting the first movement, like in the example before.

As I continue to explore, unsurprisingly, I'll still want to remember where I found that food for the future. As such, a new path integrator is made for food, calculated as a vector like with my home. Eventually, I find water, and this will have its own path integrator, too.

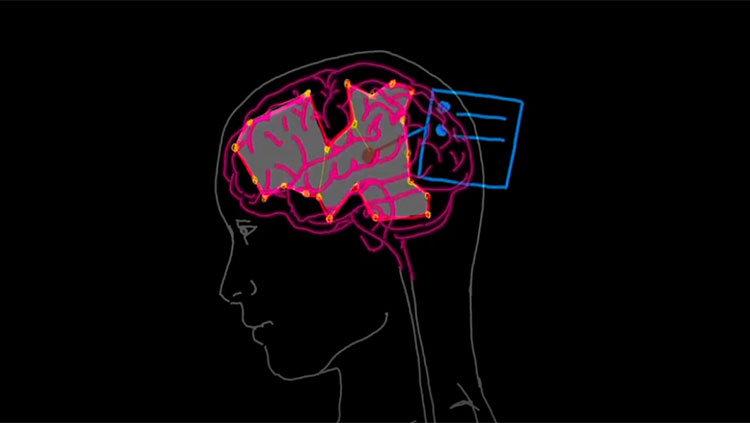

Over time, I continue to explore, creating new path integrators for points of interest, each independently updating their vector. This collection of vectors can create a dynamic map of the environment, and this is known as the spatial updating system.

[Step 2: Long-term Memory (And Getting Lost)] These vectors are theorized to be copied into our long-term memory for storage. This can be thought of as a static save file of the various path integrators that can be reloaded in the future when navigating the same environment.

Alternatively, when we can see multiple points of interest together, this can create another representation in our long-term memory. One of the big criticisms of path integration is that our brain calculates it using internal information, like how far we've traveled. However, this is just an estimate, and it can get this wrong sometimes.

This issue accumulates over time as new vectors are calculated on previous ones. So, the longer your journey, the more errors. And eventually, you'll end up completely lost.

[Step 3: Recalibration] This is where your save files and a process called recalibration come in. This scenario may sound familiar: You're on a walk, but you get lost. You've got no idea where to go.

You walk around, searching for the way home, and all of a sudden, a familiar landmark appears. It's the post from earlier.

When this happens, the save file from your long-term memory is loaded up. Although this save file is from a different location and a specific viewpoint, my save file says I'm only two meters away from the post when I'm really 50 meters away.

This triggers the recalibration process. Your brain is able to use information in your surroundings and subtract all of the incorrect movements or errors from the save file and essentially reset it so that all of your vectors are now facing the right way.

If you're ever feeling lost, just look around. And you might recalibrate and find your way home.

Also In Thinking & Awareness

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org