Can't Picture It: What is Aphantasia?

- Published15 Dec 2025

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

The ability to picture something in our heads may sound like something common to every person. But a small part of the human population is unable to visualize images in their heads.

Explore the neuroscience of aphantasia: the phenomenon of being unable to visualize images in one’s mind. It’s not a medical condition, however, but simply one of many fascinating differences in how people’s brains work.

This is a video from the 2025 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Anthony Bazalaki

Made with Krita and Davinci Resolve

Music by Anthony Bazalaki

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

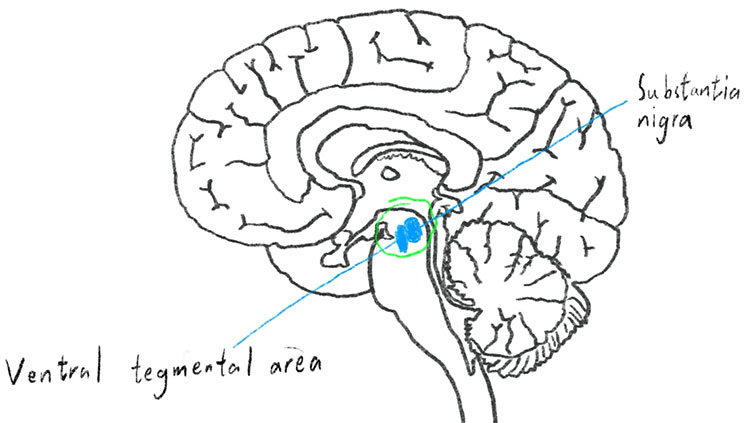

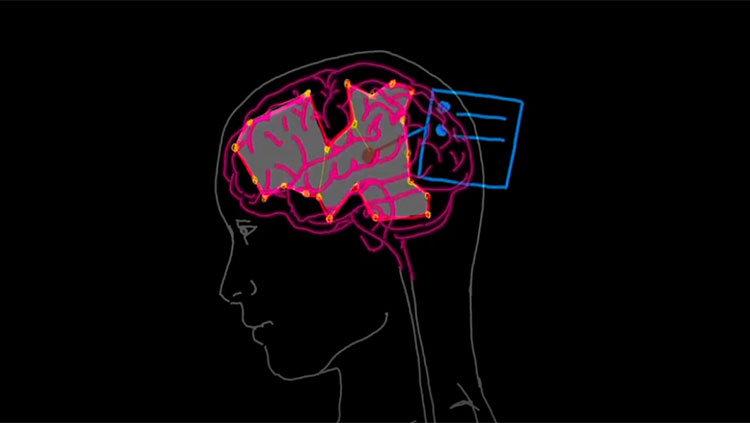

Do me a favor real quick. Close your eyes and imagine a horse. Now tell me: What do you see? Do you see a trusty steed standing still, rearing, or perhaps galloping? Or do you see a vague image of a horse with no color? Or can you see nothing at all? In reality, mental imagery is a spectrum. On one end of the spectrum, the picture in your head can be as vivid as a bright summer's day. On the other end, your mental image can only show up as maybe a dim blur, or even nothing at all. If you were able to visualize that horse fine or better, you are part of 96% of the population. If you are unable to visualize the horse, you belong to the other 4%. This side of the spectrum — the side that has no mental image — is said to have aphantasia. Aphantasia is a new name for an old phenomenon. It was first recognized by Francis Galton in 1880, with him relating someone without a mind's eye — unaware of being blind to mental imagery — to a colorblind man unaware of being blind to color. The condition remained particularly forgotten until it gained public traction following a 2015 study led by Adam Zeman. This study not only recognized and identified aphantasia, but also gave it a name: "a" being a prefix meaning "without," and Ancient Greek "phantasia," meaning "appearance" or "image," together producing "aphantasia." People who have never had a mind's eye usually don't find out until later in life. They usually assume "the mind's eye" is more metaphorical than literal. But how do you even measure how vivid someone's mental imagery is? We usually use a questionnaire. For example: "Rate how vividly you can imagine your friend's face from one to five." The problem with a questionnaire is that it is subjective. Even if two people were to magically have the same mental image, they could report different levels of vividness. There are currently three main ways to measure visual imagery objectively. The first being binocular rivalry. If two different images are shown to both eyes, the brain naturally selects one image to focus on at random. Those without aphantasia are more likely to select one image over the other when told to focus on that specific one, while the brains of those with aphantasia still selectively focus on one image at random. The second way is measuring if your pupils dilate or contract in response to imagining a bright object, or triggering an emotional visual. The third is measuring emotional response to stimuli, such as reading emotional text or viewing a frightening image. Since your body produces sweat when nervous and sweat makes your skin more conductive, measuring skin conductivity is a good way to see if a stimulus provokes an emotional response. Studies in this manner show that aphantasics show much less fear in response to reading a scary story or viewing an evocative image than normal. But how does mental imagery even work? When you see an object with your eyes — a dog, for example — its characteristics, such as being fluffy, four-legged, and cute, are stored by the firing of thousands of neurons in your posterior cortex. The more these neurons fire, the stronger the neuronal connections. And they’re eventually linked into a unique “neuronal ensemble,” one for every object you’ve ever seen. The leading theory is that when multiple of these ensembles fire at the same time, you can imagine countless combinations of scenes, explaining why your imagination seems limitless. It turns out that visualization is a coordination of different regions of the brain to create a seemingly real image in your head. However, we do not know much about the neurological reason for the lack of visualization. People who have lost their sense of mental imagery usually show damage from either the occipital lobe, which processes visual input from eyes, or the parietal lobe, which keeps track of where things are in space. We also know that people who have been born with aphantasia compensate by using areas such as the anterior cingulate cortex, which is responsible for spotting errors. Though there is still much we don’t know about the mind, just because someone can’t visualize doesn’t make them any functionally different than anyone else. Trust me, I’d know…

What to Read Next

Also In Thinking & Awareness

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org